[ad_1]

Authors: Chiara Burlina, Assistant Professor of Applied Economics, University of Padua, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Chair of Asturias Princess School, London School of Economics and Professor of Economic Geography; CEPR Fellow. Originally published on VoxEU.

Western countries are facing a “lonely epidemic.” Although its impact on mental health has attracted considerable attention, little is known about its economic impact. This column distinguishes two forms of loneliness—loneliness and living alone—and examines their impact on local economic performance in Europe. An increasing number of people living alone is driving economic growth, and increased loneliness can have devastating economic consequences. Although this relationship is complex and non-linear, regions with more populations will experience lower overall economic growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of loneliness in modern society (Smith and Lim 2020). Loneliness usually occurs “when a person believes that one’s social relationships are lower than expected in quantity, especially in quality” (Encyclopedia Britannica 2021). In this case, loneliness can be equated with loneliness—a distressing experience that can lead to increased irritability, depression, and premature death (Cacioppo and Cacioppo 2018).

Loneliness can also refer to people who live alone, without the company of family and friends. Living alone usually lacks the negative connotations associated with loneliness (Kurutz 2012). More and more people live alone not because of being forced but by choice (Wilkinson 2014). In the so-called “second demographic transition” (Van De Kaa 1987), the typical characteristics of elderly citizens living alone are replaced by adult professionals (usually women) with high education levels and stable employment. However, during the current Covid pandemic, which is characterized by mandatory or self-isolation, life satisfaction of people living alone may decline (Hamermesh 2020). This may have an impact on overall economic activity.

Generally speaking, loneliness and living alone describe different mental states, which can represent different attitudes to life and lead to different overall economic results. Factors such as increased female participation in the labor force, increased life expectancy, and urbanization are driving more and more people to live alone. Therefore, the proportion of people living alone has been rising for some time (Sandström and Karlsson, 2019). But living alone does not necessarily mean that the individual is alone. Lonely people often feel isolated, indicating emotional separation from others and society, while many people who live alone lack this emotional separation and lead a vibrant social life. They often make up for the lack of face-to-face interaction within the family through extensive interpersonal face-to-face and digital relationships.

When they are combined, from a purely economic point of view, these two dimensions of loneliness may have an adverse effect. First, more people feeling lonely and/or living alone may reduce the number of interpersonal and face-to-face interactions that are at the core of the development of new ideas and innovations (Storper and Venables 2004). Second, many people affected by loneliness may avoid engaging in economic activities. Third, different forms of loneliness may undermine trust and prevent the formation of social capital, which has been identified as an important factor in regional economic growth (Muringani et al., 2021). However, living alone is costly, and people living alone need a lot of economic resources to pay for the cost of real estate and rent. This may to some extent offset the potential negative economic impact of increased loneliness in developed countries.

Loneliness and living alone and economic growth

We investigated the impact of living alone and loneliness on the economic growth of 139 European regions in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic (Burlina and Rodriguez-Pose 2021). Our research considers three main measures of loneliness: the proportion of the population living alone in the total population; the social index as a representative of loneliness covers the degree of interaction within a region, measured by the number of face-to-face meetings for social purposes, regardless of frequency ; And the frequency of personal interaction (from daily social meetings to never meeting with other people for social purposes).

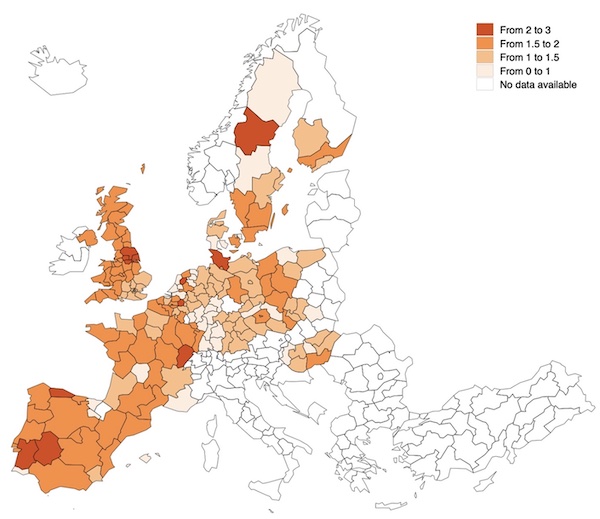

These different forms of solitary European geography are very diverse. Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of (a) the proportion of individuals living alone and (b) the social index. The proportion of people living alone in the Nordic countries and Central Europe is much higher than that of Iberia and Eastern Europe. National boundaries are clearly visible, and there is a clear gap between urban and rural areas.

The social/lonely geographic environment is more complicated. Southern countries such as Spain and Portugal have a higher degree of social interaction. But other countries such as France, the United Kingdom, and Sweden also show a high degree of social skills. There are large regional differences within the country-for example, the social differences between Schleswig-Holstein and Baden-Württemberg-and there is no clearly distinguishable urban/rural, urban/ Town mode. Many areas with a high concentration of people living alone—such as Brussels, most of the United Kingdom, Franche-Comté in France, or Schleswig-Holstein in Germany—also have a high social index.

figure 1 The proportion of the population living alone and the social index

Panel a

Group b

Social drives growth, but the relationship between loneliness and growth is more complicated

Although the rise of loneliness may cause harm to health, mental health, and society, from an economic point of view, it does not pose the same threat. More people living alone will help promote economic growth throughout Europe. More and more people choose to live alone — rather than being forced by the external environment — to promote economic growth, provided that they remain active in the workforce and are willing to establish contact and interaction with others.

In contrast, the increase in loneliness has had devastating consequences for the overall economy. A society where more people feel lonely is more limited in its ability to create additional wealth. However, the link between loneliness and economic growth depends on factors such as the frequency of meetings between people. Too much interaction, such as the prevalence of daily meetings, can undermine the benefits of face-to-face communication. A society where a large number of individuals meet weekly is also unlikely to develop. The “sweet spot” seems to be the majority of the population who meets with friends, relatives, and colleagues on average every week.

COVID-19 is bound to accelerate the rise of different forms of loneliness (Hamermesh 2020, Belot et al., 2020), so more policies are needed to mitigate its negative effects. It is not always clear how the government and administration should intervene in areas belonging to the personal realm; any form of loneliness may be the result of personal choice. However, the economic consequences of increasing loneliness can be felt not only at the individual level, but also at the overall level. This fact requires more policy considerations. In some countries, policies such as promoting choices when living alone are already on the table. In order to combat the “loneliness epidemic”, more intervention may be needed. In any case, finding solutions requires addressing the root causes of increasing loneliness in order to prevent or minimize its negative effects on collective health, well-being, society and the economy.

[ad_2]

Source link