[ad_1]

Bumper US growth and pandemic stimulus helped boost remittances to Mexico and northern Central American countries more than 25 per cent last year to record levels, providing much-needed support to those economies as they struggled to rebound from the coronavirus crisis.

Experts say the pandemic economic recovery created strong US demand for essential and migrant labour. The relative weakness of economies south of the border also meant migrants tried to send more, they added.

“It was a very, very unusual year,” said Dilip Ratha, head of the World Bank’s global knowledge partnership on migration and development. “Resilience and recovery [in remittances] is a global story, in that picture . . . Central America in particular and Mexico, they stand out.”

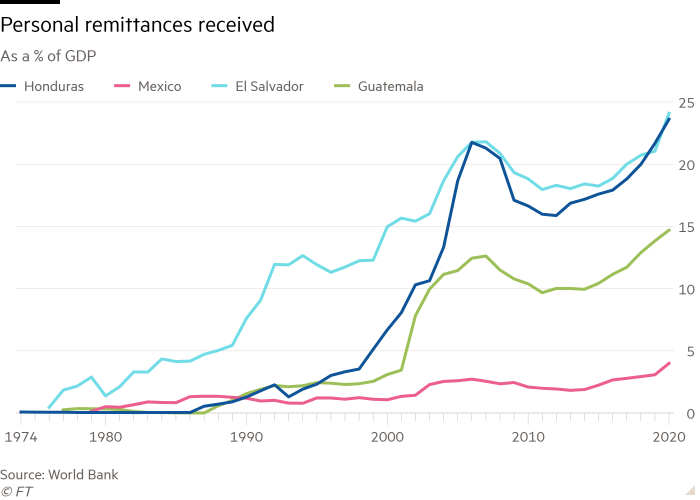

Remittances to Mexico grew 27 per cent to more than $51bn, according to data from the World Bank. Guatemalan migrants sent 35 per cent more, while payments grew 26 per cent in Honduras and El Salvador.

The strength of the US economy — which grew 5.7 per cent in 2021 as it bounced back from the worst of the pandemic — was crucial, as it is by far the main source for money sent to the region. Mexican migrants working in the US recovered their jobs faster than average workers across the American economy, according to Jesús Cervantes González, head of economic statistics at the Center for Latin American Monetary Studies.

Stimulus packages pushed by President Joe Biden also deposited more money in workers’ pockets. Migrants who are legal residents were eligible to receive stimulus cheques and, in a few states, some undocumented migrants also received payments. The money sloshing around also helped boost the broader economy and support migrant jobs.

“A percentage of that ended up in Latin America,” Cervantes González said.

Marco Flores, 31, from the Mexican state of Jalisco, works as a waiter in Kentucky and sends about one quarter of his $5,000 monthly income to his parents and wife back home. He said that there were so many jobs in the US right now because of a lack of personnel.

“People don’t want to work, I don’t know why honestly . . . there aren’t enough people,” Flores, a university graduate, said.

He said he may have to send more back this year to compensate for the bad economic situation at home — inflation is running above 7 per cent in Mexico.

“I’m more worried about the insecurity [in Mexico] and the economic situation.”

Economies in the region are coming to rely on remittances more than ever — they are now equivalent to more than one-fifth of gross domestic product in El Salvador and Honduras.

In Mexico, which has almost 20 times the population of El Salvador, the figure is 4 per cent of GDP. Remittances now account for more foreign income than either oil exports or foreign direct investment.

The remittances sent back help prop up economies that are contending with high unemployment and slow growth. Economists at Bank of America estimated in 2014 that every dollar in remittances spurs about $1.70 in expenditure in Mexico, mostly in consumption, with some in investment.

In 2022, remittances would probably grow again but at a slower clip, experts said, with the unique set of pandemic circumstances fading in an environment of slower growth and higher interest rates.

Last month, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s president, described the country’s emigrants as heroes, comparing them to doctors and nurses saving lives. Flores, working in Kentucky, was unimpressed.

“It’s ridiculous and even outrageous that the president of the country boasts about historic records from people who have to flee their home and send money,” he said. “It’s an issue of national shame rather than pride in my opinion.”

Fermín Martínez, 23, worked picking cherries and apples for more than six months in the US in 2021. He sent money to his mother and to pay for the house he is building for himself back home.

“What you made in a day’s work in Mexico you could make there [the US] in an hour,” he said, adding that he hopes to go back this year, conscious that high inflation on both sides of the border meant he needed to earn more.

The World Bank’s Ratha said he does not see reliance on remittances as a bad thing and that money sent home from other countries is a natural part of development driven by unemployment and low wages.

“The dependence on remittances is, in a good way, very high,” he said. “Remittances are a financial lifeline . . . people truly depend on it, otherwise they would probably fall into poverty.”

[ad_2]

Source link