[ad_1]

At the beginning of October, when most of China shuts down for the Golden Week holidays, the factories run by Apple’s most important suppliers usually go into overdrive. This is the week when Foxconn, Pegatron and others ramp up production to 24 hours a day, employing shift after shift of workers to pump out newly launched models of Apple’s iPhone in time to capture holiday season demand.

But it was different this year: workers got time off, not overtime.

For the first time in more than a decade, iPhone and iPad assembly was halted for several days because of supply chain constraints and restrictions on the use of power in China, multiple sources with knowledge of the situation told Nikkei.

“Due to limited components and chips, it made no sense to work overtime on holidays and give extra pay for front-line workers,” a supply chain manager involved told Nikkei Asia. “That has never happened before. The Chinese golden holiday in the past was always the most hustling time when all of the assemblers were gearing up for production.”

After launching the iPhone 13 range and new iPads in September, Apple is falling millions of units short of its production goals and missing out on billions of dollars of revenue. In many countries, it is now too late for consumers to buy some Apple products in time to give as holiday gifts.

This article is from Nikkei Asia, a global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective on politics, the economy, business and international affairs. Our own correspondents and outside commentators from around the world share their views on Asia, while our Asia300 section provides in-depth coverage of 300 of the biggest and fastest-growing listed companies from 11 economies outside Japan.

The company may be the envy of the consumer electronics industry and the world’s top procurement power, churning out over 200m iPhones, 20m MacBooks, 50m iPads and more than 70m pairs of AirPods annually, but even Apple has been chastened by the chaos in the supply chain this year. In the midst of its peak selling season, it is having a nightmare before Christmas. It is an acute example of the wider havoc wrought by supply chain problems on consumer goods companies worldwide. A combination of pandemic factory lockdowns, logistics troubles and energy generation squeezes has battered the globalised production model that has long powered modern manufacturing.

Through interviews with more than 20 industry executives across three continents and tracing the components inside the new iPhone 13 Pro Max, Nikkei has pieced together some of the unprecedented challenges facing Apple. It adds up to a portrait of an electronics supply chain in a period of turmoil, with problems that have their origins before the Covid-19 pandemic, in the tensions between the US and China over critical technology.

In September and October, production of the iPhone 13 range fell 20 per cent short of previous plans, people directly involved in its supply chain told Nikkei. This was even after Apple prioritised all the necessary components for the latest flagship smartphone — the company’s most important revenue source — at the expense of other products such as iPads and older generation devices such as the iPhone 12 and iPhone SE.

Over the same period, the reallocation of the shared components squeezed iPad assembly even more, leading to about 50 per cent less production volume than planned, while the production forecast for older generations of iPhones also dropped around 25 per cent, Nikkei heard from multiple sources. The situation for iPads and older iPhones was not much improved by November.

Apple was forced to scale back its total production goal for 2021, people briefed on the matter told Nikkei. At the beginning of December, the company was on course to make only about 83m to 85m units in the iPhone 13 range before the end of the year, falling short of the ambitious goal of up to 95m units that it had set to capture the first shopping season after western economies reopened from Covid-19 lockdowns. Overall, despite reaccelerating production in November, Apple was still falling about 15m units short of its aim to build 230m iPhones in total this year, an ambitious goal set at the beginning of 2021, sources said.

Apple declined to comment for this story.

The butterfly effect

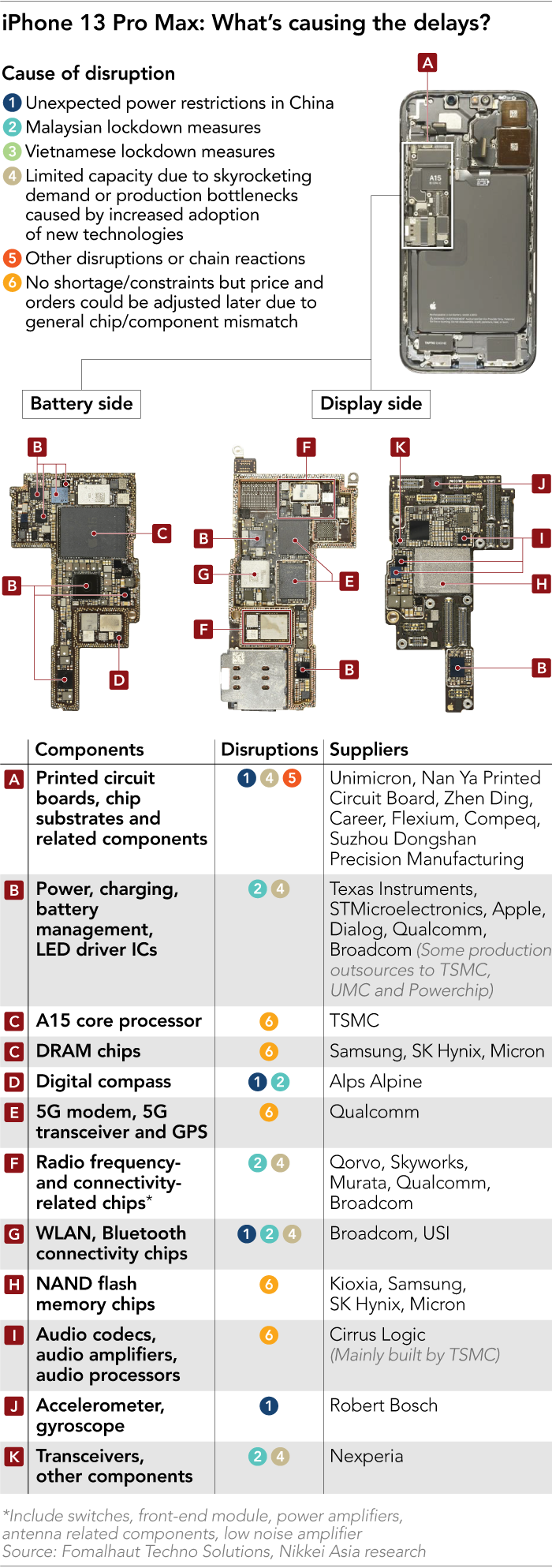

A look inside the iPhone 13 Pro Max, a complex electronic gadget with more than 2,000 components, reveals the difficulties.

Bottlenecks are not coming from production of the most expensive components like the $45 core processor, the A15, or the 5G modem that enables latest-generation wireless communication, or the premium organic light-emitting diode display that could cost up to $105 per unit.

Instead, the real headache comes from the tiny “peripheral” components that used to cost only a few cents and attract little attention, such as power management chips from Texas Instruments and transceivers from Nexperia as well as connectivity chips from Broadcom. Such chips are not unique to the iPhone, to smartphones or even to consumer electronics, but are used across computers, data centres, home appliances and connected cars.

“The entire semiconductor industry has been unable to meet this critical demand, also due to increasing lead times for raw material. This results in shortages for Nexperia, too,” a Nexperia representative told Nikkei, while declining to comment on Apple. TI and Broadcom did not respond to requests for comments as of publication.

Apple and its suppliers have faced a litany of problems. The months-long lockdown in Vietnam affected iPhone camera module production from Sharp, as Nikkei previously reported, which dragged out the timeline for final product assembly. Covid-19 disruptions in Malaysia weighed on production of many electronic components and chips. The south-east Asian country plays a pivotal role in chip packaging and testing — the final step of making chips. Unexpected restrictions on industrial power use in China piled on further misery.

“Even if you have 99 per cent of the components ready on hand, if you lack one or two or three components, it is not possible to kick off the final assembly of the product,” an executive at a top Apple supplier told Nikkei.

The year 2021 was shaping up to be a strong one for Apple, as it sought to grab market share from Huawei Technologies, whose premium smartphone business was seriously dented after the US imposed sanctions that have blocked it from obtaining critical components. In the first nine months of the year, iPhone shipments grew nearly 30 per cent over 2020.

But the headwinds kept intensifying. Apple chief executive Tim Cook, who is known for his expertise in building and operating the world’s most comprehensive supply chain, acknowledged that supply constraints cost Apple between $3bn-$4bn in lost revenue in the April-June quarter and another $6bn in the July-September quarter. He forecasts an even larger effect on this year’s final quarter. The scale of the hit will be revealed in Apple’s next financial results, which are due around the end of January.

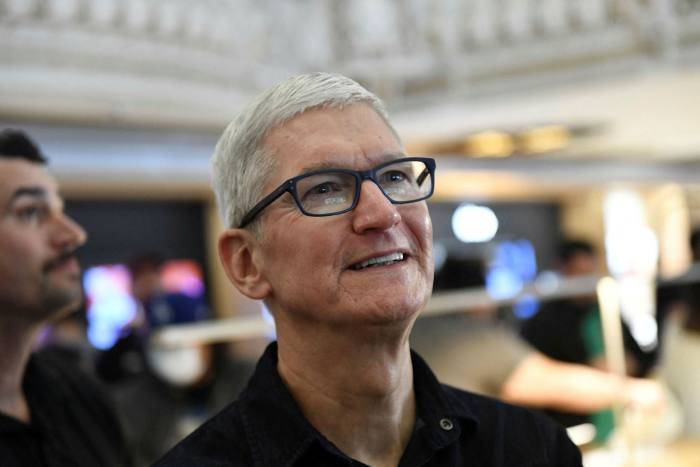

Consumers across the globe will probably miss the Christmas window if they placed an order for a new iPad in the second week of December, with delivery times already extended to mid-to-late January, according to Apple’s website. For the iPhone 13 Pro and 13 Pro Max, the waiting time has shortened to one to two weeks, from up to five weeks less than a month ago.

Empty stockings all round

If even the mighty Apple is suffering, the effect from the unprecedented turmoil in the supply chain cuts even deeper at other electronics companies, from top smartphone makers Samsung Electronics, Xiaomi and Oppo, through to PC makers such as HP, Dell Technologies and Acer, as well as game console makers Sony Group and Nintendo and home appliance builders such as Dyson and LG Electronics. To varying extents, all have been unable to produce enough products and deliver them in time for the year-end holiday season, according to Nikkei interviews with more than 20 industry and supply chain executives.

Nintendo, for instance, is 20 per cent short of the original production plan for its Switch game console this fiscal year through March, Nikkei first reported in November. Xiaomi said chip supply constraints hit its smartphone shipments for this year to the tune of 20m units. A big fear in the industry is that demand could dissipate after missing the holiday season sales window.

The chip shortage has sown disorder in all corners of global manufacturing, upending the car industry’s famously lean supply chain and threatening defence equipment supplies to the extent it became a national security concern. Manufacturing shortfalls have affected economic growth, while product shortages have sent inflation soaring in many countries.

Jason Chen, chair and chief executive of Acer, the world’s fourth largest PC maker, said he has never seen such challenges. “Christmas holidays are not cancelled, but they are delayed [for the tech industry],” he said. “It’s not enough to have experience of working for decades in the industry. No one has had this experience before. None of us know how to handle such complicated challenges properly.”

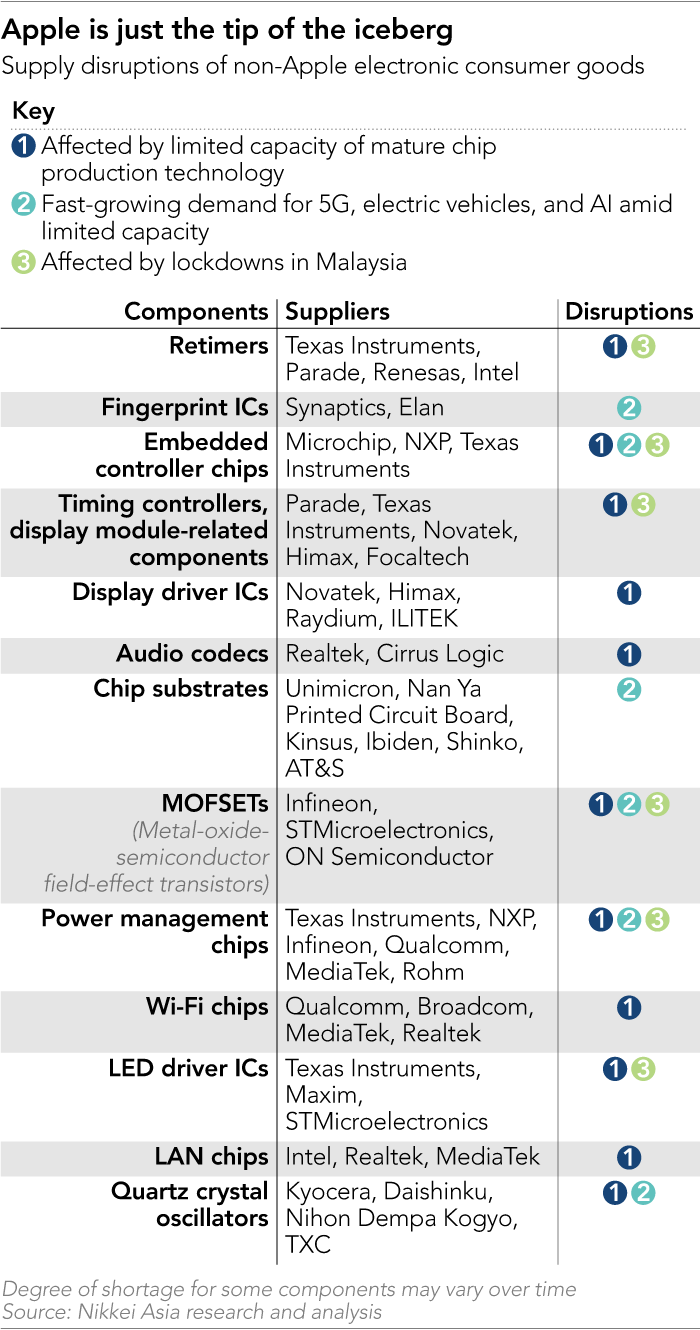

According to Nikkei’s interviews with executives at companies ranging from chip developers and module and electronics makers to distributors, the components that are creating bottlenecks across industries include power management chips, WiFi chips, LAN chips, crystal oscillators, diodes, microcontrollers, interface chips, audio chips and driver-integrated circuits, as well as materials like substrates on which chips are mounted. None of these chips are particularly advanced or core to devices, unlike central processors and graphic processors. But they are indispensable in building all kinds of electronic devices and cars.

“Life is really tough,” Emily Hong, chief executive of Wiwynn, a server and data centre builder for Meta, Microsoft and Amazon. “There are 4,000 components on a server printed circuit board?.?.?.?even if we’ve reacted quickly to redesign and look for alternatives, problems are coming up one after another.”

For those who do not have Apple and Samsung’s massive procurement prowess or ship in billions of gadgets, the chip supply crunch poses even direr challenges. With less bargaining power, many face being bumped to the back of the queue.

“We talk with our suppliers constantly. But compared with smartphones and PC makers with massive volume for general consumers, industrial computers have a lower priority to secure the supply. Sometimes suppliers have chips on hand, but they just can’t give them to us first,” said Miller Chang, president of the embedded IoT business at Advantech, the world’s biggest industrial computer maker and a supplier to Samsung, Siemens, Philips and General Electric. “The thing was our $1,000 industrial computer systems could not be shipped and are stuck for the lack of some components that cost less than $1.”

Several industry executives expressed particular frustration with so-called integrated device manufacturers. These are big semiconductor companies that operate like department stores, supplying all types of high-quality peripheral chips, from power management chips and microcontrollers to sensors serving different functions. Products from such companies — Texas Instruments, NXP Semiconductors, Nexperia and STMicroelectronics among them — are not only widely used in consumer electronics, but also in industrial, aerospace, automotive and medical applications. They are also vital suppliers of chips that go into Apple’s iPhones, iPads, Macs and watches. Many of these companies’ chip packaging and testing facilities were disrupted during Covid-19 lockdowns in south-east Asia, on top of snowstorms in Texas and earthquakes in Japan in the past year.

And they have had procurement issues of their own. As well as manufacturing and packaging chips in-house, they often outsource older chips to contract manufacturers such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing, United Microelectronics Corp and GlobalFoundries for cost-reduction purposes. But they typically do not have priority at their outsourcing partners compared with Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices, who design their own chips and outsource 100 per cent of their production.

STMicroelectronics said in a recent earnings call that one of the largest challenges in the July-September quarter was the worse than anticipated Covid-19 situation in Malaysia, as a result of which its site went through periods of partial or complete closure.

Pre-pandemic warning signs

Shortages that are sometimes blamed solely on the Covid-19 pandemic in fact have earlier origins, partly in the tensions between the US and China and Washington’s clampdown on China’s Huawei Technologies. The effect has been similar in some ways to the lines at gas stations when a hint comes that fuel may be running out.

Huawei began stockpiling critical components, from chips to optical parts, more than two years ago after chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou was arrested in December 2018 in Canada and the US put Huawei on its trade blacklist. Washington has labelled Huawei a security risk and tried to freeze it out of telecoms systems in the US and its allies. Huawei has denied the accusations.

That fear of being cut off from vital components and equipment supplies quickly spread through the Chinese tech industry and sparked a nationwide campaign to hoard inventories to survive any likely crackdown.

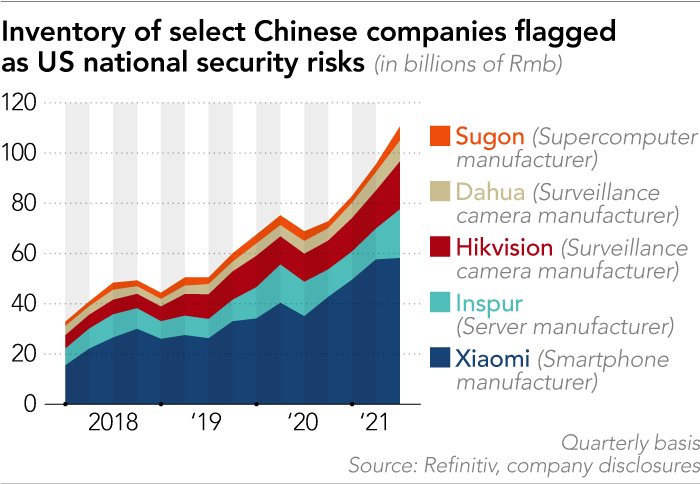

Nikkei tracked the financial statements of five large Chinese companies that have been blacklisted or flagged by the US for alleged links to China’s military, or for posing a national security risk: surveillance camera makers Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology and Dahua Technology, server manufacturers Inspur and Sugon, and smartphone maker Xiaomi.

Their cumulative inventory has risen every quarter since the March quarter of 2018, after the US threatened to impose higher tariffs and subsequently banned China’s leading telecom gear provider ZTE from using American tech in April of the same year. The inventory had more than tripled to a record Rmb110bn ($17.3bn) by the July-September quarter of this year.

Through 2019 and 2020, the US placed about 150 Chinese companies, research organisations and universities on the so-called Entity List to limit their access to American technologies, according to Nikkei’s analysis of US Federal Register documents.

In 2020, Washington blacklisted China’s largest contract chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp, limiting its ability to acquire advanced chip production tools, a sector dominated by a handful of American companies. The move to restrict SMIC created disruptions and uncertainties over the continuity of supplies and customers rushed to place orders at SMIC’s competitors to avoid being affected. Later, they rushed back to the Chinese chipmaker as the global chip shortage worsened.

The inventories of China’s top two chip manufacturers, SMIC and Hua Hong Semiconductor, had increased by 58 per cent and 292 per cent respectively by the July-September quarter of this year from March 2018. SMIC’s co-CEO recently confirmed that more Chinese clients were eager to have “indigenous production” to boost their supply chain resilience, curbing their reliance on foreign tech.

“The question should be: Who is not stockpiling more components?” said Donnie Teng, a tech analyst with Nomura Securities. “If they are not doing so, that could mean life or death for a company if they face sudden geopolitical shocks.”

Pandemic pressures

The outbreak of Covid-19 changed human behaviour and reshaped demand across consumer electronics. Working, studying and entertaining oneself at home created the need for new TVs, notebooks, monitors, tablets, fitness equipment and game consoles, as well as bolstering the adoption of faster 5G connectivity and larger storage. The PC industry, which had endured slowing demand for a decade, last year enjoyed a 13 per cent surge in global shipments, while the tablet market also returned to growth and extended the momentum into the first three quarters of this year.

The jolt occurred at the same time several other structural shifts were intensifying, including the shift toward electric vehicles and the widespread adoption of 5G, artificial intelligence and high-performance computing. As these technologies began to take off, so too did the consumption of chips and components. A constrained and disrupted supply chain simply could not keep up.

A year ago, many chip sector executives were looking at capacity that had been fully booked at least through the end of 2021 and calling it a “happy problem”. But it quickly turned sour and became a yearlong supply chain management nightmare.

“Today one component is in shortage, tomorrow another component hits some other issues. The disruptions could happen in different geographical regions of Vietnam, Malaysia, China and other places,” a senior manager at Intel told Nikkei. “In the past, we only needed to sell chips, but now we need to handle all the SOS queries from our device maker customers to see if we can help them resolve some of their bottlenecks, given that we are more familiar with the chip supply chain than them.”

The recovery of the automobile industry since the last quarter of 2020 further weighed on the already-tight supply of semiconductors and components — and governments’ responses added new complexity.

With manufacturers such as Ford, Nissan, Toyota and BMW cutting production by millions of cars and furloughing workers, the shortages were elevated to national security level. The US, Japan and Germany began pressuring global chipmakers to increase production and prioritise their supplies to automobile makers.

But as governments tried to muscle their automakers to the front of the queue, the planned chip and component supplies to other areas came under threat, prompting another round of panic buying. Procurement managers resorted to “double or triple booking”, placing orders at multiple suppliers at the same time.

That, in turn, has pushed the lead time for many chips — microcontrollers, power management chips, WiFi chips — to more than 52 weeks and beyond, with the elongating timetable encouraging buyers to order more and more now to get ahead of the queue.

The price of these chips has increased 200 per cent, 300 per cent and in some cases 10 to 20 times from less than $1. For those that find their way to the spot market, for immediate trading, the price can be even more.

“We have someone sit in front of the computer and check different websites to see if we can find some ‘spot’ goods,” said Devin Hsiao, chief financial officer at Transcend Information, a storage, multimedia and industrial solutions provider. “If we find that, we will take that. Once, we even quickly grabbed the phone and asked the bank to raise the credit card limit to bid for that. If we directly go to the chip supplier [like in the past], they would tell us the waiting time is at least 52 weeks.”

A rolling supply of setbacks

Apple has been spared such indignities. It has long enjoyed industry-wide priority for chip and component supplies, sources with direct knowledge told Nikkei. The company rarely agrees to pay more to secure materials, they said. “Most of the suppliers will do whatever they can to support Apple. Because if they do not do so, they risk losing Apple’s orders and allocations to their competitors the next time,” one source said.

With such strong purchasing power, Apple previously anticipated that this year would be smooth. It would start production by the end of August and launch its iPhone 13 series in the fall, in contrast with last year when Covid-19 disruptions caused months of shipment delays.

However, the Delta variant’s sudden surge in south-east Asia this summer — about two to three months ahead of Apple’s production ramp-up — caught the company off guard, stretching a 10,000-strong internal army of supply chain managers, engineers and procurement staff to the limit.

The army includes task forces to manage each type of material used in Apple products and each type of component, to negotiate prices with global suppliers, to ensure smooth deliveries, to oversee hardware manufacturing and quality and to conduct logistics planning.

“Since day one when Malaysia was planning another strict lockdown measure, Apple was on alert and started to calculate components that will be impacted and see how to mitigate the situation,” one source said. “But it’s hard to be immune.”

Malaysia controls about 13 per cent of global chip packaging and assembly capacity. Key chip and component makers Texas Instruments, STMicroelectronics, AMS, Murata Manufacturing, ON Semiconductor, Renesas Electronics, Rohm and Nexperia operate local facilities that directly supply Apple.

“For about two to three months since June, only 60 per cent or fewer employees are allowed to work,” a source familiar with the situation told Nikkei. “All of the non-essential manufacturing, except food and medicine, was even suspended for weeks. That seriously affected the output.”

Suppliers in Vietnam, where Apple sources many key components, such as the camera module for iPhones, were forced to suspend operations for almost two months, just when Apple was about to begin mass-producing the iPhone 13. The Vietnamese government required manufacturers that wanted to keep their factories open to have their workers sleep on-site to prevent the virus spreading.

“That’s an impossible request, especially for bigger companies with thousands of workers. No one could suddenly build dormitories that could house all employees on-site,” a local factory owner told Nikkei. “Some smaller companies could only set up temporary tents in yards or warehouses.” Suppliers gradually restarted their production in October, only to be hit with a new headache — a labour shortage. Workers who had been trapped in the city for months rushed back to their hometowns as soon as the lockdown was lifted.

Then in late September, with emissions surpassing environmental targets and coal prices soaring, China imposed restrictions on power use in key industrial provinces, including Guangdong and Jiangsu, where multiple Apple suppliers operate more than 150 manufacturing facilities for essential components from printed circuit boards to batteries, or offer printing and packaging services, according to a Nikkei analysis of Apple’s supplier list.

Many suppliers were notified only a day or even a couple of hours before their electricity supply was restricted for at least a week. Thousands of businesses scrambled to negotiate with local governments and communicate with clients, while trying to retain tens of thousands of workers for fear of a labour shortage when the electricity came back.

“We were talking to officials to check with the latest power supply policy, reviewing our stocks of each component and chips every day,” an executive at a top Apple supplier told Nikkei. “Apple also stepped in to help many of the smaller suppliers negotiate with local governments. It was like one headache comes after another [and] never ends.”

New year, same problems?

For many of Apple’s top suppliers, it has been a financially bruising year. Pegatron, an iPhone assembler, posted a net profit plunge of 60 per cent year on year in the July-September quarter, while smaller rival Luxshare Precision Industry, China’s top contract electronics manufacturer, reported net income down 25 per cent from a year earlier.

“The supply chain heavily relies on Vietnam and Malaysia and the impact of the disruptions was significant,” Pegatron chief executive SJ Liao told investors and reporters.

Taiwan’s Foxconn — the largest iPhone assembler and the world’s biggest contract manufacturer of electronics — posted strong July-September earnings, but warned it was not so sure about next year. It pointed to persisting global chip shortages, inflation and geopolitical dynamics.

Apple, however, is expected to continue to post handsome profits. The consensus of Wall Street forecasts is for a net profit of $30.8bn for the Christmas quarter, up 7 per cent from last year, despite losing out on billions in revenue.

What is likely to be more important to analysts and investors — and Apple’s share price performance — will be what Apple chief Cook predicts for the supply chain in 2022 and beyond.

An investment boom is under way across the global chip industry, fuelled by the effect of the shortages this year and fanned by governments’ determination to bring large parts of their tech supply chains onshore.

Capital spending on semiconductor equipment surged 34 per cent to a record $95.3bn for 2021 and will top $100bn for 2022, according to SEMI, a global chip industry association. The world’s top three chipmakers — Intel, TSMC and Samsung — have embarked on their most aggressive capacity expansion plans, promising to spend more than $350bn in the coming years to help alleviate the chip shortage. Top Chinese chipmaker SMIC, meanwhile, has pledged to triple its production capacity.

However, most of the new investments will not lead to mass production until 2023 at the earliest. More immediately, demand for some consumer electronic products has shown signs of slowing.

“We found the demand is slowing for TVs, Chromebooks, Bluetooth earbuds, IP cameras and Internet of Things devices,” said Huang Yee-wei, vice-president of Realtek Semiconductor, one of the world’s leading WiFi chip developers. “The consumer market in China is also slowing.”

Apple told suppliers to reaccelerate their production of the iPhone for November, December and January, after stumbling for the past few months, sources said. Communications in the past two days indicate that it hopes to get more than 5m units closer to its original goal than it expected at the beginning of December. “Demand for the iPhone 13 range should be able to extend until January next year, as Apple does not want to waste the opportunity to take more ground from Huawei, while Samsung and Xiaomi are suffering from chips and component mismatches,” said a source with direct knowledge of the conversations.

But after the Chinese Lunar New Year in February, production demand for new iPhones will decelerate and enter a traditional slow season, several sources with direct knowledge told Nikkei.

An executive at another iPhone component supplier told Nikkei that Apple was constantly reassuring them that demand persisted and that it was simply postponing some orders to a later period due to supply constraints. “But every month we see we are missing the shipment goal,” the executive said. “We are not sure if those missing volumes could eventually come back or would just disappear.”

Additional reporting by Shunsuke Tabeta in Beijing and Ryo Namiki in Tokyo.

A version of this article was first published by Nikkei Asia on December 8 2021. ©2021 Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved

Related stories

[ad_2]

Source link