[ad_1]

Cutting gas flows to Europe is Moscow’s trump economic card if the west imposes tougher sanctions in the event of a Russian invasion of Ukraine. But the EU’s vulnerability to countermeasures by the Kremlin extends well beyond energy.

Policymakers fear the bloc is less prepared than Moscow, where President Vladimir Putin’s “Fortress Russia” strategy is aimed at helping the country weather any deeper sanctions.

From technology suppliers and lenders to goods exporters and manufacturers dependent on raw materials, disrupted trading links would increase inflationary pressures and curb activity for a wide range of European businesses.

“The geopolitical clouds that we have over Europe, if they were to materialise, would certainly have an impact on energy prices . . . but [they] would also impact growth as a result of reduced income and possibly as a result of reduced consumption and deferred investment,” said European Central Bank president Christine Lagarde last week.

Energy dependence

Russia is the EU’s largest energy supplier. About 40 per cent of the bloc’s natural gas imports and nearly one-third of its crude oil imports come from Russia.

The US, a net energy exporter, and EU are discussing the possibility of securing alternative energy supplies.

Gas reserves are below historical levels and prices have soared in recent months, giving Russia increased leverage. “The truth is, Europe has no substitute for Russian gas,” said Ronald Smith, senior oil and gas analyst at BCS Global Markets.

In the event of a conflict, natural gas prices “could easily regain the [December 2021] peak of €180 per MWh”, said Andrew Kenningham, chief Europe economist at Capital Economics. “Electricity rationing could push the economy into a recession,” he added.

The EU would need “difficult and costly decisions” around curbing industrial and consumer demand to survive large-scale disruption to gas supplies until the summer, according to Brussels think-tank Bruegel. Moreover, countries such as Germany have limited scope to switch to other sources of energy in the short term, having moved away from nuclear power and coal.

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia to Germany could also have sanctions imposed on it, while the UK and EU are discussing curtailing new Russian gas projects.

However, as in 2014, when sanctions were imposed on Russia after it annexed Crimea, most economists do not expect gas flows to dry up entirely, as Russia wants to be seen as a reliable energy supplier.

“The ‘Russia gas weapon’ is too powerful to ever be used or, for that matter, to even be mentioned directly in negotiations over this or that disagreement between countries,” said Smith.

Meanwhile, European oil groups such as BP, Total and Shell could see their joint ventures in Russia disrupted if new sanctions were introduced.

Raw material supplies at risk

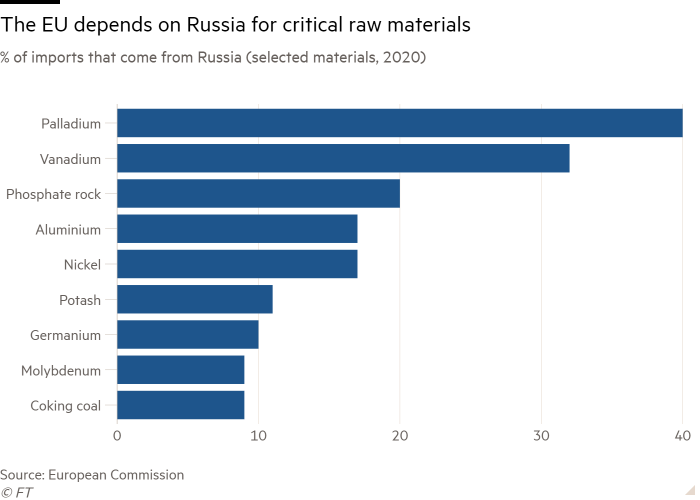

Russia is a leading commodities exporter and features in the European Commission’s list of suppliers of critical raw materials.

Russia supplies about 40 per cent of the world’s palladium, which is needed in the catalytic converters used in vehicles to limit harmful emissions, and about 30 per cent of titanium, which is crucial for the aerospace industry.

Europe’s Airbus, which sources about half of its titanium from Russia, and US rival Boeing both use large amounts of the metal in the manufacture of aircraft. Airbus has said it would “rigorously comply with any sanctions and export control regulations”.

EU officials have also discussed imposing tough export controls on western technology.

Warren Patterson, head of commodities strategy at ING, said sanctions imposed on Russian banks or industries were likely to have “a far-reaching impact on the commodities complex” that could spread across markets in which the country is a leading exporter, including aluminium, nickel, copper and platinum.

Anxious lenders, investors and markets

Russia-Ukraine tensions have fuelled volatility in stock markets this year. Companies with interests in the region, such as Finnish tyremaker Nokian Renkaat or Danish beer producer Carlsberg, have seen their share prices dip in recent weeks. Last month, Italian bank UniCredit pulled out of a potential bid for Russian lender Otkritie.

“Investor nervousness can spread quickly into sectors that should be relatively safer,” said Angel Talavera at Oxford Economics.

Lenders are also at risk, as the ECB has warned. About $60bn is owed to EU banks by Russian entities, nearly four times more than the amount they owe to US banks, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Large amounts deposited in EU banks by Russian entities could be frozen.

Ukraine’s government owes about $23bn to holders of its sovereign bonds. Bondholders have grown increasingly nervous about a possible default or restructuring. The cost of insuring against default has doubled since September.

Investors have said a full-blown invasion of Ukraine would trigger a flight to safety in global markets, away from stocks and into government bonds or other traditional havens such as the Swiss franc, yen and gold.

Shutting Russia out of international payment systems or obstructing its access to US dollars would also hit counterparties in Europe.

Trade and investment downturn

From Polish chemicals to Latvian spirits, trade ties between Russia and eastern EU states are particularly strong in some sectors. Russia is the biggest export market for Latvian goods and the second-biggest for Lithuanian products.

Overall, Russia is the bloc’s fifth largest export market, accounting for 4 per cent of its goods exports in 2020.

But trade from large EU economies to Russia has been in decline since its annexation of Crimea. Less than 2 per cent of goods exports from Germany, Italy or France go to Russia.

“Direct trade links between Russia and Europe are limited and have been reduced since the Crimea crisis,” said Nadia Gharbi, senior economist at Pictet Wealth Management.

The EU remains the largest investor in Russia, driven by Germany, but last year its foreign direct investment in the country was less than half the figure of a decade earlier at $6bn, according to fDi Markets.

Though analysts said most businesses with Russian interests were resilient enough to cope with disruption, Lagarde warned that heightened tensions could lead to “increased costs throughout the whole structure of prices” in the eurozone economy.

“Peace is a lot better than any kind of war from an economic point of view,” she added.

Additional reporting by Katie Martin and Jonathan Wheatley

Trade Secrets

The Trade Secrets Newsletter is the FT’s must-read email on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Written by FT trade specialist Alan Beattie, it is delivered to your inbox every Monday. Sign up here

[ad_2]

Source link