[ad_1]

Union officials and executives said this was supposed to be the year European wages began to catch up with inflation, but the economic fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has left many EU workers actually facing deeper pay cuts.

Consumers in the region have been grappling with Electricity, fuel, food prices soar and other commodities over six months.But strong euro zone job market, unemployment hit February record low of 6.8%and report labor shortage For many EU companies, that prompted economists to forecast strong wage growth at the start of the year.

Now, many companies, including major employers such as automakers, chemical companies, food producers and steelmakers that rely on Russian and Ukrainian imports, could be in crisis mode.growing risk Energy rationing and shutdowns These are undermining the case for big pay raises despite a booming job market and the need to protect workers from higher inflation.

“Against a backdrop of mounting growth headwinds – including fresh supply disruptions and Russia’s war with Ukraine and record commodity prices driven by China’s zero-coronavirus strategy – unions are likely to scale back their wage demands as corporate profit margins It’s bound to go down. It’s been hit significantly,” said Katharina Utermöhl, senior economist at Allianz.

This supply bottleneck is already affecting car and truck makers due to supply shortages Wire harness provided by Ukrainian factory. This week, German truck maker MAN said it had laid off about 11,000 employees, send them home Pay 80% of wages after similar plant closures and shift cancellations at VW and BMW.

The consequences of the conflict in Ukraine are Hit consumer and business sentiment. The European Commission’s index of economic sentiment in the euro zone has fallen to its lowest level in 12 months, “mainly due to a slump in consumer confidence,” a survey by the European Commission showed on Wednesday.

The outlook for the EU labour market also deteriorated, as consumer unemployment expectations rose sharply, while business employment expectations fell in most sectors, with the exception of services. The Ifo Institute said its barometer of hiring expectations at German companies had fallen to the lowest level since May 2021.

“In general, and especially in this case, nominal wages do not grow as much as prices,” said Enzo Weber, head of research at the Nuremberg Institute for Employment Research. “That means we will suffer real wage losses in 2022.”

Earlier this year, unions in Germany’s chemical industry began a round of collective bargaining for wage increases to be at least in line with inflation, which is expected to exceed 6 percent in 2022.

However, since the invasion of Ukraine has raised the prospect of Russian gas imports to Europe. cut offunion officials agreed to delay negotiations until next month and offered to seek an interim solution.

Michael Vassiliadis, president of the union representing Germany’s 580,000 mining, chemical and industrial energy workers, said: “With the full-scale labour impact of the embargo, every round of collective bargaining will destroyed,” said this week.

Henrik Follmann, head of his family’s namesake chemicals group and board member of the industry’s employers’ association in Germany, said: “There is so much uncertainty and everyone understands that. Yes, inflation is high, yes , we have to compensate our workers, but not in this case.”

Consumer price increases in Germany and Spain approach close 40 year high March. Euro zone inflation is expected to hit a new record of 6.6% when data are released on Friday.

“Wage growth will remain subdued this year,” said Carsten Brzeski, head of macro research at ING. “Unions will choose job security over higher wages.”

He said the arrival of 3.8 million Ukrainian refugees in the EU country could reduce labour shortages, although many of them are women and children who may not speak the local language or are looking for work.

Some governments, including those in Germany, France, Spain and Italy, are trying to soften the blow by lowering fuel prices for motorists and reducing energy bills for poor households. Some countries also plan to raise the minimum wage, in Germany for example, by nearly 30% to 12 euros per hour.

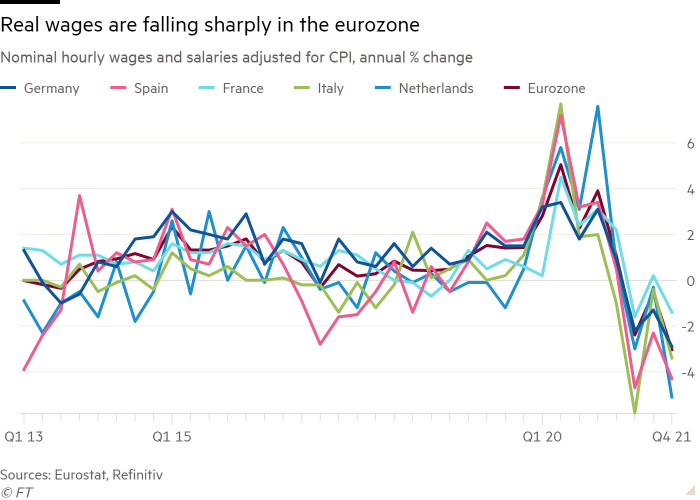

However, in the final three months of last year, nominal hourly wages in the euro zone grew at an annual rate of 1.5%, well below the rate of inflation, which surged 4.6% over the same period, according to Eurostat.

Truckers in Madrid, Spain strike over rising fuel costs © Sergio Perez/EPA/Shutterstock

As a result, real hourly wages fell 3%, the largest drop since comparable data began 14 years ago. This decline can be seen in various indicators of wage pressure. Adjusted for inflation, euro zone negotiated wages per employee (tracked by the European Central Bank) contracted by 1% in the fourth quarter.

The pain is felt across the region. Real wages fell by around 3% in Germany and Italy in the fourth quarter, and more than 4% in Spain and the Netherlands.

Real wages in France contracted by a modest 1.4% as energy price caps capped inflation and a stronger economic rebound, but that remained one of the country’s biggest falls in the past decade.

“The sharp rise in inflation has led to a sharp drop in real wage growth, which is likely to get worse as inflation rises further,” said Anna Titareva, an economist at UBS.

However, Titareva believes that if the Ukraine crisis does not develop into a protracted conflict, wages in Europe will eventually recover.

“In this context, assuming the Russia/Ukraine war will not have a significant impact on the euro area labor market, we expect the upcoming wage round to result in higher settlements,” she added.

[ad_2]

Source link