[ad_1]

To listen to the audio-voice version of this article, click here.

Every discussion of inflation I hear reminds me of the fable of the six blind men and the elephant.1 Having never encountered such a creature before, the blind can only learn about pachyderms by touch: one touches the torso, the other touches the tail, fangs, ears, legs, and sides. They argue about what the beast is, each person’s description is different, and each person’s understanding is incomplete, limited by his narrow personal experience.

It feels like the inflation debate is a similar experience: one’s analysis and expectations of inflation may be too narrow, highly dependent on which aspects of the CPI data you choose to focus on, your priors on those observations, and (thus) What are you seeing at various prices.2

This is important: there is less inflation than a simple binary problem: Will the CPI rise? Instead, there are a number of factors that drive the components that make up the consumer price index. When we analyze these carefully, we find wide-ranging differences across various consumer goods and services. The nature of these inputs will determine how much inflation there is, how long it is likely to last, and what can be done to combat it.

Consider the four components of the CPI, plus two additional factors that affect consumption, and you get an idea of ??the complexities involved:

car: Restrictions on reopening chip factories to produce semiconductors is a long and slow process – estimated to be as long as 24-36 months. That means we may only have half to one third of the way to supply enough chips for new car production.

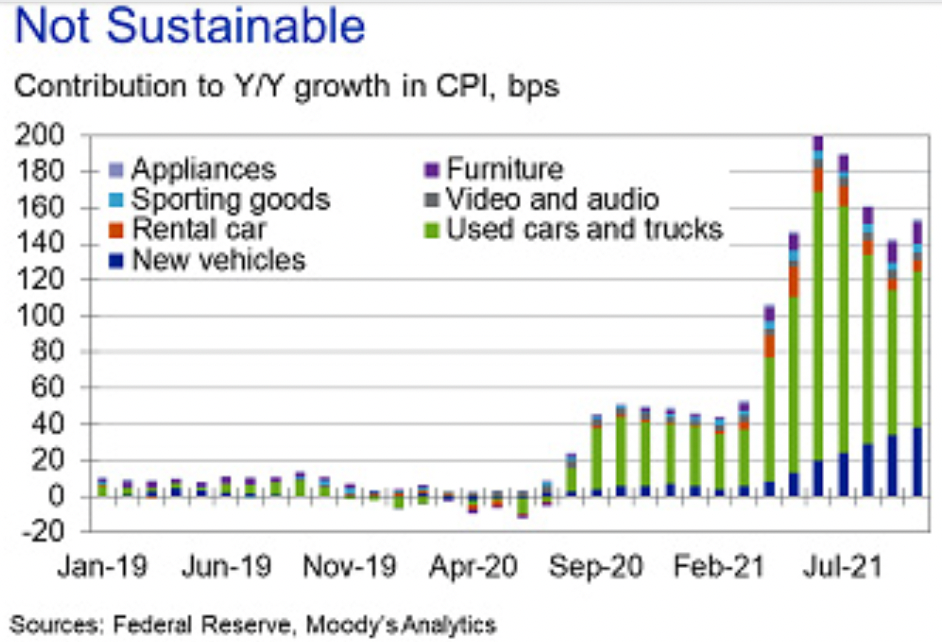

A shortage of new cars has caused used car prices to soar — and there are only a limited number of used cars out there. This had a significant and disproportionate impact on price (see chart).

housing: Insufficient supply of new single-family homes Ten years In production; existing home sales appear to have been impacted by pandemic lockdowns from condos to homes.Housing Specialist Jonathan Miller Miller Samuel Noting that “sales surge as pandemic lockdowns end.” 3 This is especially true in the top half of households where wages are rising and net worth is rising. As more supply comes online and mortgage rates rise, we should see modest price increases.

salary: There are many headwinds in the labor market, but for inflation purposes, I want to draw your attention to three: minimum wage workers, high-skilled workers, and demographics.

minimum wage worker, relative to most other indicators, has been undervalued for decades.The pandemic has given them two things – care about cash in action, which presents an opportunity improve their skills, and negotiating power. It is clear (at least to me) that raising the minimum wage is a belated generational reset.

Demographics Partly due to: Immigration is declining, new business launch, lack of childcare services, coronavirus disease death, early retirement greatly reduces the size of the workforce.

highly skilled worker There has always been high demand, but the pandemic has turned local labor markets in New York, San Francisco, Boston, and others into national labor markets. There has been a lot of confusion as the market adjusts, but valuable employees have found that they can get a big pay raise by switching employers. At least the big resignation of this group is more like a huge work exchange.

vitality: There is a duality between energy sources: On the one hand, oil and gas prices have risen so much that power producers are consuming more coal(!) than they have in years. On the other hand, gasoline prices have been flat for 13 consecutive years, only returning to 2015 levels. Of all the inputs we’ve discussed going up in price,

Energy appears to have the fastest capacity to meet rising demand with more supply. Every commodity trader knows that the solution to high prices is high prices.

Goods and Services: we discussion in november How the pandemic has changed the balance of goods (38.7%) versus services (61.3%). CPI goods rose more than 8%, while CPI services have returned to pre-pandemic levels — prices rose by about 3%. This will eventually return to pre-pandemic levels.move to the goods and away from service It may be temporary, but it’s still inflationary.

logistics: Rebecca Patterson, director of investment research at Bridgewater Associates, observes that the “largest monetary stimulus outside the war” coupled with massive fiscal stimulus has resulted in a “demand shock” driving inflation. Globally, commodity production is now 5% above pre-pandemic levels in 2019, but Patterson noted that demand is up 20%. We have more ships at sea than ever before, but it’s not enough. Added containers and 24/7 ports remain insufficient.

How will these five factors play out over time?

Some may be temporary. Of all these rising prices, energy prices tend to be the most responsive to price increases. On the other hand, it takes 4 to 6 months to build a new home; sufficient semiconductor supply is estimated to take at least 6 months, or a maximum of 24 months; wages have been re-raised – $15 is the new unofficial minimum wage – but By the end of 2022, growth is likely to slow.Building a giant container ship is a tall order 3 year process. In the end, the balance between goods and services will depend on how long it takes us to get the outbreak under control.

How well the prices of these goods and services respond to Fed rate hikes is another question entirely. I’m all for the Fed to normalize interest rates, but I’m not too optimistic that raising rates is the cure we described above.

Pricing in the global economy is dynamic and constantly changing, with many cross-flows, each responding to different inputs: supply, demand, interest rates, fiscal stimulus, geopolitics, consumer sentiment, etc. This is the nature of complex systems. Investors should not engage in overly simplistic, univariate analysis, or even treat inflation as a binary outcome. Instead, it is a rational approach to understand the many factors that affect prices and how they work.

Is the worst of US inflation over? Maybe, but since we can’t accurately predict the future, we should at least try our best to understand the present. That means doing more than just focusing on any one part of the elephant. . .

Before:

Generational reset of the minimum wage (November 30, 2021)

Structural or temporary? (November 23, 2021)

How everyone misjudges housing needs (29 July 2021)

Inflation reset (June 1, 2021)

Change the balance of power? (16 April 2021)

Elvis (your waiter) leaves the building (July 9, 2021)

______________

1. It is made by John Godfrey Sachs‘ 19th century poetry. I find it quite illustrative and I come back to it time and time again. See for example, rentier country? (23 February 2018) and Is the market still an indicator of the future? (August 11, 2008)

2. I don’t mean to imply that all economists are blind to the full picture of the data before them, but if the shoes are right. . .

3. Interesting side note: Miller added, “It’s a bit simple, but land appreciates, buildings depreciate, so most of the recent price spike has been borne by land.”

click audio

[ad_2]

Source link