[ad_1]

Ive here. While Russia appears to have concluded that it needs to permanently reposition its economy from Europe and the United States to Asia and the Middle East, economists are only just beginning to grapple with the impact on supply chains. I’m not as sure as these authors are that differences in degree are not differences in kind.

By Tobias Korn, PhD student in economics at Leibniz University Hannover, and Henry Stemmler, postdoc at ETH Zurich.Originally Posted in VoxEU

Russia’s war on Ukraine has halted much of Ukraine’s production capacity. Likewise, the sanctions imposed on Russia by the international community ended decades of economic cooperation across multiple economic sectors. Drawing on empirical evidence from more than 20 years of civil wars around the world, this column informs debates about how international supply chains will adapt to economic disruption from violence and how likely it is that the international economy will return to its predecessors. – war situation.

In addition to the immeasurable personal suffering and severe economic devastation, the devastation wrought on nations by violent war has also brought enormous devastation. Disruption of production sites, disruption of supply chains, and displacement of people often lead to sudden and prolonged disruptions in economic activity. While we don’t have much general empirical evidence for the economic costs of international war, which used to be a rare phenomenon in recent decades, the literature on civil war coined the term “reverse development” to describe the often persistent negative economic Influence ongoing war events (Collier et al. 2003).

Currently, we are seeing this reverse development in Ukraine. Just weeks after Russian troops began their invasion of Ukraine, millions left the country and formerly thriving towns fell to rubble (Skok and de Groot 2022). At the same time, the unprecedented scale of international sanctions against Russia threatens to severely damage the Russian economy and end decades of economic cooperation (Berner et al. 2022, Felbermayr et al. 2019). Nonetheless, despite intense public discussion, an embargo on oil and gas imports from Russia has not been implemented, as several European powers fear the economic consequences of losing these hard-to-replace imports (Bachmann et al., 2022). ). Understanding how the international economy responds to previous disruptions in economic exchanges caused by violent wars helps shape expectations for the economic future of Ukraine, Russia, and sanctioned countries.

(How) can supply chains adapt to economic disruption?

In a recent study, we investigate how international trade flows respond to unilateral economic shocks (Korn and Stemmler 2022). To this end, we focus on national civil wars, which have been found to cause significant disruption to a country’s production and export capabilities (Blattmann and Miguel 2010). Specifically, we ask if and how importers adjust their trade flows if a civil war breaks out in one of their main trading partners (see Arezki 2022 on international spillovers from the Ukraine war). To answer this question empirically, we use bilateral trade data covering the period 1995-2014 for more than 150 countries.

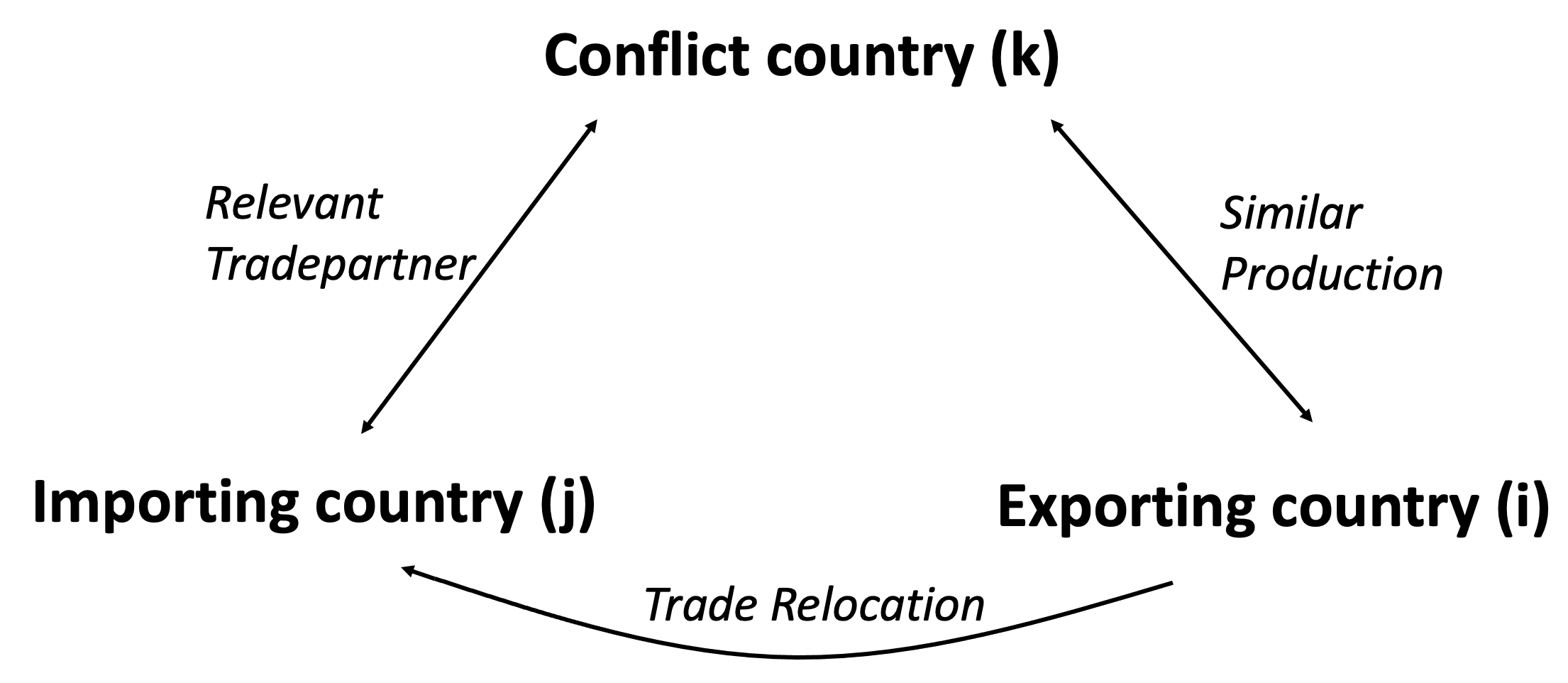

In this dataset, we first identified exporters who experienced civil war in a given year according to the civil war classification of the Uppsala Conflict Data Project (Sundberg and Melander 2013). We then encode the most likely effects of trade diversions out of conflict countries. We encode based on two features, as shown in Figure 1. First, we identified all countries for which the conflict country was once a major trading partner (i.e., the country’s top seven exporters).1 Second, we identified all countries that offer a variety of goods similar to those in conflict countries. Using various classification algorithms, we divided countries into clusters with similar production mixes based on the production of the 61 SITC product lines. We combine these correlation and similarity conditions to code which importer-exporters are likely to be affected by trade relocation as the importing country shifts its demand from the conflicting country to another exporter offering a similar range of goods. Finally, we empirically investigate whether the value of trade between these “relocating pairs” increases due to civil war.

figure 1 Trade Relocation Code Instructions

notes: This figure illustrates our encoding of relocation propensity. For each conflict country k in a given year, we identify its major trading partners and all countries that provide a similar production mix. For each pair ij where the two conditions overlap, ie importer j is a relevant trading partner of conflict country k, and exporter i produces similar products to conflict country k, we expect the trade diversion effect to materialize.

We find strong evidence that global supply chains have adapted relatively quickly to economic disruptions caused by civil wars, but this trade diversion effect exhibits considerable heterogeneity. First, the agricultural supply chain and the mining supply chain responded extremely strongly. On average, trade between such “relocation duos” increased by 12% and 13%, respectively, a year after the Civil War began. In manufacturing, the value of trade grew by an average of 7%, and only if the conflict continued for several years. As a result, manufacturing supply chains appear to be more reluctant to relocate than importing primary commodities. Interestingly, we found no evidence of supply chain adjustments in the fuel industry. If anything, importers will reduce fuel imports from alternative trading partners to maintain their current fuel imports to key export partners currently in conflict. This is the response we are seeing again today, with countries highly dependent on Russian oil and gas working to scale back those imports despite their support of various other sanctions. Our findings further complement the recent discussion in Kwon et al. (2022), they find evidence that sanctioned countries can substitute exports from unsanctioned third countries. If our results apply equally to the economic impact of sanctions, and given the current debate over the Russian oil and gas embargo, we would not expect to find this substitution effect for fuel trade.

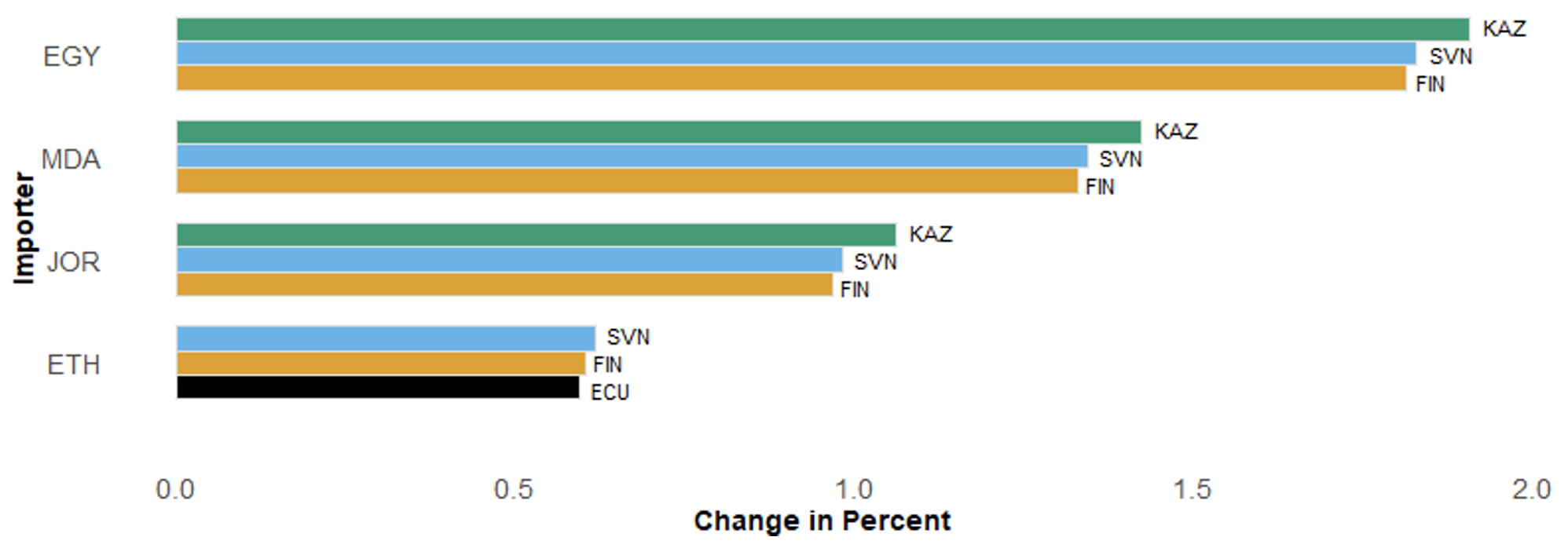

figure 2 Trade diversion after the Ukrainian civil war

notes: This figure reports the change in the value of bilateral trade in 2015, compared to a hypothetical counterfactual world in which the Ukrainian civil war never happened in 2014. On the y-axis, we report the four importing countries (Egypt, Moldova, Jordan, and Ethiopia) with the largest trade diversion impact on the Ukrainian civil war. For each of these importers, we provide three bar graphs representing the relative trade growth of the three main alternative partners (Kazakhstan, Slovenia, Finland, and Ecuador).

What do our findings mean for Ukraine’s global supply chain? Here, we can draw on case study evidence from Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the subsequent civil war in Ukraine’s Donbas region. Apply a general equilibrium estimation technique for structural gravity similar to Kwon et al. (2022), we estimate a decrease in Ukrainian exports following the outbreak of the civil war in 2014. We then use this estimate to calculate hypothetical trade patterns and welfare levels for countries around the world if this conflict never occurs. Comparing actual and hypothetical trade flows and welfare levels, we understand how this conflict affects the global economy. While it is difficult for us to compare the scale of violence during the Civil War to today, qualitative trends are likely to be similar. We found that in response to the civil war, some rival countries increased bilateral shipments. The countries most affected by the import disruption are Egypt, Moldova, Jordan and Ethiopia. For most of them, Kazakhstan, Slovenia and Finland resemble major alternative partners as their imports from these countries have increased by up to 2% in response to civil war. Looking at welfare changes, however, we find that all countries are worse off than the counterfactual in the absence of a civil war. While it’s no surprise that Ukraine itself suffered the most, even those countries that benefited from the trade diversion (such as Kazakhstan and Slovenia) have seen their overall situation worse from the civil war, as increased export demand does not compensate for the Losses related to trade opportunities with Ukraine.

The future of the global economy

We conclude this column with an outlook. How can the economies of Ukraine and Russia recover from the war once the violence ends and sanctions are lifted? As far as international trade is concerned, much depends on how long the war and sanctions will last, and how the rest of the world reacts. In our research, we estimated the performance of trade relations after the Civil War ended. Here, we find that the trade diversion effects we estimated during the civil war remained almost unchanged for the nine years after the end of the civil war. Unfortunately, our 20-year sample does not allow us to look for longer time periods. Especially in the manufacturing industry, the relocation effect remains strong and unchanged after stabilization. That is, while manufacturing supply chains tend to remain intact during shorter periods of violence, they also remain relocated once replacement occurs. As a possible explanation for this persistence, we provide evidence that periods of (persistent) violence and the resulting trade diversion effects have increased alternative importers’ continued reduction of bilateral trade costs through preferential trade agreements with alternative partners possibility. The relocation therefore persisted as the world economy reached a new equilibrium in which the relative trade costs of (former) conflict countries increased compared to pre-war levels.

This will have repercussions if the war in Ukraine continues for so long that the repositioning of supply chains and subsequent new international cooperation agreements underpin the new structure of the world economy. In this context, our analysis shows that it is difficult for both Ukraine and Russia to recover their international economic status from before the conflict (Chepeliev et al. 2022). A recent visit to Qatar by the German economic affairs minister and talks on improving trade relations could be the first steps in this direction. However, the current consideration of boosting economic and political ties with Ukraine, and even initiating Ukraine’s EU membership process, could be an effective measure to offset the loss of trade access to them from Russia’s declaration of war.

Look original post for reference

[ad_2]

Source link