[ad_1]

This is the goal of a paper by Yang et al. (2022) out in Health Economics. They first provide a nice review of the literature and divide the methodologies around risk taking into type types. I briefly summarize that literature below.

Direct methods. These methods may ask individuals about their attitude toward risk or likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors. A paper by Dohmen et al. (2011) showed that this direct question provides estimates of risk preference that are useful for making predictions about individuals’ actual willingness to take risks. This direct approach is fairly easy to implement within a survey.

Indirect methods. These approaches generally take the form of a lottery. Holt and Laury (2002) measured risk preferences this way over financial outcomes; Gneezy and Potters (1998) use lotteries to look at myopic loss aversion, and Eckel and Grossman (1998) look at differences in risk preferences across males and females. However, estimates of financial risk preferences have been shown to be poor predictors of risk preferences over health behaviors (see Anderson and Mellor 2008; Szrek et al. 2012). However a number of studies have implemented approaches to examine risk preferences over health states:

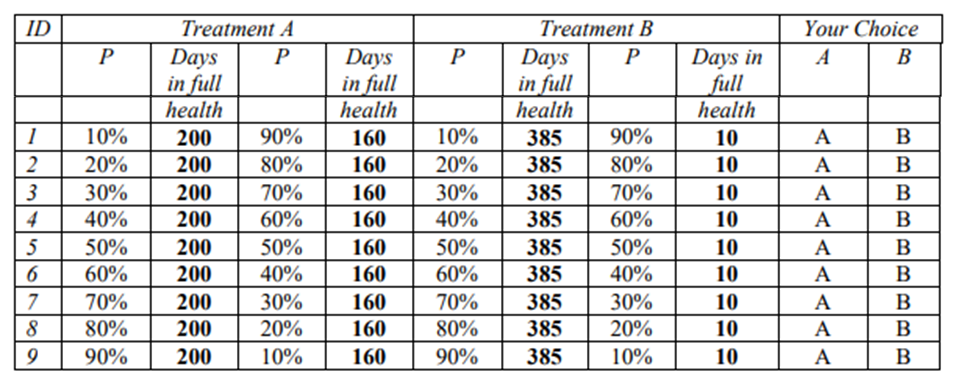

- Arrieta et al. (2017) uses a Holt and Laury style approach but with different distributions over survival duration (see figure below)

- Attema et al. (2013) tests whether survival distributions matter in terms of whether they are framed as absolute levels compared to gains and losses over expected survival (it turns out people are risk averse over survival for both gains and losses).

- Galizzi et al. (2016) examines risk and time preferences between patients and physicians, finding that physicians discount future outcomes less heavily than patients, but physicians and patients have similar risk preferences. The Galizzi use a variant of the Holt and Laury multiple price list approach where the outcomes are days alive and in full health.

- Krieger and Mayrhofer (2012) examine patient preferences over health states (ie, ill vs. not ill) and monetary outcomes incorporating both risk aversion and prudence. They find “risk-averse and prudent behavior in medical decisions, which reduce the (average) treatment threshold by 41% relative to risk neutrality (from 50.0% to 29.3% prevalence rate). Risk aversion accounts for 3/4 of this effect, prudence for 1/4.”

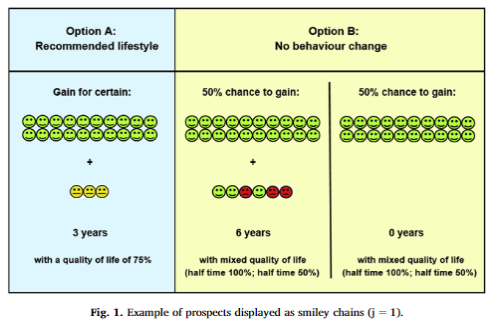

- Rouyard et al. (2018) uses the Attema et al. (2013) semi-parametric utility elicitation using certainty equivalent over binary prospects involving life duration.

- van der Pol and Ruggeri (2008) find that individuals “tended to be risk averse with respect to the gamble involving risk of immediate death and risk seeking with respect to the other health gambles”. A follow-up study Ruggeri and van der Pol (2012) finds similar results.

The Yang et al. paper continues by examining risk preferences over health states and risk preferences over risky behavior using a survey approach. The direct method is, well, direct. It asks:

How would you rate your willingness to take risks with your health? Please write a number

between 0 and 10 in the box below, where 0 means ‘Not at all prepared to take risks’ and 10 means ‘Fully prepared to take risks’.”

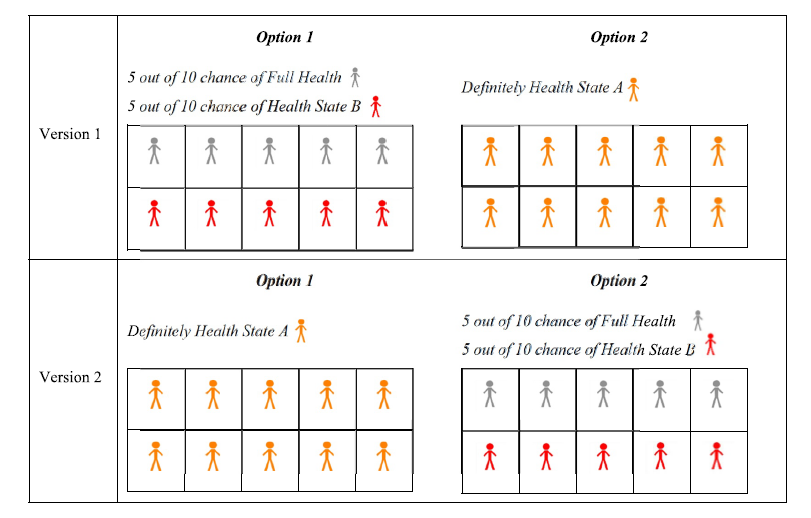

Indirect elicitation of risk preferences is based on a standard gamble approach of one option being risky of being in good vs. bad health and the other giving a certain outcome of mediocre health.

The authors also aim to validate these risk preferences in terms of how well they are correlated with risky behavior. Risky behavior outcomes are defined as smoking status/regular smoker; frequency of drinking five or more alcoholic drinks; and non-adherence taking the full course of a medicine . Using both direct and indirect approaches, they find that:

…risk preferences elicited using the direct approach can better predict health-related risky behavior than those elicited using the indirect approach.

This finding should not be surprising as the topics covered in the direct approach are more closely correlated with the risky behaviors analyzed. Further, while risk preferences do of course play a part in risky behaviors, so does the utility of such behaviors. It is very possible that risk preferences over health states are correlated in some way with utility over risk behaviors. For instance, risk averse individuals may be generally careful people, but may enjoy risky behavior (eg, drinking or smoking) as a stress release. Alternatively, risk averse people could be less likely to take a full course of a medication if they are risk averse over the side effects. Thus, the finding that direct elicitation better predicts risky behavior is not surprising, but it does not provide that the indirect method is not better for measuring risk preferences over health states. More research on this topic is certainly needed.

Arrieta et al. (2017) approach

Galizzi et al. (2016) approach

Rouyard et al. (2018) approach

Yang et al. (2022) Approach

[ad_2]

Source link