[ad_1]

U.S. job growth slowed sharply in December, data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics showed on Friday, suggesting the labor market recovery may have lost steam.

But apart from the headline numbers, show With just 199,000 jobs created, a different picture emerges: Economists believe the labor market is much stronger than it first appears, and is actually one of the strongest in history.

“The job market is hot,” said Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of global fixed income at BlackRock. “It’s arguably the hottest ever.”

Here’s the evidence that economists, investors and CEOs see:

plummeting unemployment

While the rate at which employers are adding jobs to the world’s largest economy has slowed, unemployment has fallen sharply in recent months.at 3.9%, currently at its lowest level since last year Pandemic.

To calculate the unemployment rate, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics surveyed the employment activity of about 60,000 households for the month. In December, it showed that 651,000 jobs were created, far exceeding the headline figure of 199,000.

The latter figure comes from a different source, the employer-focused “Corporate Survey,” which surveyed about 144,000 employers and was subject to data distortions related to the pandemic.

A similar situation emerged last month, with household surveys showing Employment 1.1m of revenue. That helped bring the unemployment rate down to 4.2% and presented a more optimistic outlook for the labor market than the 210,000 jobs reported in initial November data.

‘Big resignations’ and record vacancies

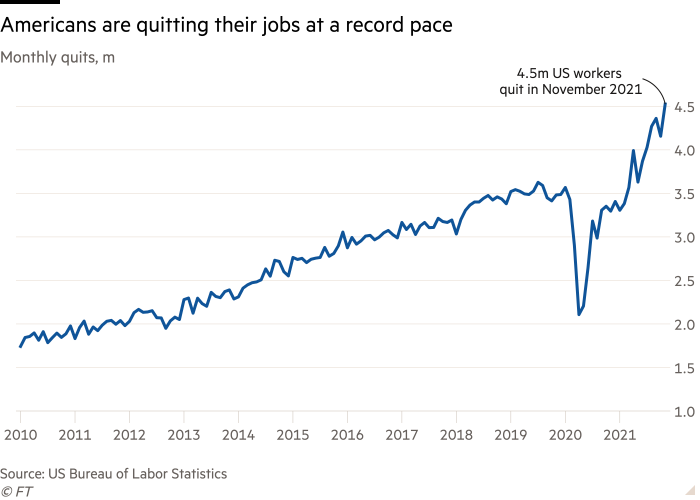

Existing labor shortages have gotten worse in recent months as Americans quit their jobs at a record high.

Data from the BLS this week showed more than 4.5 million workers quit their jobs in November, beating the previous record of 4.4 million set in September and well above the 4.2 million hit in October.

That led to a near-record number of job openings, with 10.6 million vacancies at the end of November, down from the 11.1 million reported a month earlier.

Economists have dubbed the trend “big resignations” as workers aggressively search for new hires, prompting employers to raise wages to stimulate demand.

Tyson Foods warned in its latest earnings announcement that competition for talent is “impacting our operational efficiency,” and FedEx said the labor shortage cost it about $470 million in the most recent quarter.

Meanwhile, Norfolk Southern’s chief financial officer Mark George told analysts in December that a “white-hot” freight market, a strong construction market and Amazon’s warehouses “all over the place” now mean “people have a lot of options”.

Coronavirus-related concerns and childcare issues have also prevented workers from returning to work more quickly, leading to a slower rebound in employment or job-seeking.

The so-called labor force participation rate improved further in December, edging up to 61.9%, but still more than 1 percentage point below its pre-pandemic level.

The participation rate for the 24-54 age group was higher at 81.9%, but also lower than the February 2020 participation rate.

Wages are growing rapidly

To lure workers, employers have raised wages so sharply that economists and Fed officials say they are watching the pickup closely for any sign it will lead to persistently higher inflation.

Fast-food restaurants, retailers and logistics companies are all increasing the launch terms they offer. DIY retailer Lowe’s recently warned that labor shortages could lead to higher wage costs.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.6% from the previous month, equivalent to an annual increase of 4.7%.

in its latest Polls Among major company CEOs, the Business Roundtable found that rising wage costs due to labor shortages has become a top concern for CEOs, far outweighing issues such as supply chain disruptions or rising material costs.

“This is a tight labor market and it takes a lot of ingenuity, creativity and hard work to do everything we can to attract and retain employees,” ConAgra CEO Sean Connolly told analysts this week. “I feel good about where we’re sitting right now, but there’s no denying it’s a daily grind.”

data distortion

Economists also recognize that preliminary estimates of overall job growth could be significantly revised due to future reports. difficulty Economic measurement during a pandemic.

Salary figures for December will be updated in February and again in March. This figure is likely an underestimate; upward revisions add more than 1 million jobs over the course of 2021—a new single-year high.

Measuring payroll during a pandemic is especially challenging for two main reasons. First, businesses have been slow to respond to business surveys from which payroll estimates are derived, meaning that preliminary estimates are based on incomplete data.

In December, 71% of businesses responded by the deadline, compared to 81.5% in December 2019. Economists say businesses with the most activity, such as those with the fastest hiring, are likely to be among the slowest to respond, contributing to the initial underestimation of the payroll.

Second, the pandemic disrupts seasonal patterns, complicating the statistical models that BLS uses to strip out seasonal effects (such as vacation hiring) from raw data.

In December, raw data showed wage increases of 72,000, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics adjusted upwards by 127,000. This is smaller than a typical December adjustment, according to Gregory Darko, chief US economist at Oxford Economics. As the data comes in, so does the seasonally adjusted model, which will lead to more corrections.

[ad_2]

Source link