[ad_1]

JJ Jelincic achieved an important initial victory in his Public Records Act lawsuit against CalPERS. We have embedded Judge Michael Markman’s order below.1

Jelincic has the upper hand on the issues most likely to embarrass CalPERS, and may also force the giant fund to be less blatant about breaches of confidentiality requirements.

As you will see under “Orders and Writs” on page 2, Markman discovered that the CalPERS Board of Directors held an improper private meeting on August 17, 2020, which was held when Ben Meng suddenly appeared Of a “special” board meeting. After we revealed that his holding of Blackstone’s shares violated the California Conflict of Interest Law, he discovered that the only part of the discussion that was truly a private meeting was the two parts of California Government Code 11126 (g), which allowed performance to be effective for the CEO and CIO. The review, hiring and dismissal of the company will not be conducted publicly. One must assume that these parts of the meeting are related to hiring Meng’s substitutes; Markman more or less said so in his analysis.

We will not analyze this ruling as we usually do because, as we will explain, some things are still in progress and CalPERS can almost guarantee an appeal. Please note that most observers hope that CalPERS will appeal if it loses. Here, CalPERS lost on the most embarrassing issue, that is, the abuse of private meeting privileges, such as improperly categorizing matters that are required by law in public discussions as secret board discussions. Among other things, this discovery amounts to a verdict that Henry Jones, the chairman of the board, has committed a crime. Even though he was only punished for misdemeanorsSince Jones undoubtedly relies on the guidance of employees deemed trustworthy, this ruling should make Jones and other members of the board of directors careful not to trust so.

Keep in mind that CalPERS’s motivation for appealing has little to do with its chances of winning. If appealed, CalPERS can try to insist that the matter is still unresolved and any negative comments on its actions are premature. Since CalPERS mistakenly posted an edited transcript in the public section of the court website (please view our copy here), CalPERS may also be able to suspend the publication of any other sections of the private meeting transcript that has not yet been made public.

Now back to the order. Obviously, Markman has not yet seen the complete minutes of the closed-door meeting. CalPERS detained some parts claiming that they enjoyed attorney-client privileges. Obviously, under California law, even in camera review, well-intentioned and sufficiently high-risk lawyer-client privilege matters may be blocked.

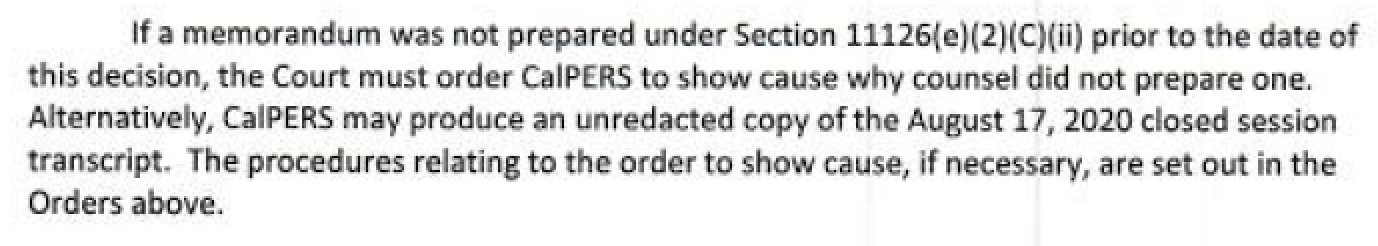

Please note that if there are any actual attorney-client privilege issues, General Counsel Matt Jacobs must submit a memorandum to the board of directors as part of the basis for validating the confidential discussions. Someone told me that during the hearing, CalPERS tried to insist that such a file had been created, but it can’t be found now.

Markman seems to be very submissive again to ask CalPERS to give out his so-called wayward record:

Markman basically said that CalPERS needs to provide the allegedly missing documents so that he can assess its authenticity, or publish the entire transcript, or face sanctions. So this controversy will continue into the new year.

Those who follow CalPERS may have reason to worry that this is an invitation to CalPERS to fabricate the missing memo. This would be risky because the file was never provided to the board of directors, nor does it exist in the board’s record system Diligent.

You will also see Markman ruled that CalPERS does not have to disclose its nearly $600 million in write-downs of real estate assets because they are part of the disclosure exemption provided by the legislature for alternative investments (listed and excluding real estate) and alternative investments. Investment tools. Markman also accepted CalPERS to hide some supporting memos by claiming trade secret status.

Unfortunately, this was because Markman fell, as the judges sadly did, because of the assertion that too much discussion of investment strategies or documents could hurt investors, just like an evil short-headed attack.

Equally disturbing is that Markman described the ruling as the first time any court has considered whether a California public pension fund that invests in real estate through a limited partnership is an “alternative investment” confidentiality shield. In 2010, the California Court of Appeals ruled against CalPERS against CalPERS on this issue, because CalPERS tried to hide documents related to the loss-making real estate investment Page Mill Properties. The judge ruled that real estate is a traditional investment and needs to be disclosed.

The problem is that when these laws protecting private equity and closely related investments were implemented across the United States in the early 2000s (ironically, in response to the settlement of the CalPERS Public Records Act litigation, the litigation required CalPERS to publish information about all of its private equity Fund once a quarter), argue that the company is a fragile thing, too much transparency may give underperforming people (they may go bankrupt because customers and potential employees avoid them) and good people (key employees may be Poached). This does not apply to real estate at all. If its super or management agent withdraws, the valuation of the building will not be affected. And events that do affect value, such as the termination of a lease or the eviction of tenants, become public events because the space is relaunched on the market. Similarly, the sale price is public, so there is no ability for private equity to claim that they (in some way) need to hide their transaction price.

In other words: as early as the Stone Age in the early 2000s, CalPERS and other investors were using limited partnerships and buying shares in REITs. If the legislature wishes to include real estate investment in alternative investments, one would expect it to be specified, as the legislature does with private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, and absolute return funds. The other is “alternative investment vehicles… through which public investment funds invest in portfolio companies.” In the early 2000s and even now, industry professionals would interpret “portfolio companies” as operating businesses. Major brokers like Cushman Wakefield say that the only way a real estate-related business may qualify is whether it is a management company/service provider. But this does not seem to be an argument that Markman relied on. He curiously invoked the view that CalPERS, a real estate fund manager, is closely related to CIM, has established and/or purchased SPACS, and then used them to acquire real estate. How does this make real estate a “portfolio company”? And before that, CalPERS didn’t even seem to claim that any write-down investment was actually or was in SPAC.

Let me briefly remind readers why a trade secret claim should be an impossible start. People want to know if Jelinci’s very competent lawyer, Michael Risher, took so much time to resolve the transcript/closed meeting issue that he didn’t brief the real estate. Things are thorough. Markman doesn’t seem to realize that at the design level of Intel’s proprietary chips, nothing in the private equity or real estate field can reach the level of commercial secrets, which is a very high legal threshold. The only type of investment possible in this area is exotic hedging or derivatives trading strategies that competitors have not yet imitated. These types of strategies, even if they are successful, often have a short shelf life. As we explained in 2014:

For decades, private equity (PE) companies have been claiming that limited partnership agreements (LPA), the contracts between them and investors, should be overall As a trade secret, it is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act laws of any jurisdiction. These private equity general partners argue that the information in their contracts is very sensitive and needs to protect the eyes of competitors, otherwise their unique and vital know-how will be stolen and used against them. In particular, private equity firms frequently and powerfully claim that their limited partnership agreements provide valuable insights into their investment strategies. The industry believes these documents are as valuable to them as the Coca-Cola formula or the schematic diagram of Intel’s next microprocessor chip.

Now we can look at the actual language in the limited partnership agreement. We can see that any skilled legal tool user will guess: the lawyers of the private equity company use the broadest and most general terms to describe the strategy and give private equity funds As much freedom as possible…

When KKR claims that the limited partnership agreement is a trade secret, it is not difficult to speculate that these tax games are an important part of what they are really trying to hide. But now that we can look at a series of limited partnership agreements, it is clear that the taxation strategies of various funds are highly parallel. If there is anything unique, it is a secondary detail related to the implementation of the tax plan, not its goal or design…

We see more of the same situation. In the new round of limited partnership agreements, there are no specific or sensitive details about investment strategies. In fact, just like the “use of proceeds” part of a public securities offering, you may want to describe the investment strategy in the most vague and general terms in order to provide the general partner with the greatest flexibility to enforce his authorization.

Why don’t we throw this back to our seasoned readers. How can anyone have a real estate strategy that rises to the level of “trade secrets”, except that it depends on the rewards of unique illegal activities? There is no super deceptive technical skill to gain an information advantage.

The reason for discussing this issue is that, considering that CalPERS will almost certainly appeal, Jelincic and his lawyers will have to respond. If they defend the discovery of violations in private meetings, they may wish to continue to attack on real estate valuations because the legal interpretation seems to be problematic. Therefore, if we are really lucky, CalPERS will end at the appeal stage.

_____

1 The court issued 12 documents. This is the main ruling. We have not reviewed other materials, which is another reason for insisting on the big problem.

00 2021.12.20 JJJ v. CalPERS Order Partial Grant Writ Application

[ad_2]

Source link