[ad_1]

Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine will remake our world. How it will do so remains uncertain. Both the war’s outcome and, even more, its wider ramifications, including those for the global economy, are largely unknown. But certain points are already all too evident. Coming just two years after the start of the pandemic, this is yet another economic shock, catastrophic for Ukraine, bad for Russia and significant for the rest of Europe and much of the wider world.

As usual, the impact of refugees is mostly local. Poland already houses the second-largest refugee population in the world, after Turkey. Refugees are also pouring into other eastern European countries. More will come. Many will also wish to stay near their homeland , hoping for an early return. They need to be fed and housed.

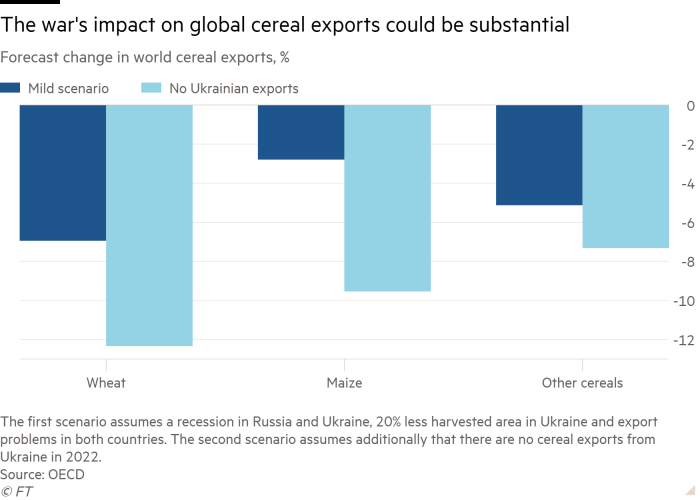

Yet the ramifications go far beyond eastern Europe or even Europe as a whole, as an excellent interim economic outlook from the OECD shows. Russia and Ukraine account for only 2 per cent of global output and a similar proportion of world trade. Stocks of foreign direct investment in Russia and by Russia elsewhere are also only 1-1.5 per cent of the global total. These countries’ wider role in global finance is also trivial. Yet they matter to the world economy, all the same, mainly because they are important suppliers of essential commodities, notably cereals, fertilisers, gas, oil and vital metals, whose prices in world markets have all soared .

The OECD estimates this shock will lower world output this year by 1.1 percentage points below what it would otherwise have been. The impact on the US will only be 0.9 percentage points, but on the eurozone it will be 1.4 percentage points. The comparable impact on inflation will be plus 2.5 percentage points for the world, plus 2 percentage points for the eurozone and plus 1.4 percentage points for the US. Increased prices of energy and food will reduce the real incomes of consumers by far more than these gross domestic product losses alone . The real incomes of net energy and food importing countries will also be worse affected than their GDP alone. It is also likely that the OECD’s estimates will be too optimistic. That will depend, among other things, on the duration of this evil war and on the possible spread to China of sanctions or to Europe of embargoes on energy imports.

These expected direct impacts on output are far smaller than those of Covid: in 2020, world output ended up some 6 percentage points below trend. But a full recovery from Covid had not occurred before the arrival of this new shock, which has damaged international relations , enhanced worries over national security, and undermined the legitimacy of globalisation. This tragedy is likely to cast long shadows.

One reason for this is its impact on inflation and inflationary expectations. The US Federal Reserve has become more hawkish. But it still believes in “immaculate disinflation” — the ability to curb inflation without much, if any, rise in unemployment. The European Central Bank also confronts a jump in inflation, to which it will be forced to respond. In practice, the tightening is likely to damage activity and jobs more than now hoped, partly because of financial fragility.

More fundamentally, the emergence of geopolitical divisions between the west, on the one hand, and Russia and China, on the other, will put globalisation at risk. The autocracies will try to reduce their dependence on western currencies and financial markets. Both they and the west will try to reduce their reliance on trade with adversaries. Supply chains will shorten and regionalise. Yet note that Europe’s reliance on parts from Ukraine was already regional.

Economic policy has only limited relevance in time of war. It cannot save those under assault, though it can seek to punish or deter those responsible. But it can and must respond to the consequences. Monetary policy must continue to be targeted at controlling inflation and inflationary expectations, however unpleasant that may seem. But it is possible and necessary for countries to apply their fiscal resources to looking after refugees and offsetting the impact of higher energy and food prices on the most vulnerable. The latter include many in developing countries, especially in net importers of energy and food. They will require substantial short-term support. The special drawing rights created last year could now be used for such purposes. High-income countries do not need them and should give or at least lend them to those countries in most need.

The response to this tragedy will need to be far more than short term. Just as Covid forces us to plan how to deal with future pandemics, so this war must force us to think harder about security in a world more hostile than most of us expected or at least hoped. Energy security will be enhanced by an even faster shift towards renewables. This is no longer just about the climate. In the short run, diversification of sources of fossil fuels will also be essential. Again, it is clear that the west and especially Europe will have to make a large and co-ordinated increase in their collective defence capacity. This will cost money. Europeans have the resources to be more strategically independent. They should use them. So long as the isolationist right remains so powerful in the US, that will not only be right, but wise.

Last but not least, Russia must remain a pariah so long as this vile regime survives. But we will also have to devise a new relationship with China. We must still co-operate. Yet we can no longer rely upon this rising giant for essential goods. We are in a new world. Economic decoupling will now surely become deep and irreversible. I see no way of avoiding this.

[ad_2]

Source link