[ad_1]

A health worker is vaccinated against Covid in Zimbabwe. Vaccination rates in developing countries are lower than in Western countries © Getty Images

As the world enters its third year of grudging coexistence with the coronavirus, global health systems are strained by the highly contagious Omicron variant. But even as countries continue to battle the pandemic, their leaders are considering how to shape a society to be better prepared for the next health emergency.

Not only are they thinking about how to respond more nimbly to emerging pathogens in the future, but they are also thinking about how to address the health inequalities so brutally exposed over the past two years—in rich countries as well as in the global South.

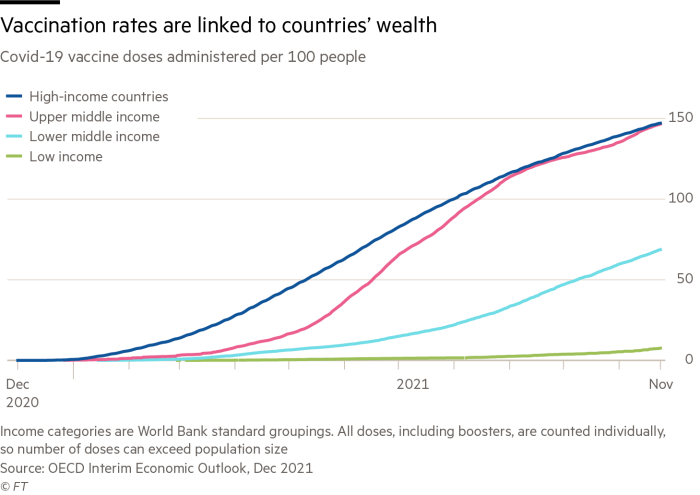

Vaccination remains a huge gulf between the West and developing countries. While nearly 60 percent of the world’s population has received at least one dose of the vaccine, only 9.5 percent in low-income countries, according to research groups Our data world.

The statistics point to both supply issues and the need for better infrastructure to manage a vaccine that has proven to be highly effective in reducing Covid-19 hospitalizations and deaths.

David Heyman, a distinguished fellow at the Chatham House Global Health Program at the London-based think tank, pointed out that many low- and middle-income countries are not used to the large-scale influenza immunization campaigns carried out by Western countries and lack mature systems for large-scale vaccination.

“So it’s not just about the Covax facility [a procurement scheme set up to give people in poor countries equitable access to vaccines] Vaccines will be given to you, it’s a matter of making sure countries are ready for these vaccines and willing to use them,” he said.

For example, African countries may view the urgency of Covid-19 vaccination differently than Western countries because of their different overall disease burdens. Heiman said that at a recent meeting in Ghana, he was told by some African public health leaders that “a vaccine for Covid-19 is not our priority — we need a vaccine for malaria, we need to target a disease that is causing high mortality in our country. vaccine.”

This concern is underscored by data showing the collateral damage of the pandemic to broader public health goals — especially in poorer countries. The World Health Organization said last month that in 11 countries, The highest burden of malaria, only India made progress in fighting the disease in 2020 as the coronavirus crisis hampered the distribution of tests and treatments. Ten other countries, all in Africa, have reported increases in malaria cases and deaths, the WHO said.

Experts fear the advent of other potentially life-saving Covid treatments, such as antiviral drugs, could exacerbate inequality. In the global health community, the overriding concern is not to miss a moment in history that could prompt countries to take joint action to prevent future public health emergencies.

One Report Last year, the agency’s Global Preparedness Monitoring Committee, co-convened by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, blamed “geopolitical divisions” and a tendency for power brokers to negotiate behind closed doors without populations affected by “multiple tragedies.” These range from “vaccine hoarding” to oxygen shortages in poor countries and the “collapse of fragile economies and health systems”.

A Covid vaccination site in South Africa. Scientists in the country provide valuable early data on Omicron variants © AFP via Getty Images

Pandemics magnify inequalities in global health systems, said Ingrid Katz, associate professor at the Harvard Institute for Global Health Research. She worries that as concerns about Covid start to wane for many over the next two years, “the willingness to think about our global neighbours and their importance will diminish.”

As an example of international collaboration that can change the course of disease outbreaks, she cites information released by South African scientists about the sequencing of Omicron, which she says is “critical information to help us at least get a sense of what’s going to happen to us.”

Katz was encouraged by the efforts made in December by the World Health Assembly, the World Health Organization’s policymaking body, to develop an international pandemic agreement. This will “define how we address some of the gaps in global governance and the inequities we’re seeing in this pandemic,” she said.

However, the coronavirus crisis has also exposed flaws in individual countries’ health systems. Around the world, there is a growing realization that if healthcare systems are to prevent, rather than simply cure, disease, they must move beyond the silos that separate hospital care from primary and community care. They must now recognize the role that institutions such as food banks play in sustaining the poorest members of society.

This emphasis on prevention will involve a greater focus on the social determinants of health – factors such as housing, food and the environment. Kieron Boyle, who heads London-based charitable foundation Impact on Urban Health, sees obesity and air pollution as two of the world’s biggest problems, and says there will be increasing pressure on businesses to help address them.

Boyle expects the “social backlog” of the pandemic to be felt strongly in 2022. He noted that people from impoverished backgrounds suffered disproportionately from disease and disrupted employment and education, and they now faced the effects of rising inflation. “This will bring another wave of health crises,” he warned.

[ad_2]

Source link