[ad_1]

According to a study Bovell-Ammon et al. (2021) In JAMA Open, the answer is yes. The authors used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), which tracked a nationally representative cohort of non-institutionalized youth aged 15-22 between 1979 and 2018. The authors used cumulative incidence function estimates to compare black and non-black incarceration. Since a higher mortality rate may reduce the chance of an individual being imprisoned, the cumulative incidence function explains the competitive risk of death to produce an unadjusted cumulative exposure curve for imprisonment; use gray nonparametric tests to test differences between groups by race .

Unsurprisingly, blacks are more likely to be imprisoned. Between the ages of 22 and 50, 11.5% of blacks are imprisoned (1 in 9 blacks are imprisoned), compared with 2.5% of non-blacks (1 in 40 non-blacks are imprisoned). Imprisonment).

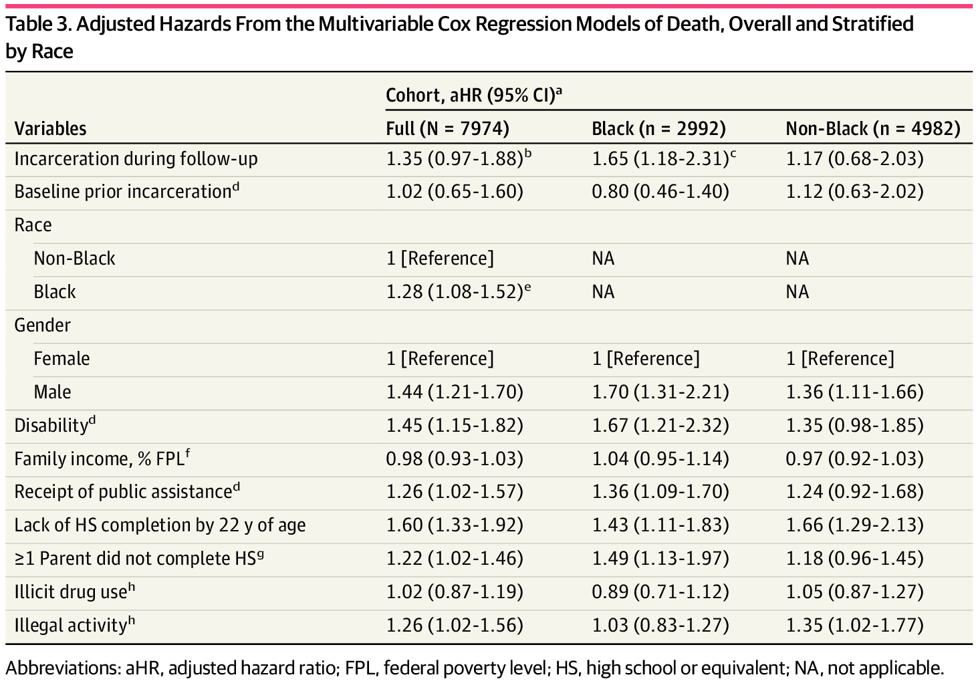

The author then checked whether the higher imprisonment rate would affect the mortality rate. Individuals who are imprisoned may be different from those who have not been imprisoned for reasons that may be related to imprisonment rates and mortality (for example, gender, education, parental income). In order to solve this problem, the author controls the individual’s gender, parental education, the acceptance of government welfare assistance, and the total family income. The authors then used the Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the impact of these factors and imprisonment on mortality.

The author found that imprisonment had a significant effect on the mortality rate of blacks, but had no effect on non-blacks.

In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model with a complete cohort, incarceration exposure over time is associated with increased mortality (adjusted HR [aHR], 1.35; 95% CI, 0.97-1.88), the results were not statistically significant. In the racially stratified model, imprisonment was significantly associated with increased mortality in black participants (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.18-2.31), but was not associated with mortality in non-black participants (aHR, 1.17; 95 % CI, 0.68-2.03).

editorial Sykes et al. (2021)However, these findings are indeed questioned. As I mentioned above, people who are imprisoned may be different from those who have not been imprisoned for many reasons. This will affect the imprisonment rate and death rate.although Bovell-Ammon et al. (2021) To control some observable factors (such as race, parental education, and family benefits), there may still be unobservable factors that have not been taken into consideration. Sykes and co-authors wrote:

For example, given that people at risk of being detained and imprisoned may differ in observable and unobservable characteristics, what is the counterfactual of imprisonment? In the research of Ruch et al.,2 Youths who have not been sentenced to detention but are on probation (or in a non-custodial treatment program) may have more similar characteristics to youths in the juvenile justice system than non-custodial youths receiving health insurance. Similarly, people convicted but not imprisoned may be more like the sample of individuals imprisoned in NLSY79 than the non-incarcerated sample used by Bovell-Ammon et al. in the study as the comparison group.

Although Sykes pointed out that selection bias may mean that the mortality rate is overestimated, other factors may indicate that the Bovell-Ammon estimate is too low. For example,

Researchers have recently begun to study the ability of incarceration to accelerate the decline in physical and mental health usually associated with aging (or aging). Accelerated aging shows that people in incarceration generally exhibit biological health conditions that are older than their actual age and have abnormally early health problems. However, accelerated aging research mainly focuses on adult prisoners, and it is necessary to explore the aging consequences of imprisoned teenagers who are experiencing biological, psychological and social development.

In addition, Bovell-Ammon’s paper focused on young people in 1979, and did not consider the impact of the surge in prison population and possible changes in prison conditions in subsequent decades. Despite these limitations, this paper raises an important question that deserves more investigation.

[ad_2]

Source link