[ad_1]

The beginning of the year was an eerie echo of 2021. A new variant of the coronavirus has caused a surge in infections around the world, threatening the economic outlook for the year ahead. But unlike the deep recession we’ve seen in 2020, the outlook is for high global inflation and rising interest rates, posing serious risks to the more vulnerable emerging and developing economies.

Last year showed that even without an effective vaccine, advanced economies are more resilient to waves of Covid-19 than expected. Alpha waves have had appalling effects on people’s health, but have done little to dent the global recovery. The result is excess demand and inflation as monetary and fiscal stimulus is stronger than justified.

It should be easier to go through Omicron. Global cases are at record levels, but deaths remain subdued. Vaccines have proven effective in preventing severe disease, and communities are more immune to previous infections, so advanced economies should be better able to adapt.Despite this good news, from International Monetary Fund, OECD and World Bank — suggesting that advanced economies can return to their pre-pandemic projected path of economic output without any long-term damage — may be overly optimistic.

High inflation points to serious bottlenecks in last year’s booming economy, with fewer workers looking for work, and two years of weak investment will hinder the economy’s ability to raise productivity to fuel non-inflationary growth. So the biggest danger in 2022 and 2023 remains inflation as demand exceeds available supply. Headline inflation will fall in the second half of the year as some of last year’s big price hikes outpace annual comparisons, but the main risk to the global economy is that they are too high to be comfortable.

Fed is late response The threat to the United States, which is the biggest threat, is that it may need to raise interest rates from the current zero lower bound “faster or sooner” than officials initially thought. Many well-informed observers now expect rates to rise by four 25 basis points this year as the Fed sells some of its government bond holdings. However, tight monetary policy should not be confused with a highly restrictive monetary policy stance. A nominal 1% rate would still stimulate demand, especially if inflation could well run above the Fed’s 2% target by the end of the year.

The problem for poorer countries is that tightening but still stimulative U.S. policy is likely to spell trouble for them. As the World Bank noted in its Global Economic Outlook this week, tighter U.S. monetary policy could exacerbate an already difficult outlook for emerging and developing economies.

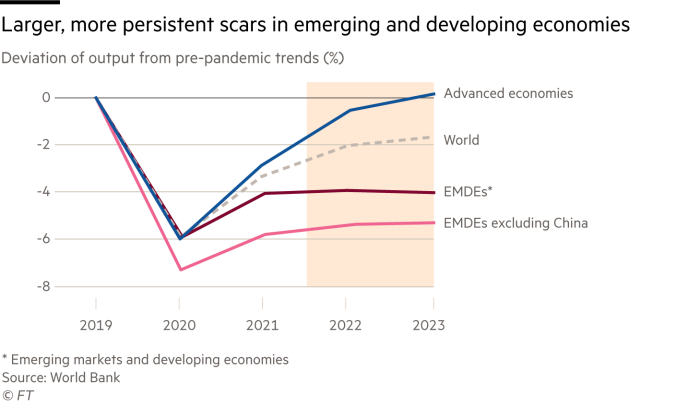

Poorer economies struggled to recover as quickly as advanced economies and lacked the same level of trust and market access to lend freely to protect their people in the early stages of the pandemic. Without financial resilience and generous social safety nets, recessions in emerging economies will be more protracted and recoveries more subdued. The perfect storm was completed by the difficulties these economies faced in obtaining and delivering vaccines to their people.

The two decades in which living standards in emerging economies caught up with their wealthier cousins ??are now over. The World Bank estimates that from 2021 to 2023, real incomes in 70 percent of emerging and developing economies will grow more slowly than advanced economies.

Weakness during a pandemic can also leave larger, more lasting scars. Compared to a scarless (albeit optimistic) assumption in rich countries, the World Bank estimates that the recovery in poorer countries will be nearly 6% lower than pre-pandemic expectations. This further limits their ability to service existing debts, has risen (already increased According to the International Monetary Fund, the share of national income has fallen by 10 percentage points since the start of the pandemic. This could lead to a hard landing, debt distress and social discontent for weaker countries.

None of this will get any easier this year when the Federal Reserve is likely to hit the brakes harder than expected, disrupting markets and tightening global monetary conditions. World Bank President David Malpass said the outlook for 2022 was “unlikely to be favorable for developing countries,” an understatement to some extent.

Emerging and developing economies face different conditions. China has ample fiscal firepower to cushion its economy in the short term, even at the expense of the rebalancing needed in the longer term. Turkey is a prime example of a vulnerable country. High public and private debt and the low creditworthiness of its economic institutions are a toxic mix. Countries in similar situations have already experienced capital flight and are threatened with a vicious cycle of diminished prospects and increased vulnerabilities.

The outlook is tough. The World Bank projects that by 2023, 40 percent of emerging and developing economies will still have national incomes below 2019 levels. Those conditions could prompt a liquidation this year, rather than a rougher ride.

[ad_2]

Source link