[ad_1]

Published at 9:00 a.m. on December 21, 2021 go through Josh Bivins

EPI 2021 ranking

The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a series of severe inequalities in American society. In addition to emphasizing these inequalities, EPI’s research over the past year has also identified the distinctive features of intentional policy decisions in promoting inequality.

Building a better and fairer economy after a pandemic will require a fundamental repositioning of economic policy in many ways. Although 2021 has made a good start in some repositioning, there is still much work to be done. Below is the chart we selected as the best chart for 2021.

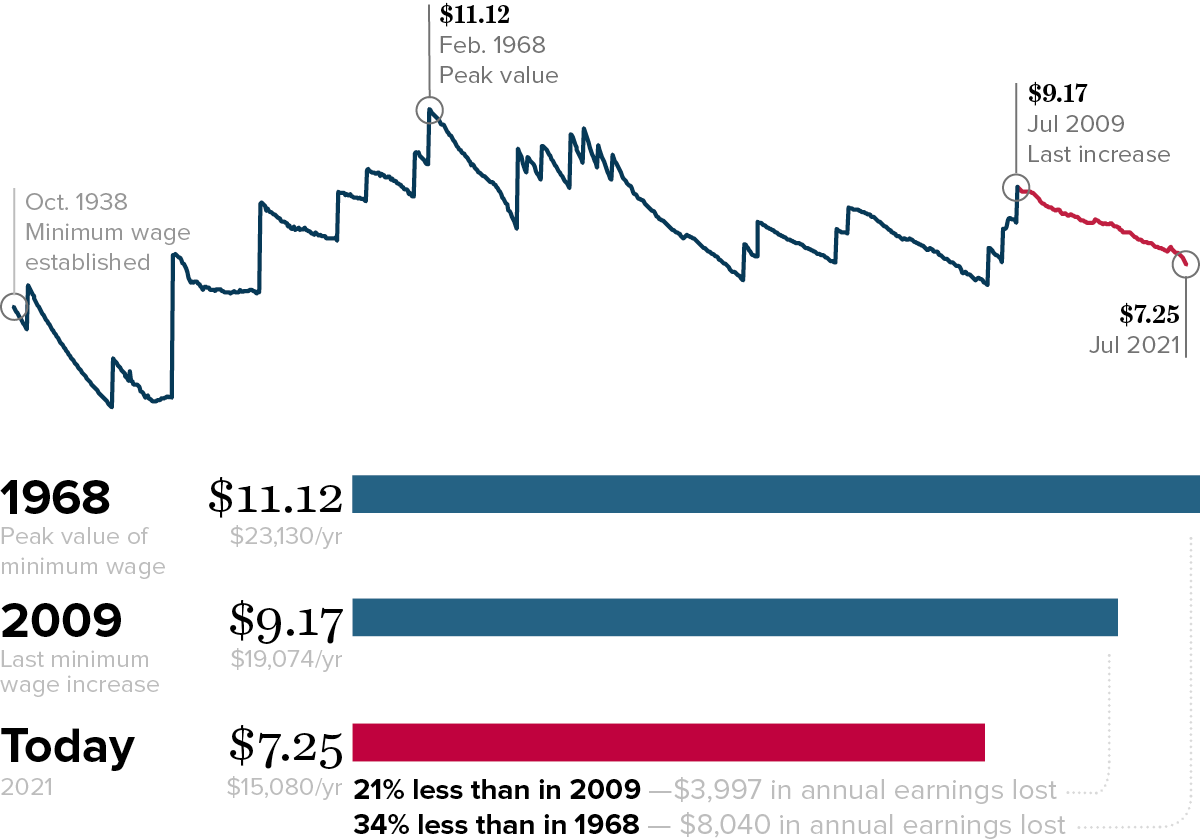

After experiencing the longest period of no growth in history, today’s federal minimum wage is 21% lower than it was 12 years ago and 34% lower than in 1968. : The actual value of the minimum wage (adjusted for inflation)

1

notes: All values ??are in June 2021 U.S. dollars, adjusted using CPI-U-RS

It has been 12 years since the last federal increase in the minimum wage on July 24, 2009. This is the longest period in the history of the United States without an increase. At the same time, the rising cost of living has weakened the purchasing power of the minimum wage. After adjusting for inflation, workers who pay the federal minimum of $7.25 today have real incomes 21% lower than their peers 12 years ago.

Share this chart:

In a pandemic recession, some population groups are more likely to work remotely than others: Proportion of employed persons working remotely according to specific demographics from May 2020 to April 2021

2

| Group value | share_tw_emp |

|---|---|

| Total, 16 years old and above | 24.27% |

| By age category”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | |

| 16 to 24 years old | 11.07% |

| 25 to 54 years old | 27.30% |

| 55 years old and above | 22.90% |

| By gender”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | |

| man | 22.1% |

| female | 27.9% |

| By race/ethnicity”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | |

| White | 25.89% |

| Black | 20.42% |

| Hispanic | 15.19% |

| Application program interface | 39.20% |

| By Citizen”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | |

| Not a U.S. citizen | 18.81% |

| U.S. citizens | 24.76% |

| By education level”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | |

| Below high school | 3.06% |

| Middle school | 8.12% |

| A university | 15.70% |

| University | 38.42% |

| advanced | 51.58% |

The data behind the graph.

notes: Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive (ie, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic of any race). AAPI includes Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

The proportion of workers working remotely due to COVID-19 has exposed not only differences in education levels, but also differences in age group, gender, race/ethnicity, and citizenship status. This figure shows that young workers have the worst ability to work from home, which is not surprising, because they tend to engage in face-to-face work and are more unemployed. In a pandemic, women are more likely to work remotely than men. As in the pre-pandemic period, the proportion of black and Hispanic workers who are able to work remotely still differs greatly compared to white and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) workers.

Share this chart:

Continued low unemployment will help narrow the wage gap between blacks and whites: The median wage gap between blacks and whites in actual and three counterfactual scenarios from 1973 to 2019

3

| Actual | 1.0 ppt.Lower average unemployment rate | 1.5 ppt.Lower average unemployment rate | 2.0 ppt.Lower average unemployment rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 28.6% | 28.6% | 28.6% | 28.6% |

| 1974 | 24.8% | 24.5% | 24.3% | 24.2% |

| 1975 | 23.7% | 23.1% | 22.8% | 22.5% |

| 1976 | 23.4% | 22.5% | 22.0% | 21.6% |

| 1977 | 23.2% | 22.0% | 21.4% | 20.8% |

| 1978 | 25.1% | 23.6% | 22.9% | 22.1% |

| 1979 | 19.6% | 17.9% | 17.1% | 16.3% |

| in 1980 | 20.9% | 18.9% | 17.9% | 16.9% |

| 1981 | 21.1% | 18.8% | 17.6% | 16.5% |

| 1982 | 24.0% | 21.3% | 19.9% | 18.6% |

| 1983 | 22.5% | 19.5% | 18.1% | 16.6% |

| 1984 | 24.2% | 20.9% | 19.3% | 17.7% |

| 1985 | 23.9% | 20.3% | 18.5% | 16.8% |

| 1986 | 24.9% | 21.0% | 19.1% | 17.2% |

| year 1987 | 24.4% | 20.2% | 18.1% | 16.1% |

| 1988 | 22.5% | 18.1% | 16.0% | 13.9% |

| in 1989 | 25.6% | 20.7% | 18.4% | 16.1% |

| 1990 | 25.2% | 20.0% | 17.6% | 15.2% |

| year 1991 | 28.4% | 22.8% | 20.1% | 17.5% |

| 1992 | 25.8% | 20.0% | 17.2% | 14.5% |

| 1993 | 24.8% | 18.7% | 15.9% | 13.1% |

| year 1994 | 25.1% | 18.8% | 15.8% | 12.8% |

| the year 1995 | 26.3% | 19.6% | 16.4% | 13.3% |

| year 1996 | 27.8% | 20.7% | 17.3% | 14.1% |

| 1997 | 27.3% | 20.0% | 16.5% | 13.1% |

| 1998 | 25.6% | 18.0% | 14.5% | 11.1% |

| Year 1999 | 24.4% | 16.7% | 13.0% | 9.5% |

| 2000’s | 26.2% | 18.0% | 14.2% | 10.5% |

| 2001 | 29.3% | 20.6% | 16.5% | 12.6% |

| year 2002 | 27.1% | 18.3% | 14.1% | 10.2% |

| Year 2003 | 25.3% | 16.3% | 12.1% | 8.1% |

| year 2004 | 24.8% | 15.6% | 11.3% | 7.2% |

| 2005 | 26.7% | 17.1% | 12.6% | 8.3% |

| year 2006 | 25.9% | 16.1% | 11.5% | 7.1% |

| 2007 | 28.7% | 18.3% | 13.4% | 8.8% |

| Year 2008 | 30.0% | 19.2% | 14.2% | 9.4% |

| Year 2009 | 27.1% | 16.3% | 11.3% | 6.5% |

| year 2010 | 26.9% | 15.8% | 10.7% | 5.8% |

| year 2011 | 28.5% | 16.9% | 11.6% | 6.6% |

| 2012 | 32.7% | 20.4% | 14.8% | 9.4% |

| year 2013 | 29.1% | 16.9% | 11.3% | 6.0% |

| Year 2014 | 31.8% | 19.0% | 13.2% | 7.6% |

| 2015 | 34.4% | 21.1% | 15.0% | 9.2% |

| 2016 | 29.8% | 16.6% | 10.6% | 5.0% |

| 2017 | 33.8% | 20.0% | 13.7% | 7.7% |

| 2018 | 36.4% | 22.0% | 15.4% | 9.2% |

| 2019 year | 32.2% | 18.0% | 11.5% | 5.4% |

The data behind the graph.

notes: The wage gap refers to how much the median hourly wage of black workers is lower than that of white workers.

Achieving and maintaining a high-pressure labor market since the early 1970s will greatly reduce the median wage gap between blacks and whites. If the unemployment rate decreased by an average of 2 percentage points over the entire period, the 80% of the median wage gap between blacks and whites that appeared in 1973 could have been eliminated (because the gap narrowed from 28.6% to 5.4%). On the contrary, the gap widened to 32.2%. Since the unemployment rate has fallen by only 1 percentage point on average, the median wage gap may drop to 18.0%. In short, the high-pressure labor market—the very low unemployment rate and rapid employment growth that occur when the Fed prioritizes low unemployment rates—has great potential for special measures to reduce this racial inequality in the labor market. .

Share this chart:

Due to policy errors, salary growth lags behind productivity growth: The contribution of various factors to productivity (in 2017 dollars)-the median salary difference from 1979 to 2017

4

| year | can not explain** | Non-competition, misclassification, overtime, supply chain advantage* | Corporate globalization | Eroded collective bargaining | Excessive unemployment | Real growth | Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD | 20.48 USD |

| 2017 | 33.10 USD | 30.72 USD | 28.59 USD | 27.30 USD | USD 25.46 | USD 23.15 | 20.48 USD |

The data behind the graph.

notes: Automation/skills defects have no effect.

* Leading buyers and fission

** Including but not limited to: wage theft, guest worker programs, racial discrimination, industry deregulation, mandatory arbitration and anti-poaching agreements

If the median hourly wage has increased with productivity growth since 1979, they will be at least $10 higher than they are now. This figure shows that excessive unemployment, erosion of collective bargaining, and enterprise-driven globalization are the key factors that restrained wage growth in the past 40 years. Together, these factors reduced the median hourly salary increase relative to net productivity growth by $5.45—accounting for 54.7% of the difference between productivity and salary from 1979 to 2017. Without these factors, the median hourly salary would rise to $28.59 instead of $23.15.

Share this chart:

Caregivers are a disproportionate number of women of color: Gender and race/ethnic classification of all workers, family health workers, and child health workers

5

| man | White women | Black women | Hispanic women | Asian-Pacific women | Women of other races/ethnicities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All workers | 53.1% | 29.1% | 6.4% | 7.5% | 3.3% | 0.5% |

| Nursing Staff”,”labelcolor”:”black”,”labely”:”8″}”> | ||||||

| Home health worker | 11.4% | 34.0% | 26.1% | 20.1% | 7.0% | 1.4% |

| Childcare worker | 6.0% | 53.1% | 14.1% | 22.3% | 3.3% | 1.2% |

The data behind the graph.

notes: To ensure a sufficient sample size, this figure comes from the micro data collected from 2018 to 2020. AAPI refers to Asian American/Pacific Islander. Race/ethnicity categories are mutually exclusive (ie, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, AAPI non-Hispanic, and Hispanic any race).

Nursing staff are severely undervalued and low paid. This figure shows that black, Hispanic, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women are more likely to become home health workers than their share of the labor force. In particular, relative to their share of the total labor force, black women are more than four times more likely to become family health workers. White, black, and Hispanic women are disproportionately represented in the childcare workforce.

Share this chart:

Sign up for EPI’s newsletter so you don’t miss our research and insights on how to make the economy better for everyone.

[ad_2]

Source link