[ad_1]

To listen to the audio-voice version of this article, click here.

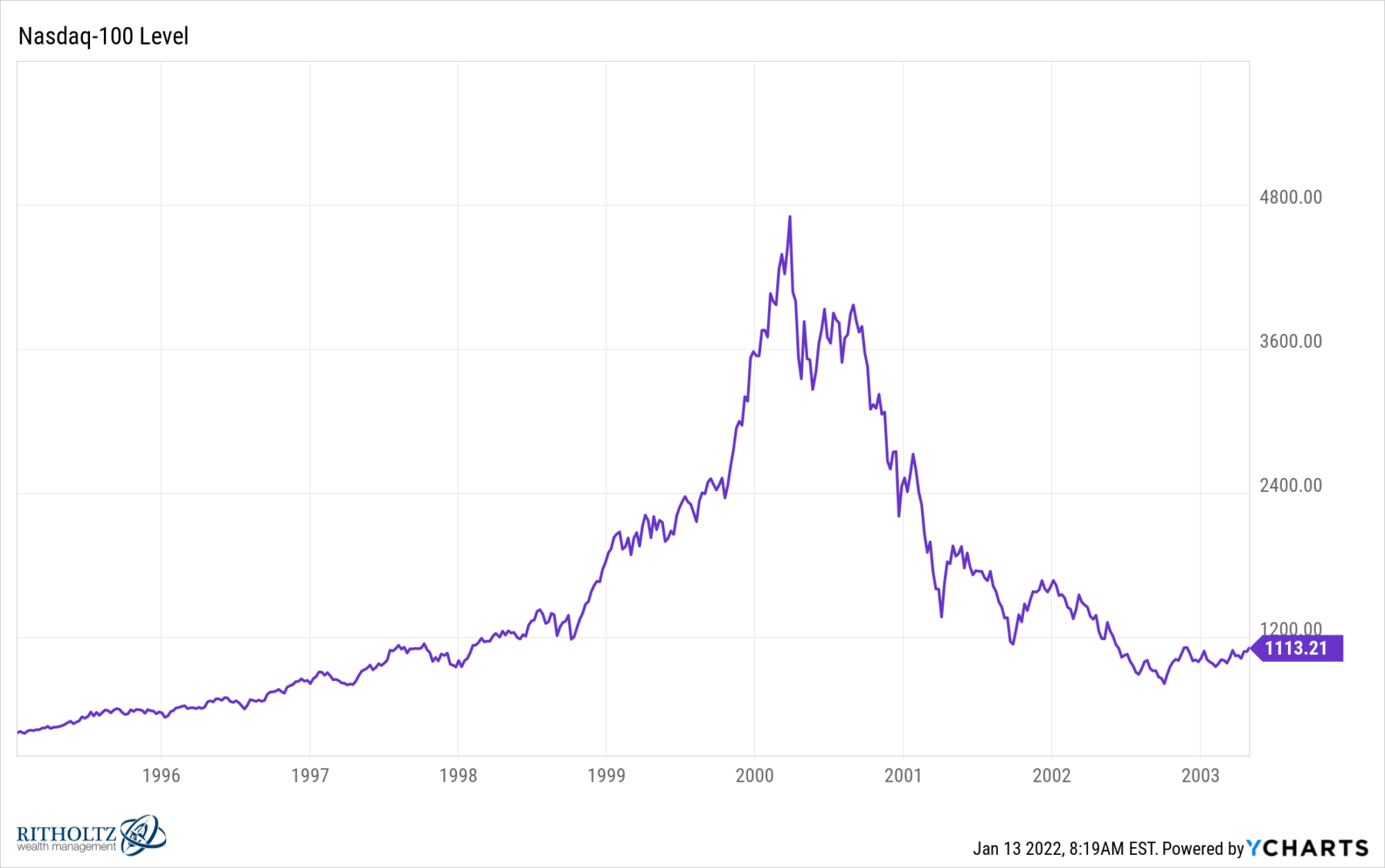

My colleague Michael Butnick wrote a great post How bear markets typically wipe out years of gains was discussed yesterday. (Before anyone draws unfounded conclusions, the title of this article refers to the 2000-02 crash, not the current weakness). Given the rough start to the new year’s trading, for those who haven’t experienced a bubble bursting, it may be worth digging into the various crash scenarios.

It’s easy to understand this intellectually, but it’s not so easy to really understand the forces that affect people’s psyche in a car accident. It’s akin to war: maybe you can imagine what it’s like, but only those who have experienced it can really understand the intensity and scale of the experience.

Due to its long history, Buttnick uses the Dow as his role model. My frame of reference is the Nasdaq 100, traded as QQQ. Nasdaq was where all the activity of the 1990s was. I won’t bore you with the war stories of the trading era; however, being a trader, strategist, or portfolio manager in booms and busts is a once-in-a-lifetime experience; you can’t help but learn about psychology, risk management, human behavior, and more (As long as you’re not hiding under the table).

Since the dot-com bubble burst, we’ve had two other 30%+ crashes: the 2008-09 global financial crisis and the 2020 Covid crash. But none of these examples is a true stock market bubble like the 1990s. Here are the things that really stood out to me in those years:

–Skills and Experience: Good traders use many strategies to their advantage: they can trade pyramids, for example, adding to successful positions when prices are rising. Some average down (not a great strategy), but even that works.Strategies pay off handsomely when used 5X run In the decade that followed, more than four years were less successful.

–capital is critical: Successful, experienced traders get more capital and greater risk tolerance from their firms and clients. They can hold positions for longer periods of time (very favorable in a bull market). In the days before full computerization, they could have exceeded their capital limits intraday. Those who are “proven moneymakers” have more ammo to trade and are on the leash longer.

This worked well in the 1990s, but once it peaked, the results were mixed. Managing these risks is what separates the best deal shops (Citadel, Renaissance, GS) from everyone else who suffers from deal disaster.

–Leverage can be fatal: Some people try to make up for the lack of funds by using leverage or options to amplify their trading results. This just creates an enhanced two-sided bet — more upside, more downside. I suspect Robin Hood and novice traders on Reddit may not fully understand this risk, but will (eventually) figure it out, and it can be painful at times.

–Muscle memory persists: It will take a long time for investors accustomed to buying the dip to forget what worked a decade ago. The Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the LTCM collapse in 1998 both led to a strong recovery and further gains. These experiences make breaking the habit very difficult.

One of the things that made the March 2000-October 2002 period so damaging is that the recovery following each dip subsequently failed. Since December 1999, they have decreased by 15.5%, 10.7%, 31.6%, 21%, 13.9%, 26.8%, 27.1%, 28.2%, 48.9%, 44.8% and 50% respectively. Each of these dips caused buyers to jump in to take advantage of the discount, only to see the subsequent rally fizzle out.new lower lows Happened, with fewer buyers per dip.This is how we ended up working towards what the tech guys said Seller is exhausted.

–Volatility is a 2-Way Street. Risk and reward are two sides of the same coin. Quite often, some of the biggest gainers from recent buyers have seen above-average returns. In the 1990s, the Nasdaq outperformed the S&P 500, which regularly beat the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The crash sent the NDX 100 down 82.9% (see chart above), the S&P nearly halved at 49%, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell “only” 38%.This cycle is the rotation in and out work from home stock.as my friend JC like to say, “The bigger the top, the harder it is to fall. “

–regret minimization: I told this story forward, but when you’re sitting on big gains, especially in your employer’s stock or your own start-up, it might be wise to take something off the table. You still have more stock, so if the market keeps getting you involved, but if not, you have something to show.

–Other asset classes ease the pain: A popular transaction in the mid-to-late 1990s was selling some stock to buy real estate: I distinctly remember clients putting out some stock to buy a vacation property, a bigger home, a better commute, or a better neighborhood. Some rationalized the swaps as stocks continued to rise as a fair trade, but they were happy after the crash. Not everyone is so lucky.

Some final observations: I’m not saying the current weakness is the start of a crash; the economy is too strong, interest rates are still too low, and profits are still strong. My best guess is that this may be the market pricing in 2021 gains and getting used to the idea of ??3 or 4 Fed rate hikes.

Bull markets tend to run much longer than the most optimistic investors expect. I wouldn’t be surprised if we’re still in the 5th or 6th inning of a long, multi-year bull market…

source:

Bear markets suck

Michael Butnick

Unrelated Investors, January 13, 2022

https://bit.ly/3I65YZL

Before:

The end of the secular bull market?not so fast (April 3, 2020)

Correction and rejection (April 17, 2019)

Invisible correction?Bullish, Bartnick says (October 10, 2018)

Redefining bull and bear markets (August 14, 2017)

click audio

[ad_2]

Source link