[ad_1]

Ive here. We have seen the US and the UK make broadly similar mistakes. Both took ultra-low rates and stuck with them, and before the dot-com bomb era, the Fed’s model was to cut rates by only a quarter and then start raising them. Quantitative easing is, among other things, a tool to extend central bank influence over longer maturities, albeit with an oddly quantitative approach. As Marshall Auerback and others have pointed out, you can control price and quantity, but not both. So it’s never clear how much of an impact QE will have on interest rates.

The central bank orthodoxy, centered on monetarism, also fails to recognize the fact that interest rates are a blunt and asymmetric tool. Selling currency does little to stimulate the economy. It pushes up asset prices and favors leveraged speculators such as private equity, property developers and banks. But raising interest rates can and does constrain financial activity, as businesses plan to assume certain financing costs and increasing them may cause them to cut back on spending. Rising interest rates also directly signal a bearish outlook, another reason for business interests to tread cautiously.

Needless to say, central banks cannot deal with the current inflation driven mainly by energy and car prices. But if they suppress demand, they kill inflation…and a whole bunch of bystanders.

By Richard Murphy, Chartered Accountant and Political Economist.he has been The Guardian reports As “anti-poverty activist and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy and Director of the UK Taxation Research Centre at City University London.he is a non-executive director Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the organization Progressive Economic Forum. Originally Posted in UK tax research

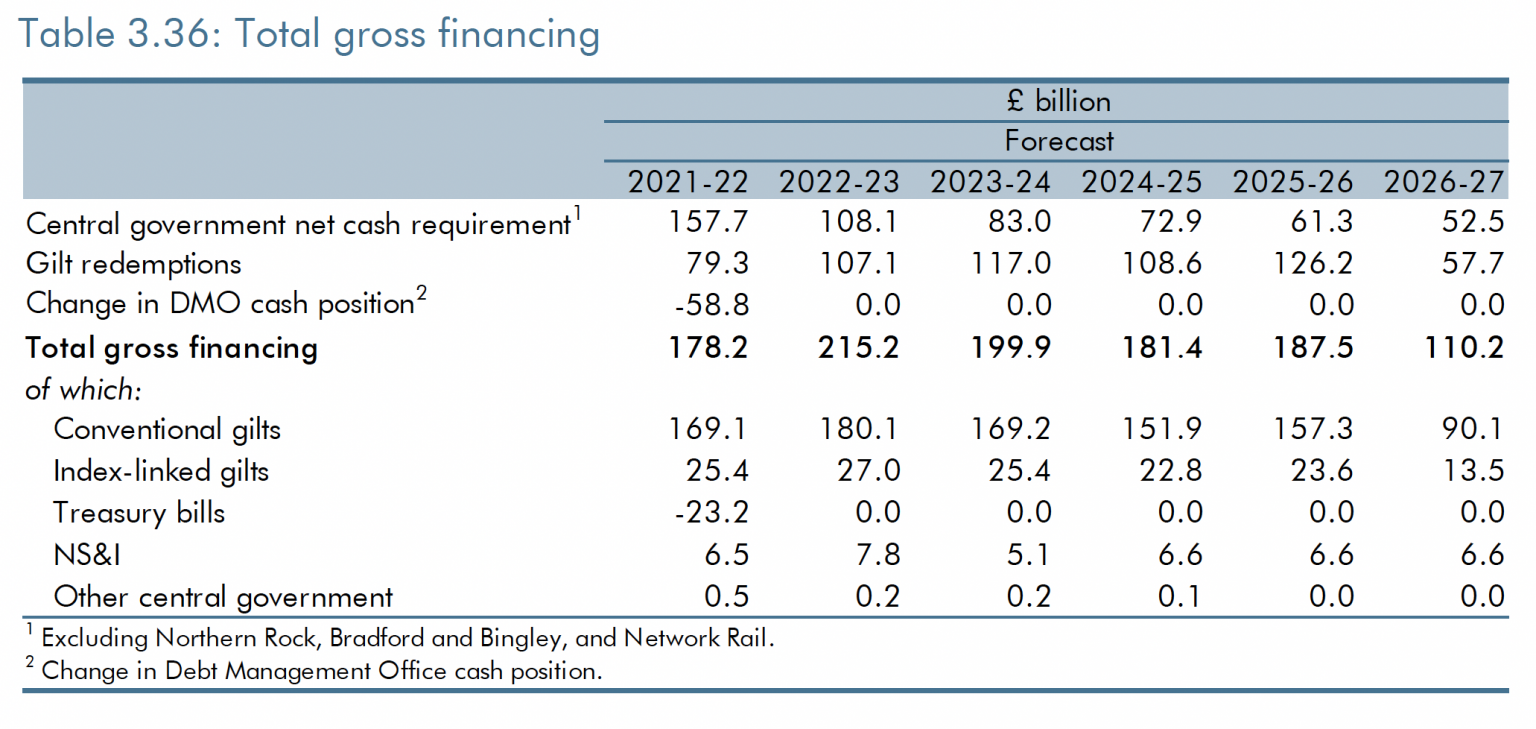

Office of Budget Responsibility posted this comment this week:

This needs to be in its context Borrowing forecast for last October:

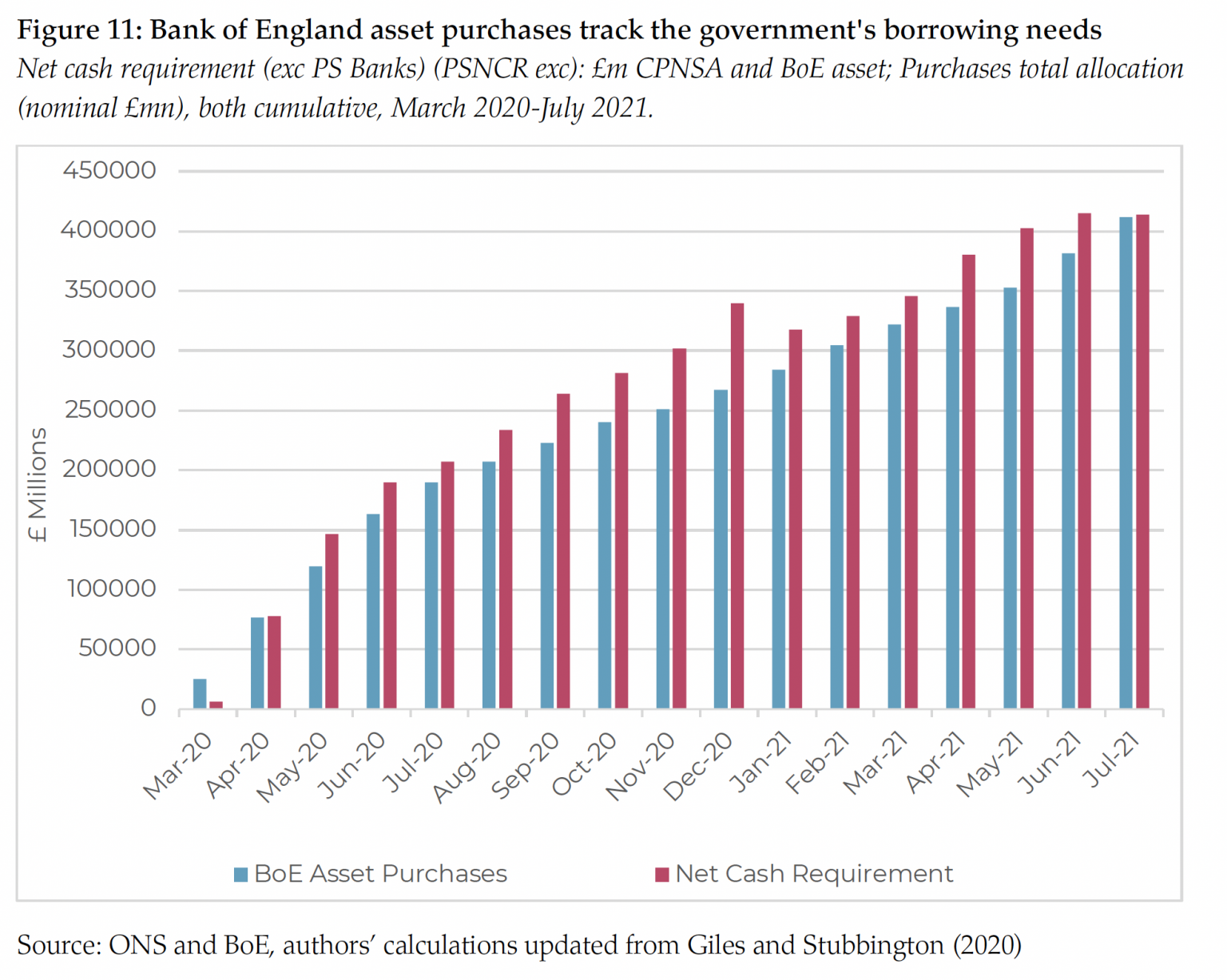

This also needs to be determined in the context of a recent report New Economy Foundation This shows that QE has been funding government deficits, whatever the Bank of England wants to claim:

Now let’s extrapolate a little.

The quantitative easing program is over. The total government cash requirements will be funded by financial markets. Also, QE may start to unwind. This means that the Bank of England will not buy back gilts it owns when it is called. It now owns 33% of all gilts.

This means that, broadly speaking (all figures are estimates, and broadly speaking is good enough), financial markets will have to fund £100bn of Phnom Penh purchases in 2022/23, while the Bank of England will More than £35 million was withdrawn from the market. That means UK financial markets will receive around £140bn in cash calls, compared to virtually none in the past two years.

This is a huge change in terms of funding. The government will require more than 6% of UK GDP to be withdrawn from the effective money supply. What are the consequences?

Frankly, who knows?

We can be sure that this policy is designed to drive down government bond prices by increasing the amount of gilt bonds available in the market. The result will be higher interest rates. So much is to be expected.

It is also foreseeable that without a change in policy, more than £100bn will be withdrawn from financial markets in the coming years.

Other than raising interest rates, no one can be sure what the consequences of doing so will be. However, given that QE has been designed to push investor money into riskier assets, which has apparently happened, we can reasonably expect a reversal of this trend. Riskier assets will be sold. In fact, those sales can be quite substantial. The £140 billion needed for the coming year has to come from somewhere within the financial system, and they won’t be creating money to fund that.

This could mean three things. First, there will be a net selling market in riskier assets.

Second, the net sales market lowers prices marginally.

Third, markets are valued at marginal prices, which means that the overall happiness of those who own the asset decreases.

Which assets are likely to depreciate? Of course the little sow will. But so will stocks. As interest rates rise, corporate bonds will also fall. And with the stimulus also over, house prices are likely to rise as well.

Summing this up, the massive reversal in economic policy represented by the end of QE, rising interest rates and the reversal of QE looks likely to lead to a sharp drop in asset values ??in the UK, and the US could do much the same.

Corporate profits will fall as pension deficits grow. Real investment in the economy will fall.

But what else will happen? In effect, liquidity dries up. Because the market price is expected to fall, no one wants to buy. So the price fell again. Or, the market freezes. Both create chaos. Given the high degree of financialisation of the UK economy, the outcome could be chaotic.

There could be a banking crisis, such as an economic downturn due to falling property prices, a stock exchange crash, or a loss of confidence.

Quantitative easing was carried out in the UK to drive up asset prices. That’s always the wrong thing to do. There are always better options for green or people’s QE. But quantitative easing is done. The intention now is to turn it around quickly. My point is simple. As bad as QE is, it could be even worse to cancel it quickly, something this government and the Bank of England seem to be unaware of, which is indeed worrying.

[ad_2]

Source link