[ad_1]

Germany’s former economy minister Peter Altmaier promised it would act as the “economic locomotive” that pulled the world out of its Covid-19 crisis — but instead the country now looks more like Europe’s laggard.

For a while, Germany was a pillar of relative resilience, its economy shrinking less than most of Europe in 2020. However, for the past year other countries have been rebounding faster and even Italy is expected to regain pre-pandemic levels of gross domestic product before Germany, which is teetering on the brink of a winter recession.

“Germany had a very good first half of the crisis, but in 2021 things reversed,” said Gilles Moec, chief economist at French insurer Axa, adding that weaknesses in the economy were evident “before the pandemic when Germany was already underperforming”.

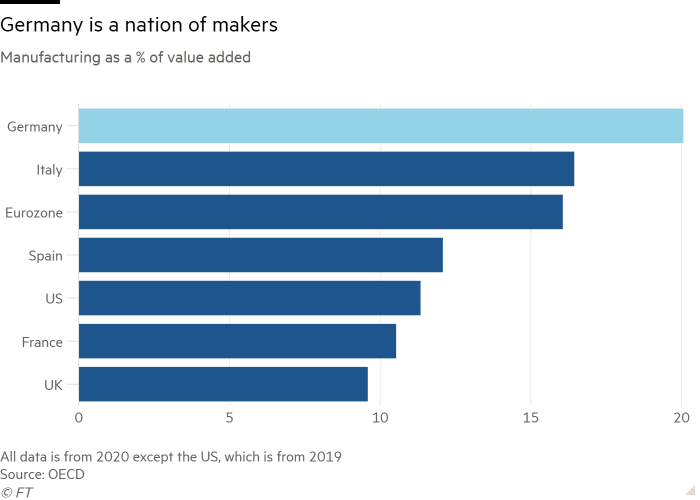

Much of the recent underperformance of Europe’s largest economy stems from its greater exposure to global supply chain bottlenecks that have hit manufacturing, as well as a weaker recovery in household spending, economists said.

The country’s place near the foot of the European growth table was confirmed this month when its Federal Statistical Office estimated that national output grew 2.7 per cent last year — less than half the expected French and Italian rates and well below the 5.1 per cent growth forecast for the eurozone overall.

When quarterly GDP figures are published for Germany and France on Friday, they are set to underscore the diverging performance of the eurozone’s two largest economies. Analysts expect the German economy to even shrink slightly in the final three months of 2021 compared with the previous quarter, while France is expected to grow by 0.5 per cent. This week the IMF blamed “supply disruptions” for downgrading its 2022 German growth forecast from 4.6 per cent to 3.8 per cent.

The stiffening headwinds underline the challenges confronting Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition government, especially as it plans to squeeze public spending next year when Germany’s constitutional debt brake comes back into force.

Robert Habeck, economy minister, said on Wednesday that “the consequences of the corona pandemic are still being felt and a number of companies are struggling with them”. But despite these “major challenges” he expected the economy to rebound with growth of 3.6 per cent this year.

While most economists agree on the sources of Germany’s recent weakness, there is less consensus on whether the country is likely to catch up quickly or remain in the doldrums for a prolonged period.

The answer is likely to hinge on how long supply snarl-ups continue to leave manufacturers short of many materials from semiconductors to lithium — preventing them from fulfilling record order books.

“Germany is an open and trade-integrated economy so it is more affected by the supply problems that have been created by the pandemic,” said Salomon Fiedler, an economist at investment bank Berenberg.

One of the hardest hit areas has been Germany’s carmaking industryin which domestic production slumped 12 per cent last year to 3.1m vehicles — down more than 50 per cent from pre-pandemic levels in 2019.

Overall industrial production in Germany was still 7 per cent below pre-crisis levels in November, while in France it was down 5 per cent and in Italy, the eurozone’s third-biggest economy, it was even up slightly.

Marco Valli, chief European economist at UniCredit in Milan, said Germany was held back by its greater reliance on making vehicles, machinery and equipment. “The pandemic has provided a boost for consumer goods and this is much higher for both France and Italy,” he said.

Economists said Germany’s underperformance in 2021 was also related to a shortfall in household spending, which was still 2 per cent below pre-pandemic levels in the third quarter of last year, while French household spending was down less than 1 per cent.

“France has had a stronger recovery of private consumption,” said Katharina Utermöhl, senior economist at German insurer Allianz. “While Germany’s fiscal response was larger, the fear factor among people has been greater.”

Germany has struggled to vaccinate people as fast as its neighbours, with 72.7 per cent of its citizens fully vaccinated, compared with more than 75 per cent in France and Italy. Because unvaccinated people face rising Covid-19 restrictionsthis is likely to further restrict Germany’s consumer recovery.

Trade Secrets

The Trade Secrets Newsletter is the FT’s must-read email on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Written by FT trade specialist Alan Beattie, it is delivered to your inbox every Monday. Sign up here

Labour shortages are another constraint. Detlef Scheele, head of the Federal Employment Agency, has estimated the country needs to bring in 400,000 skilled foreign workers a year — far more than it has done recently — to offset the impact of its ageing workforce.

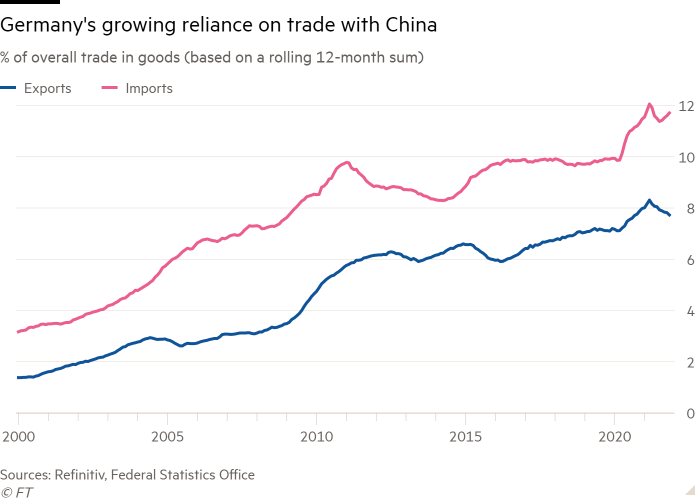

Germany is also likely to be hit by the slowdown in Chinaits second-largest export market after the US. “If the market on which Germany has been betting for many years is disappointing then, as an export machine, you have a problem,” said Axa’s Moec.

Joachim Lang, director-general of Germany’s BDI business lobby group, said the spread of the Omicron coronavirus variant will cause further disruption to factory production in China and other Asian countries that “threatens to affect supply chains again this year”.

Nonetheless, most economists still expect Germany to start regaining lost ground once supply bottlenecks ease and coronavirus restrictions are lifted. With a final fiscal stimulus this year — financed by issuing as much as €100bn of extra debt and €7.4bn from the EU recovery fund — the country “could go from one extreme to the other: from recession to growth champion,” said Carsten Brzeski, an economist at Dutch bank ING.

There were early signs of optimism in IHS Markit’s latest purchasing managers’ index survey of German businesses on Monday, which reported its highest level since September and “tentative signs of easing” in supply chain problems.

UniCredit’s Valli predicted Germany’s economy would lag behind France and Italy again this year — before outstripping them with growth of 3.8 per cent in 2023.

“We expect supply bottlenecks to have faded in 2023 and then we expect the German economy to catch up,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link