[ad_1]

The business world is starting to recognize the economic impact of Long Covid: “Where Are the Workers? Millions Are Sick With Long Covid.”

The message is getting to the mainstream media: “Long Covid is destroying careers, leaving economic distress in its wake,” Consider this Dec. 9 quote from the Washington Post article:

“Patino caught Covid-19 more than a year ago. Instead of getting better, chronic exhaustion and other symptoms persisted, delaying her return to a restaurant job and swamping her goal of financial independence. After reaching what she calls her ‘hell-iversary’ last month, Patino remains unable to rejoin the workforce. With no income of her own, she’s exhausted, racked with pain, short of breath, forgetful, bloated, swollen, depressed.”

Multiply this story several million times and we can quickly see why the American workforce is short millions of people. We want to discuss this in detail. So, this is part 1 of a two-part series about Long Covid. We think it explains the rise in average hourly earnings, the fall in labor force participation, and the transfer of money from labor to capital. Financial-market implications for the rest of this decade are huge, in our opinion.

1. What Does Long Covid Mean for Financial Markets?

What I want to present is a new set of slides that were prepared by an organization that is not in the financial markets. They are devoted to post-viral diseases, and they have developed great data systems on post-viral diseases and now on Long Covid. In our work at Cumberland, we see the evolution of Long Covid as a huge development worldwide and particularly for the United States and for the US economy and the financial markets. At Cumberland Advisors, we have strategies involved in stocks and bonds, which we are implementing for clients, that involve the recognition of Long Covid as a serious issue.

2. If you look at the slide for a minute, this the technical definition of Long Covid. It is a post-viral disease. It has an acronym, as most things do, and it’s PASC, which stands for “post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2.” So, you’ll see the technical term PASC as the description of Long Covid.

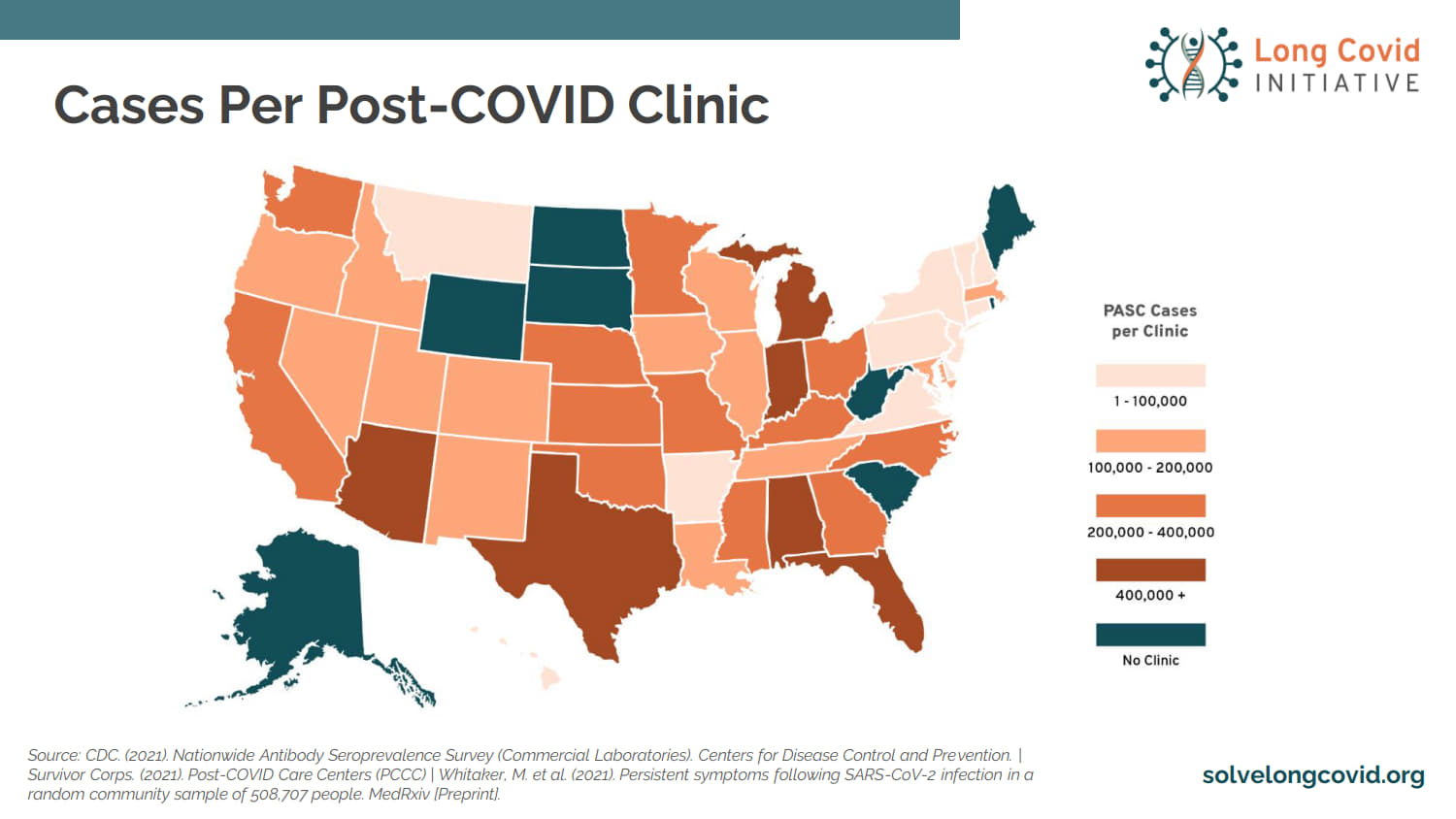

3. Two years ago, there were no Long Covid clinics in the United States. We didn’t have the problem. They are evolving continually as more cases are identified and more people in the healthcare system realize that this is a post-viral disease involving millions of people. This is a chart depicting how many post-Covid clinics are in the United States right now. The number continues to grow.

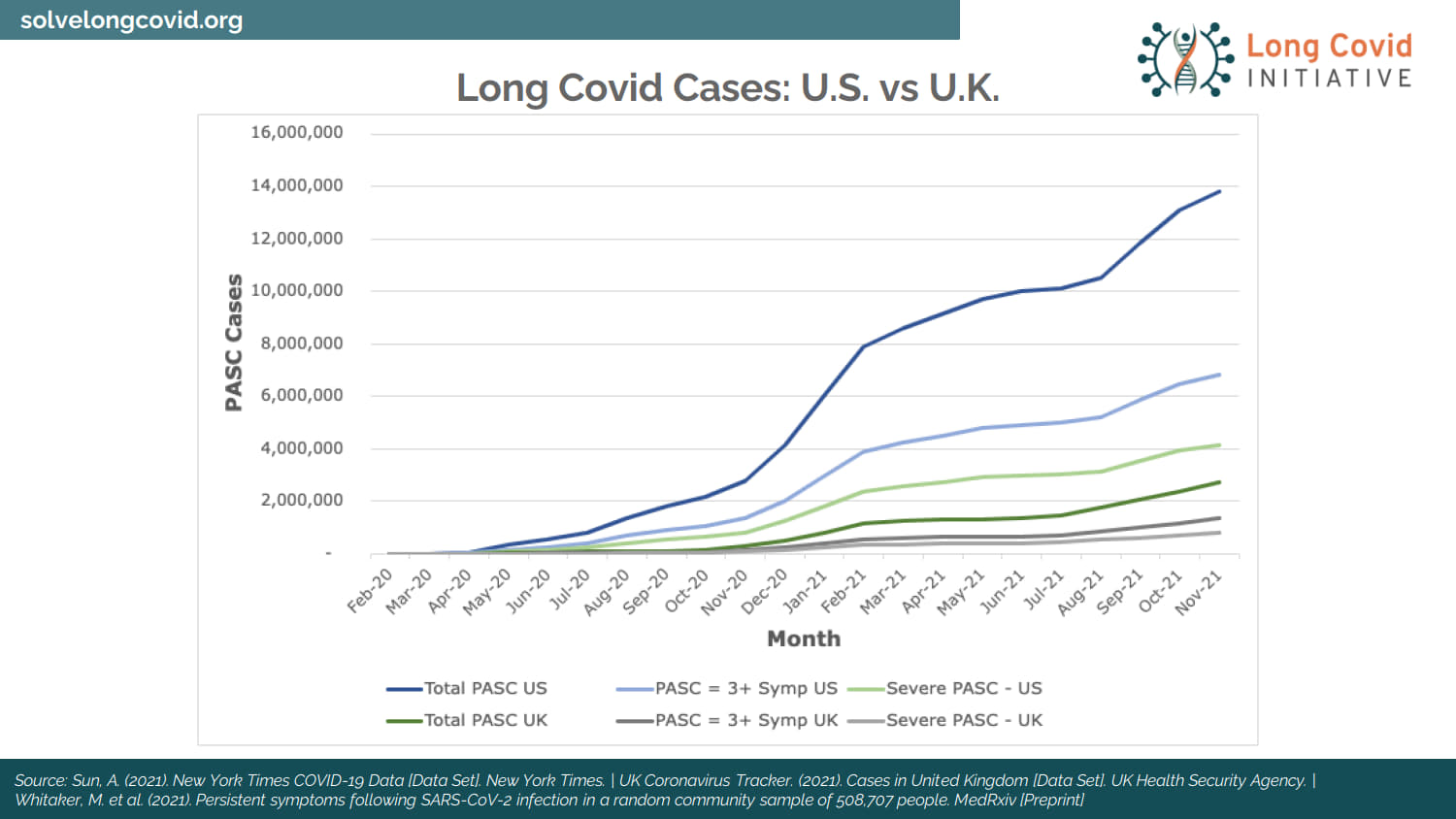

4. This is the distribution of cases of post-Covid around the country. Remember, post-Covid starts with getting the disease. You may have been cured; you may have been treated; you may have had a mild case; and later, you develop symptoms of partial, temporary, or permanent disability of various types. These are the folks who survived Covid, didn’t die, with or without treatments, and then evidenced post-Covid symptoms.

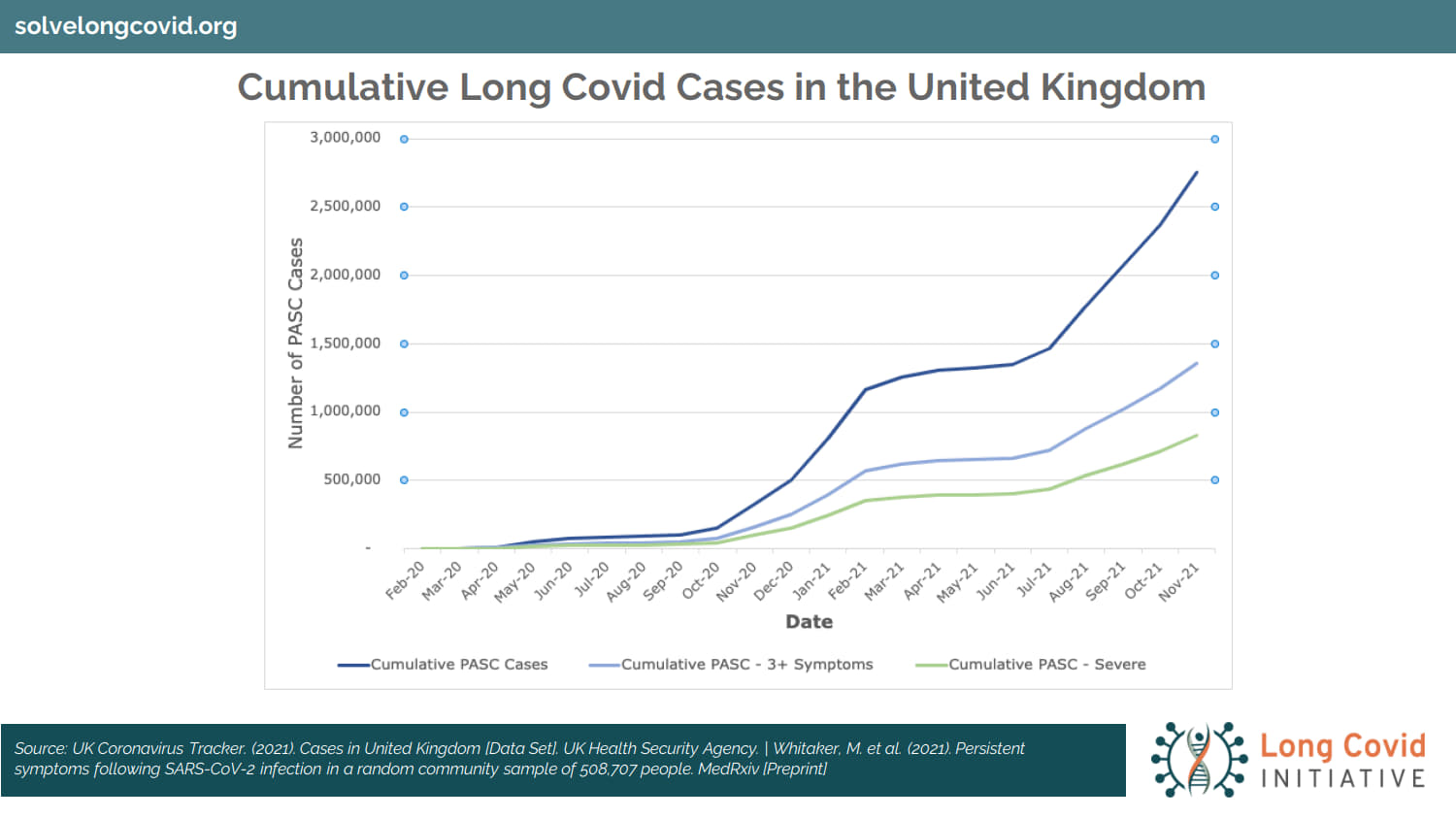

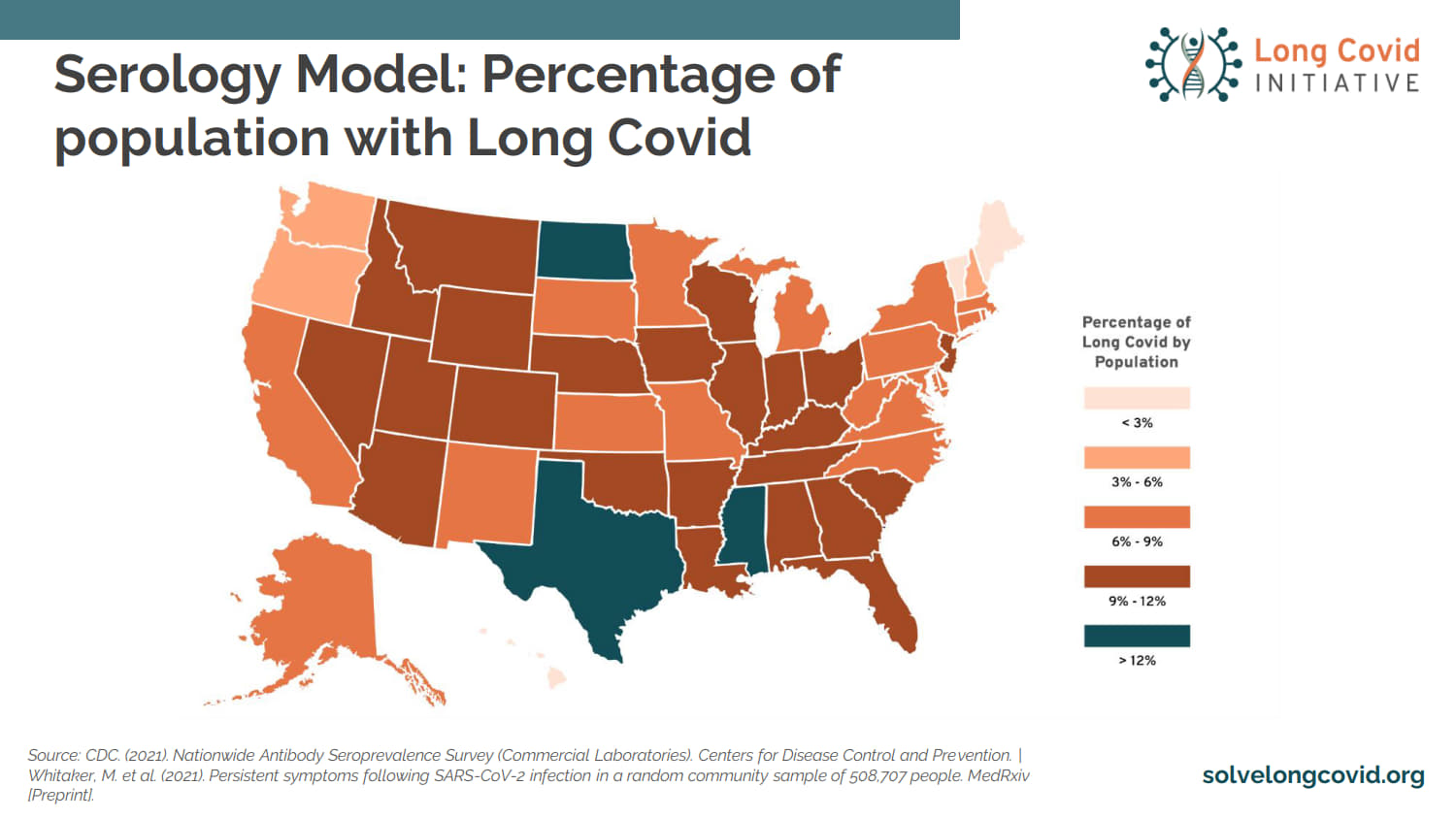

5. Here’s a depiction, a graphical distribution, of moderate, severe, and total cases in the UK. Why do we put up the UK? Because the United Kingdom has 67 million people and a national health system and is able to track these cases, define them, and deal with the treatments. The UK is six to nine months ahead of the United States when it comes to Long Covid data. Why? Because we have 50 different states. We do it differently in the US. In many places we don’t even get a record of Long Covid until somebody’s hospitalized. We have a hodgepodge of data. It’s a weakness of the American system. It’s awful when you compare it to other places in the world. We use the UK as a reference. Remember, in America, we have five times the population of the UK.

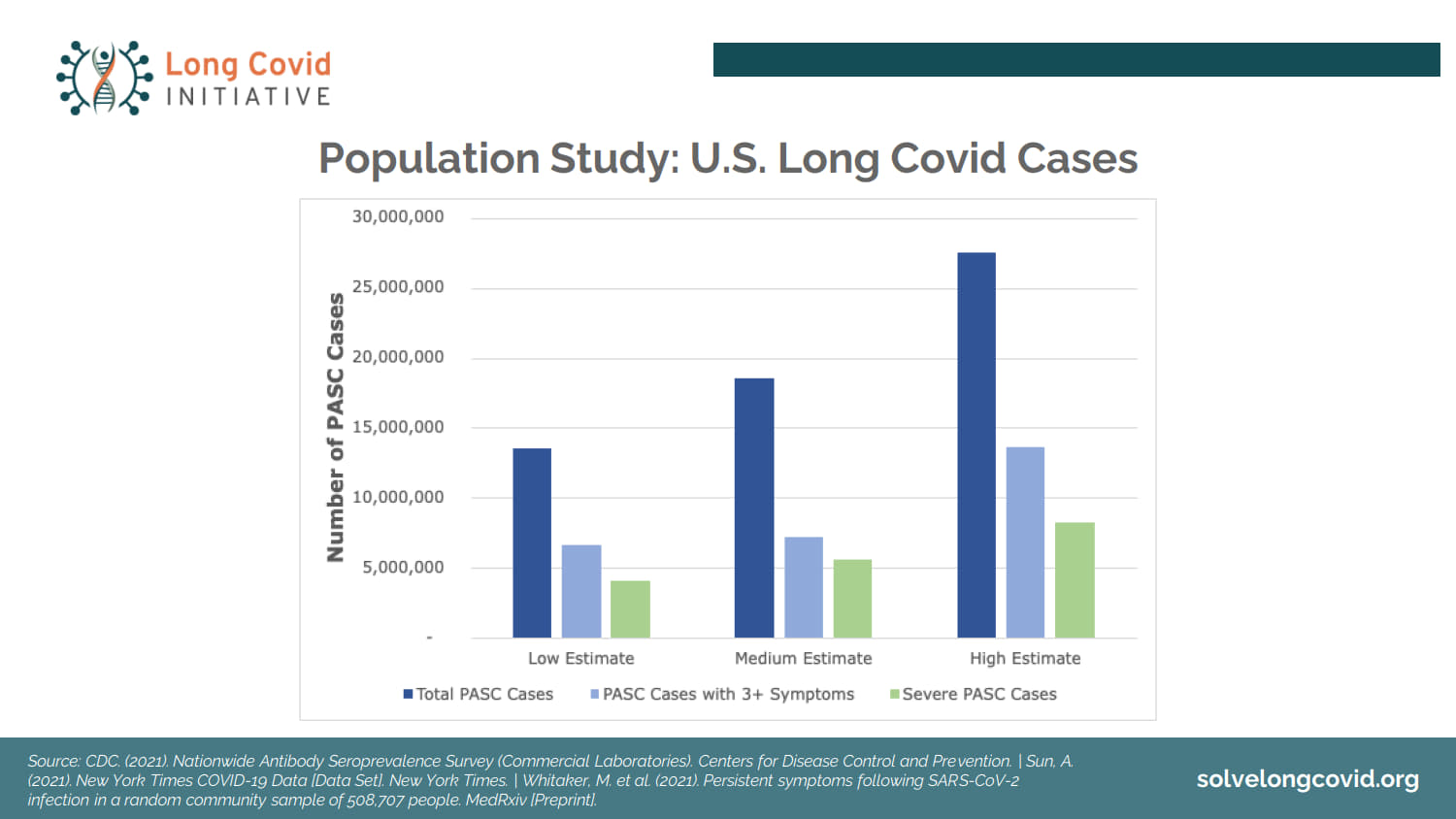

6. Here’s where we are in the US. These are projections; they are developing; this data is changing daily and weekly and monthly.

7. Here’s a population study and estimate on cases. We don’t know today how many cases will be in existence a year or two from now. What we do know is, we’re talking about a disease syndrome — post-viral, post-Covid disease — that will measure in the millions of people. It already is. How many millions is an unknown.

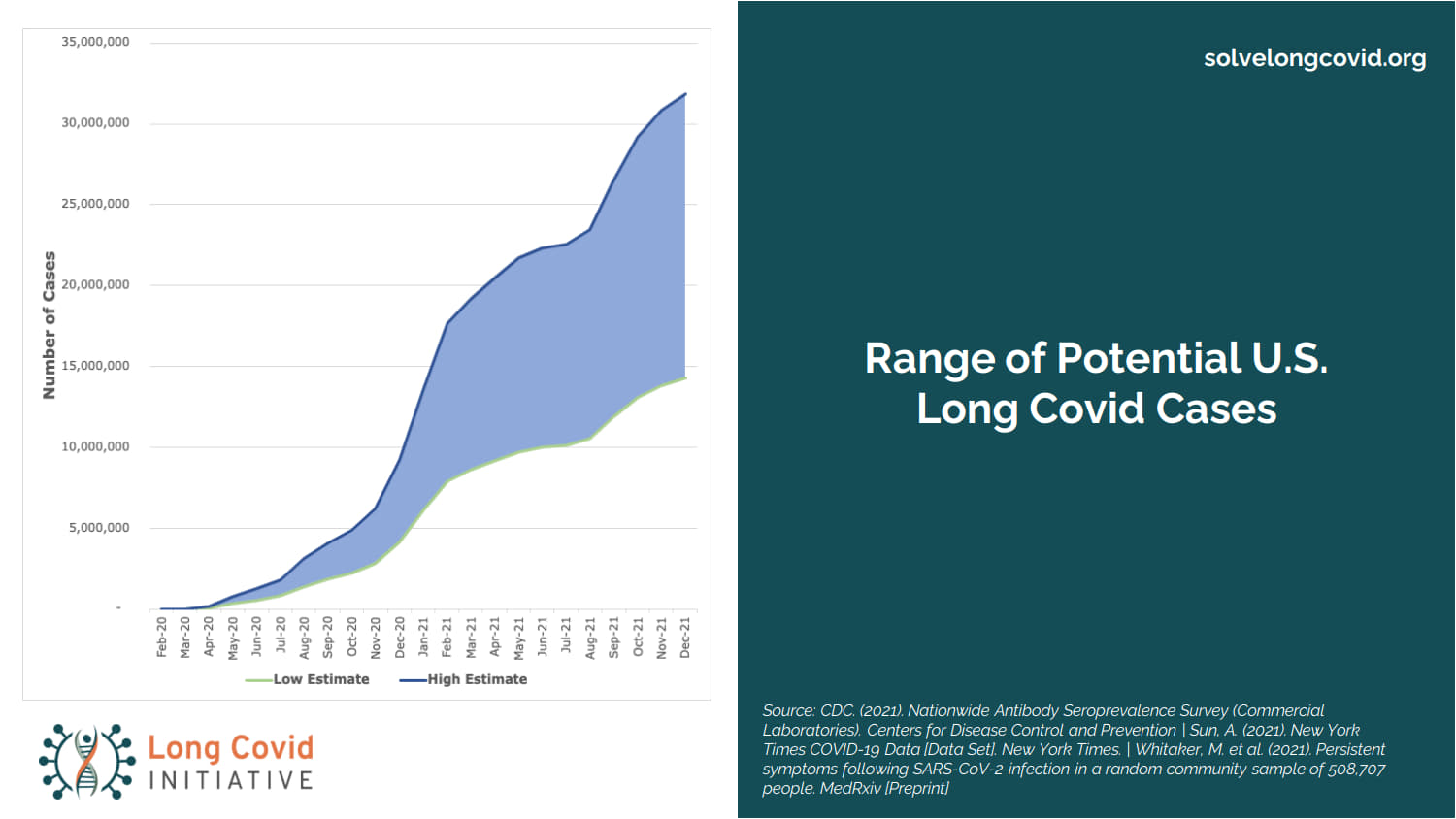

8. There’s a range, an estimate done by the Long Covid Initiative group. These are guesstimates. They are refined guesses, as incoming data is absorbed and analyzed. These are constantly changing numbers. But clearly, when you think about the United States and its population of 335 million people, you can see how large an impact Long Covid may have and already is having.

9. Here’s a comparison between the UK and the US again. This is as of October 2021, but all lines are headed in the direction you see.

10. Here’s a model that uses a different technique to estimate Long Covid; and that’s a good thing, because if we use two different approaches and we get close to the same information, that says we’re close, our estimates are close — they are not exact, and this is a changing environment — but they’re close.

Source: Kotok_12.9.21-LCI-Presentation, Cumberland Advisors, David Kotok

~~~

David Kotok: Let’s talk about what this is. If we have people who have Covid, regardless of age, and then subsequently they develop a condition which disables them, temporarily or permanently — it could be a breathing disability; it could be some other symptom — what medical research is finding about Long Covid is that it may be a blood disease; it can reach into all your organs; it’s not just a respiratory illness, flu, or cold. It’s a substantial long-term, post-viral condition that defines Long Covid. And this mechanism is now creating folks who are disabled in some way. They could be partially disabled, meaning they can work some of the time. They could also be temporarily fully disabled for a period of time, and that’s an unknown quantity.

When you think about this, we have people who are disabled in some ways, and they are diverse ways, and it all originates from the Covid virus — various types of Covid because we have variants.

If you have a cohort of people in the country who have disabilities that weren’t there two years ago, some of them are in the labor force, say, between the ages of 15 or 16, and their late 60s or early 70s. And that cohort is in the millions of people. Some have difficulty going back to work, and others have difficulty when they do go back to work, and they have to take time off because they are ill. They are suffering from a disease, and the disease is post-viral, but it isn’t visible.

Now if we had the same number of people with polio, for example — which I hope we never see — we would see them, and the country would galvanize around treatment and prevention because it would be visible. In the case of Covid and Long Covid, it’s invisible like Lyme or Mono. You can’t see it. And therefore, you have a mass of millions of people in the labor force that are partially or temporarily and, in many cases now, permanently disabled.

When you take a chunk of people, millions of people, out of the labor force, you get a shock. Wages rise, pay levels rise. There are fewer people to do the work, so we see that in the labor force data. It’s not monetary inflation from the Federal Reserve. It’s payment for jobs when there aren’t enough skilled people to fill them. And that only results in one thing: The economy must reprice labor at a higher level to reach some clearing equilibrium.

Generally, you get new productivity gains when you have to substitute the application of technologies for labor. Why? You don’t have the people, and you have to do something, so you substitute capital investment for labor. That has huge investment implications, and stocks in certain industries, groups, and sectors perform positively as a result.

The economy has experienced a massive shock. It originates in a pandemic — they come along every 50 or 100 years, and we are ill-prepared for them, as we have been ill-prepared for this one. The last one was 1957–58 with the Asian flu, and before that it was the Spanish Flu from 1917, ’18, ’19, ’20, and ’21, although everybody thinks of that as 1918 because of John Barry’s book. I might point out that in ’57 and ’58 a President of the United States by the name of Dwight Eisenhower immediately ordered and vaccinated 17% of the population. He vaccinated the entire military establishment, all of the defense contractors, and the government. Why? He was a general, the winner in WWII, and he knew he couldn’t fight wars against enemies with a sick army. There was no anti-vax; there was no discussion akin to this political debate that is ripping apart our country. Eisenhower did it in 1957. There are precedents for such things. Unfortunately, they don’t make the top of the news.

Bottom line on Long Covid is, it’s a developing situation; it’s worsening; it involves millions of people; and it is an economic and therefore financial market shock. There are winners and there are losers that come out of it.

Stephen, I hope I have time for a question or two.

Stephen Polk: Do most disability insurance policies cover PASC?

David Kotok: Ah, man, is this a big one. The defined disabilities in existing contracts do not have the contemplation of Long Covid. That’s evolving now. So, the answer is, maybe yes and maybe no. And I believe the next shock in medical costs and disability costs will come through the insurance payments. Premiums will have to go up through the disability definitions — we now have one from the Department of Health and Human Services, by the way. Our definition in the US is slightly different from the one used in the UK, which is slightly different from other places; but Long Covid is new, so as it’s characterized and defined, we’ll have more disability definition and therefore coverage. And it will have a price attached to it.

Stephen Polk: Do you have any thoughts on the markets heading into the end of the year?

David Kotok: The markets are dealing with two issues: first, Omicron and how it’s unfolding — by the way, it is about 3.5–4 times more transmissible than Delta, on early indications. This is not conclusive, but we have some warning signs. It may not be any more lethal than Delta. That’s another early indication, but of course for unvaccinated people, Omicron is exceptionally dangerous. We are now seeing reports of superspreading events, and I fear we are in for a surge in the United States that will be blisteringly fast and skyrocketing in cases; and therefore some of them will require hospitalizations, and some of them will be dead, and most of the people will be from the unvaccinated population. That’s how it looks to me.

Stephen Polk: What biotech ETFs should we research?

David Kotok: There’s a bunch of them. I would look at the contents of them, the weights of the stocks in them. In our firm, in Cumberland, we own some biotech ETFs, and we select them based on their contents. There are several. You want to look at the companies, the weights, what those companies are doing, exactly how they are applying technology, and then make an informed decision about the basket. I’m a believer in the basket rather than a single bet. It’s a great thing if you can bet on the right stock the day before they announce a discovery; but I don’t know how to do that, so a basket of them says, I’m in the right territory, and all I need is one of them to succeed; and I want them for their investment merit.

Stephen Polk: Do you think we have already reached peak inflation, or do we still have higher to go?

David Kotok: Well, this is the very fascinating debate over the word transitory, which I’m not supposed to use anymore. I never thought transitory would become a four-letter word, but I guess it has. I’m not so sure inflation goes higher for a long period of time. It may be a temporary shock response. We see that in the history of pandemics from the very beginning, when you had the Pharoah and Moses, to the Peloponnesian War when Athens lost to Sparta because of a pandemic, to the seventeenth-century Italian city-states, right up to today. We had wage spikes because post-pandemic we had fewer people; then we saw new capital investment because you have to make up for the loss of the people. That raises productivity, and the inflation spike rolls over and subsides. The 1957 Asian flu pandemic reveals the pattern. In the US inflation rose in 1957 and 1958 and then subsided. By 1959 the inflation rate was flat.

There’s a study out of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco that established that in the 19 recorded pandemics of the last 700 years the real interest rate fell after the shock, and recession or slowdown followed every single shock (“Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics.”) Are we going to have one now? We’ll find out, but history suggests inflation goes back down to a lower single-digit number, although it may take a while to get there. My own view is, 2.5–3.0% inflation probably when things settle down, and that’s a basis on which we are making some market projections. That means interest rates go above zero, but they don’t go back to 5 and 6 and 7%. It’s not going to happen so quickly. That’s my opinion. That and 50 cents gets you lousy used coffee at a Starbucks.

[ad_2]

Source link