[ad_1]

As political leaders pointed out before the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in November this year, there are key differences in greenhouse gas policies between states: rich and poor countries, fossil fuel exporters and importers, and green countries (for example, Scandinavians) and less green countries, such as Australia.

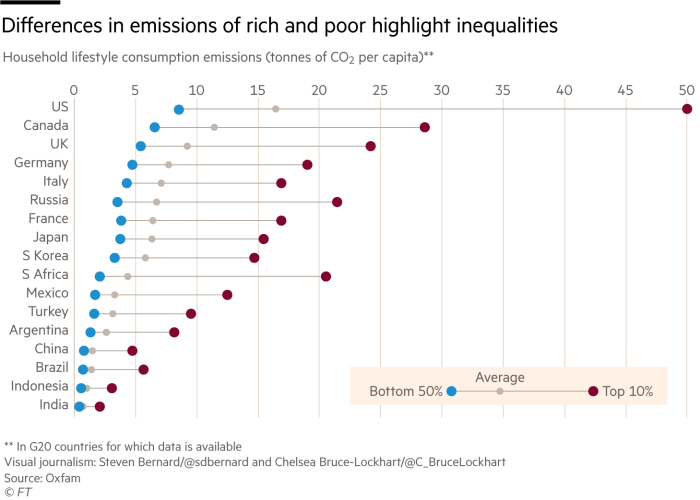

But this may not last long. The struggle to protect the planet is changing in ways that may exacerbate conflicts within countries, especially between social classes. Or, frankly, between the rich and other people. According to United Nations data, the 1% of the world’s highest-income population accounts for about 15% of emissions. This is more than twice the minimum 50% share.

The UN’s 2020 Emission Gap Report stated that limiting the temperature to 1.5°C, as envisaged in the 2015 Paris Agreement, would require the richest 1% to reduce their carbon footprint by “at least 30%” by 2030. Times”. Almost everything the rich do involves higher emissions, from living in large houses to driving larger cars and flying more frequently, especially by private jets. You can eat meat even with a swimming pool. Not to mention holiday houses. Or houses.

Green activists have long opposed environmental inequality, targeting what they call “polluting elites.” But so far, the government has largely avoided a social splitting policy. Instead, they focus on changing the energy structure of all people by reducing the use of fossil fuels and promoting renewable energy. And, selectively, they increase the regulatory burden on the industry.

Consumers bear some expenses, such as green levies on electricity bills, environmental taxes at airports and equipment disposal fees. They are also forced to reduce their carbon footprint by reducing subsidies for electric cars, solar panels and home insulation materials. But these policies are not enough.When they announced a lot Tighter emission targets Before COP26 is held, governments will have to directly curb emissions. Taxes on everything from car fuel to domestic natural gas are the obvious choice. However, they will hit the poor and the rich. Moreover, to make these taxes high enough to change the behavior of the super-rich, it is necessary to impose unbearable costs on the wealthy.

Therefore, a carbon tax for the rich will climb the political agenda. But is tax policy enough? For truly wealthy people, no normal level of carbon-related taxes will act as a deterrent. They can swallow frequent traveller subsidies, taxes on large cars and surcharges on household energy bills. The government may have to go beyond taxation policies and impose restrictions on activities. Maybe use a private jet or a home swimming pool. In most democracies, this is considered extreme. But people can already tolerate regulations such as hose bans.

Climate capital

Where climate change meets business, markets, and politics. Browse the “Financial Times” report here

In addition, if actions are restricted to taxation policies, it is possible to create a world where the advantage of the super-rich (with no repayment) will become greater. In advanced democracies such as the United States, European countries, and Japan, is this politically sustainable? Anyone who believes that it will not change should consider Joe Biden’s commitment to a radical approach to climate policy. The President of the United States is also not afraid of the hope of increasing taxes for rich countries.

What can the rich do to prepare? Well, it makes sense to voluntarily reduce the carbon footprint before mandatory emission reductions. It is not enough to invest more in sustainable development or contribute money to green causes, although such actions do make a difference. What is needed is to reduce consumption, especially luxury consumption that generates large amounts of carbon dioxide and unnecessary headlines.

For those who value a glamorous lifestyle, this will be a price. But we have seen in the pandemic that change is possible. This is not altruism, but enlightened self-interest.

Stefan Wagstyl is the editor of Fortune and the Financial Times. Follow Stefan on Twitter @stefanwagstyl

This article is part of Financial Times Fortune, This section provides an in-depth introduction to philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, and alternative and impact investing.

[ad_2]

Source link