[ad_1]

Case preview

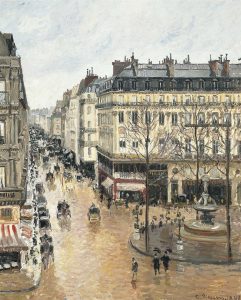

Detail of Camille Pissarro Rue Saint-Honoré, afternoon, rain effect. (Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum)

In the early days of World War II, the heir to a prominent German-Jewish art collector was forced to hand over her family’s Camille Pissarro paintings to the Nazis. Her heirs have sued for more than 15 years over the copyright to the painting, an Impressionist masterpiece that was once considered lost. Whether they will succeed depends on how the Supreme Court decides a very technical question: whether a federal court must hear state law claims under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and apply the state’s choice-of-law rules to determine which substantive laws govern the dispute claims, or do I have to switch to federal common law to choose the source of substantive law?Justices will hear arguments on the issue on Tuesday Cassirer v. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation.

In 1900, Paul Cassirer purchased Pissarro’s 1897 painting Rue Saint-Honoré, afternoon, rain effect. Lilly Cassirer inherited the painting in 1926. In 1939, the painting was confiscated by the Nazis: Lilly was forced to give it up in exchange for permission to flee Germany.

Several members of the Cassirer family, including Lilly and her grandson Claude, ended up in the United States. Other family members, including Lily’s sister Hannah, were murdered in the camp.

In the United States, Lily filed a claim with the United States Court of Restoration, which declared her the rightful owner of the painting in 1954. In 1958, she reached a settlement with the Federal Republic of Germany, demanding compensation. Germany paid her about $13,000; the painting is estimated to be worth about $40 million today. During this time, all parties believed the painting was lost or destroyed, although Claude – who remembers playing in the room where the painting was hung – continued to search for it.

complete painting. (Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum)

Neither the Cassirers nor the German government knew that Pissarro was not lost. In 1951, it was acquired by a California gallery owner who sold it to a collector in Los Angeles. It eventually traveled to New York and then to St. Louis, Missouri, until 1976.

That year, Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza bought the painting and shipped it to his home in Switzerland. In 1992, in cooperation with the Spanish government, he established the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Madrid. He eventually sold the painting to a museum. Neither the Baron nor the museum have adequately investigated the painting’s provenance, although there are red flags that it may have been stolen.

Claude Cassirer never stopped searching for this painting. In 1999, he found it included in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection. He immediately petitioned Spain and the museum to return the painting. He also persuaded Spain to return it through diplomatic channels, but to no avail.

In 2005, after his petition was dismissed, Crowder filed a lawsuit in federal district court in California, where he has lived since 1980. He sued Spain and the museum, alleging California common law claims including conversion and unlawful possession of personal property, and sought restitution of both damage and paintings.

The lawsuit was filed under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. The Acts both give federal district courts original jurisdiction over lawsuits against foreign countries (or their agencies), provided they are not entitled to immunity (28 USC § 1330(a)), and provides that the foreign country or its instrument is no Immunity from litigation where any “property rights in violation of international law are in dispute” and various other requirements are met (28 USC § 1605(a)(3)).

The defendant filed a withdrawal. They raised a number of legal and factual questions, including whether the museum was a Spanish tool, whether it had personal jurisdiction over the defendants, whether the elements of section 1605(a)(3) were met, and whether the proceedings were brought in a timely manner. The district court rejected all of these arguments, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed. The Supreme Court twice rejected the cassation order. Along the way, Cassirer voluntarily named Spain as a defendant, leaving only the museum.

When the district court finally granted both parties’ motions for summary judgment on the merits, only one question remained: Did the museum somehow acquire good ownership of the painting? The question depends on whether California law or Spanish law applies. Under California law, thieves of personal property cannot transfer good title to anyone, not even a bona fide purchaser – so title to the painting was never effectively transferred from the Cassirer family. However, under Spanish law, a bona fide purchaser can acquire effective title to personal property by adverse possession (“Ussukapio”) if they publicly owned it for six years, as the court found the museum did.

But how should courts decide whether to apply California law or Spanish law? While a choice between U.S. law and foreign law is rarely required, a similar situation often arises when federal court jurisdiction is based on diversity of citizenship—that is, when the case raises only state law claims but because the parties are Citizens of different countries (or one is a citizen of one country and the other is a citizen of a foreign country) before the federal court.

under these circumstances, Erie Doctrine, founded in 1938 Erie Railroad Company v. Tompkins, state law applies. The case in 1941 Clarksons Co. v. Stentor Co. Tell the Federal Court to choose which Apply state law by reviewing state choice of law principles. In other words, a federal district court must apply whatever law is applied by a state court in the same state.

what Clarkson In a nutshell, this means that if Cassirer found the painting in his private gallery in Spain and sued the owner in California federal court under plural jurisdiction, the court would ask whether the California state court would apply California. law or Spanish law.

But this is for cases brought under diverse jurisdictions. And what about cases brought under the FSIA?Do Clarkson Apply? Five U.S. appeals courts have resolved the issue. Four of them — second, fifth, sixth and the D.C. Tour — answered yes. Under the laws of these circuit courts, the courts will apply any law applicable in the courts of the state of California. Instead, the 9th Circuit has adopted federal common law principles (which it created in earlier cases) on choice of law. The District Court applied the law of the 9th Circuit, finding that Spanish law was applicable, and the 9th Circuit affirmed.The district court also held that the California choice-of-law doctrine would Also led to the application of Spanish law, but the Ninth Circuit did not resolve the issue.

After 15 years, four trips to the Ninth Circuit, and the death of Claude Cassirer (the case is now being litigated by his heirs), the Supreme Court will finally decide whether to apply California or federal common law Principles of choice of law.

heir to cassirer Three main arguments. First, FSIA regulations (in 28 USC § 1606), if immunity is not available, “In similar circumstances, foreign countries shall be liable in the same manner and to the same extent as private individuals.” Because private galleries would be subject to California’s choice of law doctrine, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection as a So should foreign tools. Second, Congress established the FSIA based on the background principles of federalism that state law, including state choice of law principles, should apply to state causes of action, and nothing in the statute indicates any intent to deviate from that principle. Finally, federal common law on choice of law is very underdeveloped (only 9th Circuit cases and only in this particular case) and completely unrestricted.

The United States has submitted a amicus curiae briefing Two main arguments have been added in support of Cassirer. First, the FSIA is designed to affect only foreign compliance with an action, not the substantive law applicable to that action. Second, the brief draws an analogy to the Federal Tort Claims Act, which exposes the federal government to certain tort claims “in the same manner and to the same degree” as individuals.exist Richards v United States, the Supreme Court interprets the language as mandating the application of state choice-of-law rules — Congress enacted the FSIA in the same language, and later Richards.

museum ambassador Four main arguments. First, jurisdiction granted under the FSIA is more akin to federal issues jurisdiction than diversity jurisdiction, making Erie and its descendants are irrelevant.In support of this argument, the museum points to the text of the statute and the circumstances under which it was enacted: Congress removed foreign states from ordinary pluralism jurisdictions under 28 USC § 1332 instead created 28 USC § 1330. The museum also states Verlinden BV v Central Bank of Nigeria, in which the Supreme Court upheld the FSIA’s challenge to a challenge beyond the scope of Title III, finding that cases under the FSIA arose “under” federal law. Second, the “similar circumstances” requirement of section 1606 is irrelevant here, as this applies only to the sovereign’s commercial conduct, not to its public conduct – which involves the exercise of the sovereign’s peculiar powers – and “expropriation” is essentially is a public act. behavior. Third, the application of federal common law is appropriate here because the lawsuit brought under the FSIA involves foreign policy issues. Finally, one of the primary purposes of the FSIA is to develop uniform standards for litigation against foreign sovereigns, which can only be achieved by applying federal choice-of-law principles.

During oral arguments, the justices may focus on FSIA texts and precedents that show that the topics applicable to federal general legislation are few and far between. There may also be problems with remedies: since the district court, not the Ninth Circuit, held that California’s choice of law principle would also lead to the application of Spanish law, the court may ask for an appellate review of that decision. Finally, there may be some Whether to instruct the 9th Circuit to demonstrate to the California Supreme Court the discussion of the state’s choice of law question, asking the court what law the California courts will apply.

Remember, according to Erie Doctrine always makes strange partners—in a recent major case, Shady Grove Orthopedic Associates v. Allstate Insurance Co. In 2010, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor joined Justice Antonin Scalia’s diverse opinion; Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion Supported by Justices Anthony Kennedy, Stephen Breyer and Samuel Alito.

Whatever the court decides will decide not only the fate of this Pissarro, but all other lawsuits under the FSIA. It may also tell us about the attitude of some justices to federal common law – which was also contested in another case this term, Egbert v. Bull.

[ad_2]

Source link