[ad_1]

This is the second part of a series on the weaponisation of finance

Two weeks after Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa held a phone call with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. On the same day, European leaders meeting in Versailles warned democracy itself was at stake. Yet Ramaphosa struck a very different tone.

“Thanking His Excellency President Vladimir Putin for taking my call today, so I could gain an understanding of the situation that was unfolding between Russia and Ukraine,” he wrote on Twitter. Ramaphosa, who has blamed Nato expansion for the war, said Putin “appreciated our balanced approach”.

The South African president is not alone in pursuing a “balanced” position to the war. “We will not take sides. We will continue being neutral and help with whatever is possible,” Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro said after Russia invaded Ukraine. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador also declined to join the sanctions being imposed on Russia. “We are not going to take any sort of economic reprisal because we want to have good relations with all the governments in the world,” he said.

And, then, there is China: an increasingly close ally of Russia. The world’s second-largest economy has scrupulously declined to criticise the invasion of Ukraine.

It might seem that most of the world is united in condemnation of the war in Ukraine, but while there is a western-led coalition against Russia, there is no global coalition. This could have important implications for the future of international finance as countries around the world respond to the dramatic move by the US and its allies to freeze Russia’s foreign currency reserves.

“The sanctions have been earth-shattering,” admits John Smith, who used to be the leading sanctions official at the US Treasury department and now co-heads the national security practice at Morrison & Foerster, a law firm. “They’ve broken the mould.”

The power of the sanctions on Russia is based on the dominance of the US dollar, which is the most widely-used currency in trade, financial transactions and central bank reserves. Yet by explicitly weaponising the dollar in this way, the US and its allies risk provoking a backlash that could undermine the US currency and sunder the global financial system into rival blocks that could leave everyone worse off.

“Wars also upend the dominance of currencies and serve as a doula to the birth of new monetary systems,” says Zoltan Pozsar, an analyst at Credit Suisse.

The weaponisation of finance

The is a two-part FT series on a new era of financial warfare. Part 1 looked at how the decision to sanction Russia’s central bank was taken

China, in particular, has long-term plans for its currency to play a much bigger role in the international financial system. Beijing views the dollar’s dominant position as one of the bulwarks of American power that it wants to chip away at, the flipside of the US Navy’s control of the oceans. The Ukrainian conflict will solidify this view.

Zhang Yanling, former executive vice-president of Bank of China, said in a speech last week the sanctions would “cause the US to lose its credibility and undermine the dollar’s hegemony in the long run”. She suggested China should help the world “get rid of the dollar hegemony sooner rather than later”.

The death of the dollar has been predicted on countless occasions before, only for the US currency to maintain its position. Inertia is a powerful force in cross-border finance: once a currency is widely used, that becomes a self-perpetuating position.

But if there is a steady shift away from the dollar in the coming years, the sanctions on Russia’s central bank might come to be seen not as a bold, new way of exerting pressure on an opponent but the moment when the dollar’s dominance began to decline — a financial Suez Canal.

Analysts point out that previous examples of financial warfare have mostly related to blocking money for terrorism or deployed in specific cases such as Iran’s nuclear programme. Targeting a country of Russia’s size and power is unprecedented, and for better or worse it could become a blueprint for the future, argues Mitu Gulati, a financial law professor at the university of Virginia.

“If you change the rules for Russia, you’re changing the rules for the whole world,” he says. “Once these rules change, they change international finance forever.”

‘It was simply theft’

As Russia accelerated its build up of forces on the border of Ukraine earlier this year and the threat of war hung in the air, the country’s leading financial officials conducted a stress-test of the impact of potential sanctions.

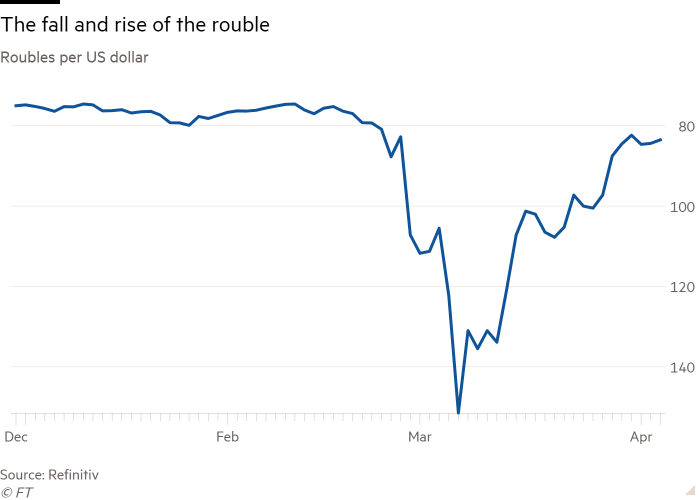

But when one senior Russian banker suggested modelling what would happen if the rouble went over the symbolic mark of 100 to the dollar — a huge jump at the time — the suggestion was dismissed as unrealistic.

By the end of February, Russia had launched an invasion of Ukraine, sanctions had been introduced and a large part of the Russian central bank’s foreign reserves had been frozen. Western governments surprised themselves and Moscow with the strength of their economic response to the war. As a result, the rouble fell to 135 against the dollar, a depreciation of about 50 per cent since the start of the year.

“No one who was forecasting what sanctions the west might impose could have predicted that, when the central bank reserves [were frozen],” Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov said in March. “It was simply theft.”

Five weeks into the war, the situation looks different — at least superficially. The rouble has regained most of the ground it lost in the days after the sanctions were first announced — prompting some Russian officials to claim that the measures had failed.

“This is the beginning of the end of the dollar’s monopoly in the world,” Vyacheslav Volodin, speaker of the Russian Duma lower house of parliament, said on Wednesday. “Anyone who keeps money in dollars today can no longer be sure that the US will not steal their money.”

Volodin added: “The ‘hellish’ sanctions didn’t work. They hoped to collapse the economy and paralyse Russia’s banking system. It didn’t work.”

But analysts say the rebound largely reflects the draconian capital controls and interest rate increases Russia has unveiled in response. They add that the economic impact is undoubtedly going to be severe, regardless of the rouble’s movements.

“It’s very grim,” says Carmen Reinhart, the World Bank’s chief economist. “Modelling at a time like this is an art, so I don’t want to be too precise, but we’re talking about significant, double-digit declines in economic activity and skyrocketing inflation.”

Nonetheless, there are a few tentative signs that Russia could find ways around the sanctions that bypass the dollar-based US financial system. One area is trade. India, a country which is eager to maintain the independence of its foreign policy, has been flirting with the idea of providing a payments backdoor to Russia.

Indian officials say the government and central bank have looked into the viability of a rupee-rouble arrangement — a mechanism the two countries used during the Soviet Union era, which also involved barter trades involving oil and other goods. But officials stress that the issue is not yet settled. Such arrangements are “not easy to undo once the crisis goes,” one official cautions.

Some fear the war is the beginning of a profound shift in the global economy. Larry Fink, the chief executive of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment group with $10tn of assets under management, argued in his annual letter to shareholders that “the Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalisation we have experienced over the last three decades”. One result, he said, could be a greater use of digital currencies — an area where the Chinese authorities have made significant preparations.

Even the IMF believes the dollar’s dominance could be diluted due to the “fragmentation” of the system, although it will likely remain the primary global currency. “We are already seeing that with some countries renegotiating the currency in which they get paid for trade,” says Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s first deputy managing director.

The sanctions could also accelerate changes in the infrastructure of international finance. As part of its push to reduce dependence on US-controlled systems, China has spent years developing its own renminbi-denominated cross-border interbank payments system (Cips), which now has 1,200 member institutions across 100 countries.

Cips is still small compared with Swift, the European-based payments system, which is an important part of the sanctions regime against Russia. But the fact that the biggest Russian banks have been kicked off Swift has given a potential growth opportunity to the Chinese rival.

“Cips has the potential to be a game changer,” says Eswar Prasad, a former senior IMF official now at the Brookings Institution. “China is setting up an infrastructure for payments and payment messaging that could one day provide an alternative to the western-dominated international financial system and in particular Swift.”

Even before the war, there were also tentative signs of a big shift already under way in the composition of central bank reserves — one of the main building blocks of the international financial system.

US government debt has for much of the past century been central banks’ preferred place to stash away rainy-day money, given the size and strength of the US, the safety and tradeability of its debt and the dominant role of the dollar in international trade and finance. In the 1960s, former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing called this America’s “exorbitant privilege”. But that privilege has been eroded in recent decades.

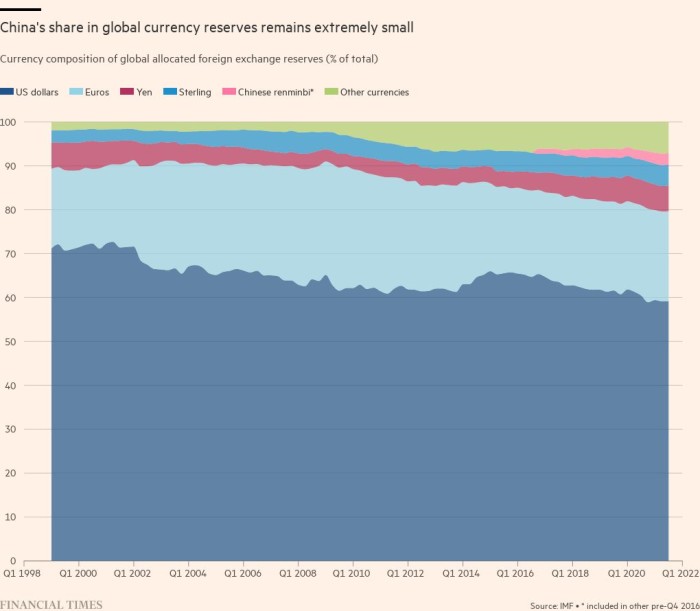

Of the $12tn worth of foreign currency reserves held by central banks around the world at the end of 2021, the dollar accounts for about 59 per cent, according to the latest IMF data. That is down from 71 per cent in 1999, when the euro was launched.

The European common currency is the principal dollar alternative — it accounts for 20 per cent of central bank reserves — but there has also been a marked shift into smaller currencies such as the Australian dollar, the Korean won and above all the Chinese renminbi, according to Barry Eichengreen, Berkeley economics professor who is the dean of studies of the international monetary system.

In a recent report co-authored with the IMF, he called this “the stealth erosion of dollar dominance”, and argued it “hints of how the international system may evolve going forward”. The use of central bank sanctions would probably accelerate the process, he told the Financial Times.

“It’s a huge deal. Freezing the assets of the Russian central bank certainly came as a surprise to me, and it would appear to Putin as well,” he says. “These issues have always come up in the past whenever the words ‘weaponise’ and ‘dollar’ are spoken. The worry is always that this will work to the disfavour of US banks, and you go some way towards eroding the dollar’s exorbitant privilege.”

Yu Yongding, a leading economist at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said in a speech last week that sanctions had “fundamentally undermined national credibility in the international monetary system”. Yu, who used to be an adviser to the Chinese central bank, added: “What contracts and agreements can’t be dishonoured in international financial activities if foreign central banks’ assets can be frozen.”

Is it too early for the death knell of the US dollar?

Yet for all the speculation about the impact of the sanctions, there are also strong reasons to believe they will not promote a shift in the tectonic plates that underpin global finance — at least for the foreseeable future.

Despite the recent rebound in the rouble, there is no easy way for Russia to escape from the impact of the sanctions. Natalya Zubarevich, director of the regional programme of the Independent Institute for Social Policy, says people are expecting results “too quickly” from the sanctions. “Sanctions do not work quickly,” she says. “The other sanctions will have an effect over months, not days.”

Moreover, the threat of US and European sanctions on entities that actively try to help Russia evade the financial blockade will be a major deterrent — even for banks in countries that are amenable to helping Moscow.

Nor is it easy for challengers to displace the dollar. The uncomfortable realisation for countries that might now be nervously eyeing their vulnerability to similar sanctions is that there is simply a lack of viable alternatives. Even Eichengreen says he is nowadays less worried about the dollar’s standing than he used to be, after it survived the “erratic” presidency of Donald Trump.

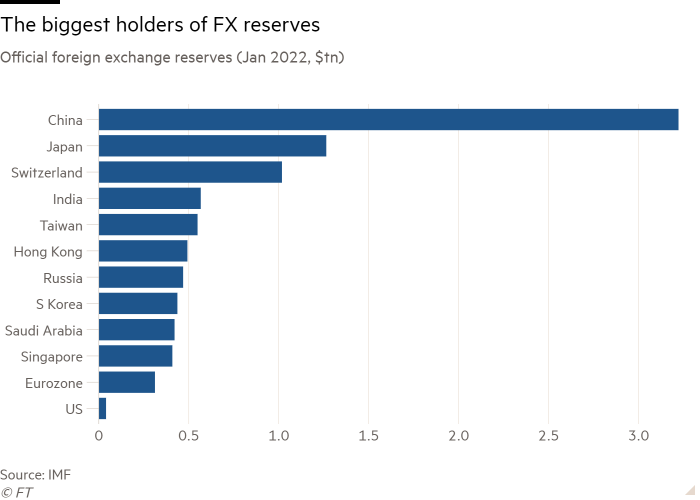

That dilemma is particularly acute for China. With foreign currency reserves of $3.2tn that need to be invested, it has no choice but to have extensive dollar holdings. Outside of Europe and potentially Japan, which have stood shoulder-to-shoulder with America in this case, there simply are not enough liquid financial assets in other currencies to meet that demand.

“We have very accommodative monetary policy, we are very open with our markets, things are easily convertible and we are safe as an economy. Until those things change, the rest of it ain’t changing,” says Brian O’Toole, a sanctions expert at the Atlantic Council and former senior official at the US Treasury. “If we’re acting with all of our partners and allies in this, where else are you going to go? There’s no place else that has anything approaching the level of liquidity and access that the US market has. It doesn’t exist anywhere.”

China also faces an intractable problem if it wants other countries to hold its currency in their reserves. Its capital controls are not as strict as they used to be, but the renminbi is still not a fully convertible currency. In the decade since it first started trying to internationalise the renminbi, the Chinese Communist party has come to realise it can have a global currency that might one day rival the dollar or it can retain tight control over its domestic financial system, but it cannot have both.

Prasad points out that despite the message that countries can no longer rely completely on “their carefully built up war chests at times of war” in light of the “quite dramatic moves by the western economies”, there is simply a paucity of viable alternatives. “The harsh reality though is that the renminbi at this stage is not a big enough player in international finance to be a viable alternative to the dollar,” he says.

Given the profound changes that have taken place in the global economy over the last four decades, it might seem an anachronism that the traditional western allies still dominate the financial world. But for the time being, there is little escape from the hold that their currencies enjoy.

Smith, the former Treasury official, points out that “the death knell of the US dollar in the international economy has been sounded every year” since roughly 2008, when Washington first blocked Iran from using the US dollar for its international energy transactions. But nothing tangible has ever come from it.

“There’s been a lot of hoopla ever since about the US dollar losing its status as the reserve currency and the currency of choice in the energy markets and in the international economy, [but] we have not seen that occur,” he says. “The US dollar has continued to remain strong as a source of stability in international financial transactions, and that is likely to continue even after the dust settles on the Ukraine war that Russia has unleashed.”

Additional reporting by Sun Yu in Beijing and Chloe Cornish in Mumbai

[ad_2]

Source link