[ad_1]

For the market, 2022 will be the Year of the Rooster.

Inflation has soared over the past year, far beyond what most central banks can tolerate. So now is the time for policymakers to start pulling back the stimulus that drove asset prices higher after the pandemic first erupted nearly two years ago.

Some central banks have already started withdrawing their support for the financial system.These include the Bank of England, which in December First rate hike in three years.

The most influential of these – the Federal Reserve – has begun to cut back on asset purchases and signaled that it will provide three rate hikes during the year. Investors are increasingly betting that the first could come as soon as March, and that these three may be too conservative. The question is whether the Fed can do this without destabilizing financial markets.

Hence, a high-risk test for nerves. Corporate earnings and economic growth are of course important to fund managers, but the direction of interest rates is a major concern for all asset classes.

For nearly a year, policymakers have shrugged off soaring inflation. If markets are spooked, it is far from clear whether they will now get tough and stick to the expected rate hikes. Many investors doubt that policymakers will be brave enough to raise borrowing costs amid skyrocketing asset prices.

“Central banks cannot be aggressive inflation fighters,” said Salman Ahmed, global head of macro at Fidelity. “It’s not consistent with economic stability because of the debt burden.”

Given that the ECB’s monetary support for bond markets is crucial to maintaining the unity of the euro area, the ECB has some particularly tight restrictions here. The Fed has more leeway because of the dollar’s central role as the world’s reserve currency, but even so, “there is a risk of jeopardizing financial stability,” Ahmed added.

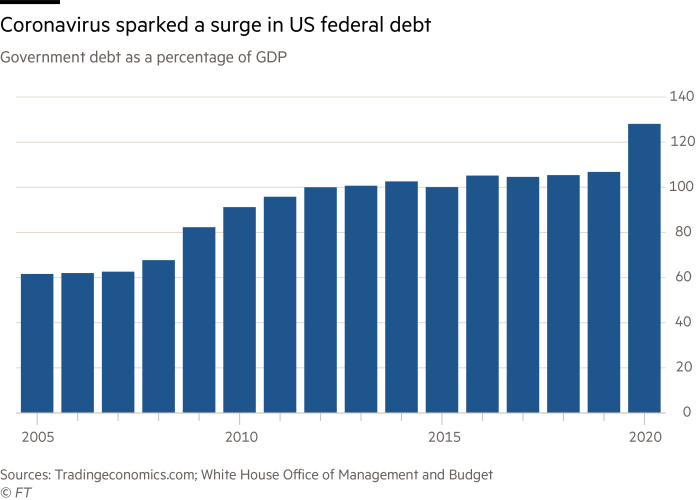

Ahmed pointed out that in 2007 the US public debt was about 60% of the country’s output. Now, thanks in part to the massive fiscal generosity associated with the coronavirus pandemic, it’s well over 100% — which in turn means that higher benchmark rates could offset a significant portion of projected GDP growth, thereby Increase debt service costs.

“This is the elephant in the room,” Ahmed said. “When inflation is below 2%, you can justify dovishness.” In the U.S., it now runs at 7%, cancel this option.

Already, cryptocurrencies and more speculative field stock market stumble As the Fed showed greater urgency in turning to tightening policy, the impact did not spread across the broader market.

Some fund managers remain confident that fiscal and monetary authorities can get out of this predicament without further disrupting economic growth or markets.

Still, the past decade has shown how tricky the process can be. In 2013, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke announced his intention to cut back on the regular asset-purchase program introduced after the 2008 global financial crisis, sparking the so-called “taper scare.” In particular, emerging market currencies and bonds have been hit hard.

On a smaller scale, current Chairman Jay Powell said in late 2018 that the Federal Reserve was “automatically piloting” regular rate hikes, causing turmoil in global stock markets. Within six weeks, he changed his tune, urging people to be more patient. Investors see this, at least in part, as a capitulation to market pressure.

The same tension exists now. Raising rates too late or too timidly could prove to be a self-sabotaging act, making it difficult for future generations to control inflation and accumulating other problems in the long run.

“In order not to let inflation become a problem, we need a steep tightening cycle,” said Luigi Speranza, chief global economist at BNP Paribas. He believes the Fed may have to raise rates faster than investors expect.

But acting too early or too far could stifle a global economic recovery already vulnerable to the vagaries of the pandemic and trigger short-term market shocks.

“The bear’s argument is that if we’re going to [benchmark bond yields], then everything from house prices to growth stocks will fall,” said Andrew Pease, head of global investment strategy at Russell Investments. Some high-growth but thin-profit U.S. tech stocks have fallen by double-digit percentages, underscoring the fact that the impact of these concerns.

Pease said that if policymakers repeatedly tighten liquidity and then pause, it will be a year of “buying the dip” in the market, a pattern already familiar, especially since the onset of the pandemic.

Falling interest rates and resilient demand for government bonds have meant yields have fallen over the past 40 years, raising the appeal of risky assets. These riskier assets could struggle if bond yields don’t keep falling, as many fund managers have become accustomed to throughout their careers.

Pease sees further declines in yields as unimaginable “unless you can see the Fed cutting rates down to ECB levels, a sub-zero world”.

“Look, it’s possible,” he added. “But without that, it’s hard to see what the fundamentals are that are pushing yields down further. I don’t see rates really spiking, but I think we’re at the bottom of that cycle. It seems like it’s over.”

For investors and asset managers, that could make 2022 more difficult to navigate than the previous year and a half.

[ad_2]

Source link