[ad_1]

As Christine Lagarde unveiled plans last week to redesign euro banknotes for the first time since their launch two decades ago, the European Central Bank president said they were “a tangible and visible symbol that we stand together in Europe, particularly in times of crisis”.

Lagarde’s comment underlines her pride in the united approach taken by European nations and policymakers to tackle the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and — so far at least — prevent it from spiralling into a repeat of the region’s 2012 debt crisis, which threatened to tear the currency union apart.

However, the hardest challenge for the ECB still lies ahead. Having overseen the biggest injection of monetary stimulus in the history of Europe’s single currency, including the €2.2tn purchase of mostly government bonds and a similar amount of heavily subsidised loans to banks, the central bank is now preparing to start scaling back its support for the economy.

Most central banks have already started to withdraw the generous stimulus policies they introduced to lower borrowing costs and shield economies from the fallout of the pandemic. But the ECB — still scarred by criticism of having raised interest rates too soon in the last crisis — is more reluctant than most to wind back its support, having struggled until recently with years of uncomfortably low inflation and sluggish growth.

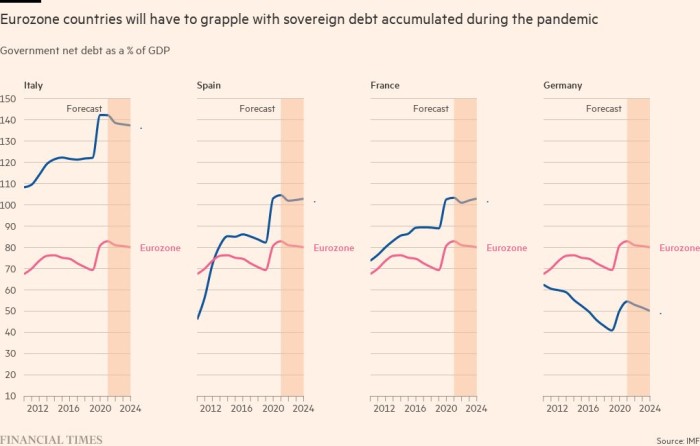

The eurozone has the added complication that unlike the US Federal Reserve or the Bank of England, the ECB has to make policies for 19 different countries, each with its own economy and — crucially — bond market. So any shift by the ECB to a less accommodative policy risks reawakening the region’s old financial tensions by pushing up financing costs for weaker governments — in particular Italy — and stifling its nascent economic rebound.

Managing the recovery phase requires a delicate balancing act by Lagarde and her fellow policymakers as they try to avoid the mistakes the ECB made when it prematurely raised interest rates in 2011 just as the region’s debt crisis was erupting.

However, if the ECB waits too long to reverse its stimulus it risks losing credibility and being forced into an even more painful policy correction later on. This could happen if inflation does not fall back below the bank’s main objective of 2 per cent as fast as it expects, having already hit a new eurozone record high of 4.9 per cent in November.

Most analysts expect the ECB to continue buying bonds and keep interest rates deep in negative territory at least until 2023, especially after it accepted in a strategy review that inflation could exceed its target for a period.

“This is crunch time for the ECB, because if they lose patience when inflation is about to peak, they risk undermining the conclusions of their strategy review and with that, the stability of the bond market,” says Frederik Ducrozet, strategist at Pictet Wealth Management.

Vítor Constâncio, a former vice-president of the ECB who is now finance professor at the University of Navarra in Madrid, says “the situation is becoming more difficult for the ECB”.

He adds: “The big question is how smoothly the ECB will prepare the aftermath of the pandemic and the gradual winding down of asset purchases.”

Covid complications

When the ECB meets on Thursday, Lagarde is expected to announce the first step in the process of slowly withdrawing its stimulus by outlining plans to end net bond purchases in March under the €1.85tn pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), which it launched when the virus hit last year.

Complicating its decision is the arrival of the more infectious Omicron coronavirus variant at a time when the Covid infection rate had already risen to new highs in many parts of Europe.

The return to varying levels of lockdown is expected to hit eurozone growth, which had been on track to recover from last year’s record postwar recession by the end of this year. At the same time, the latest wave of the virus is also likely to accentuate the supply chain bottlenecks that have already caused vast backlogs of containers at ports and steep increases in the prices of many goods — all of which could keep inflation higher for longer.

After eurozone economic output shrank by a record 6.5 per cent last year, the EU has forecast it will increase 5 per cent this year and 4.3 per cent next year — by far the highest levels of growth since the single currency was launched over 20 years ago. Brussels also predicts inflation in the bloc will stay above the ECB’s 2 per cent target for a second consecutive year in 2022 — the first time that will have happened for a decade.

The ECB is set to raise its own inflation forecasts this week, but it seems determined to avoid any sudden policy reversal. When the central bank slowed its bond purchases in September, Lagarde denied it was starting to “taper” them down to zero, echoing the late UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher by saying “the lady isn’t tapering”. This month she pledged to “ensure conditions remain favourable” for financing governments, households and firms and described the recent surge in inflation as a “hump” that would decline next year.

All this means the ECB looks increasingly like a “dovish” outlier compared to many central banks. In response to a stronger surge in inflation than they expected, the Fed and BoE are this week expected to signal they will stop asset purchases and prepare to raise interest rates in the next few months. In contrast, the ECB has indicated it expects to keep buying bonds for all of next year and Lagarde said it was “highly unlikely” to start raising interest rates before 2023 at the earliest.

Analysts expect the ECB to reduce the “cliff edge” in its bond-buying after the PEPP ends in March by ramping up an older quantitative easing scheme, which is still hoovering up €20bn of assets a month. It could do this by increasing monthly purchases under the older scheme to about €40bn or by adding an extra “envelope” of several hundred billion euros to spend over the rest of the year.

Some ECB executives have even suggested keeping an option open to restart the PEPP or creating a new “backstop fund” to deal with any market disruption. Others stress the need for “optionality” and hope to delay some decisions on future bond purchases until February.

“Given the ECB has made the mistake in the past of tightening too fast it is going to err on the side of caution this time,” says Maria Demertzis, deputy director of the think-tank Bruegel. “If they increase interest rates too fast that will create a direct threat of financial fragmentation while we are still in quite a vulnerable stage of recovery — the US and UK don’t have that concern.”

Many share Demertzis’s concern about financial fragmentation, whereby the borrowing costs of weaker eurozone countries could rise much higher than those of safer ones, which stems from the fundamental weakness at the heart of the single currency: it is a monetary union without a fiscal union or a fully unified banking system.

The same faultline was exposed in the region’s sovereign debt crisis when investor fears about high government debt levels and toxic bank loans pushed up borrowing costs for countries in Europe’s periphery and forced several of them to turn to the EU for bailouts, including Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal.

“What is different for the ECB compared to the Fed and the Bank of England is that there is a risk of financial fragmentation in the eurozone,” says Spyros Andreopoulos, senior European economist at BNP Paribas who used to work on monetary policy at the ECB. “It is not democratically legitimised to share large-scale financial risks by using its balance sheet.”

However, even though debt levels have again shot up to new highs across the eurozone, economists believe a similar crisis is less likely to happen this time. This is mainly because the EU now has a much more supportive fiscal position after launching a €800bn recovery fund. This innovative scheme enables Brussels to issue debt centrally and send the money to member states to boost their post-pandemic economic prospects by investing in new green energy and digital projects.

“Europe has more instruments now to address a situation like the one we faced a decade ago, so it will take a much bigger asymmetric shock to cause a similar crisis,” says Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, chair of French bank Société Générale who was on the ECB executive board until 2011.

Life after PEPP

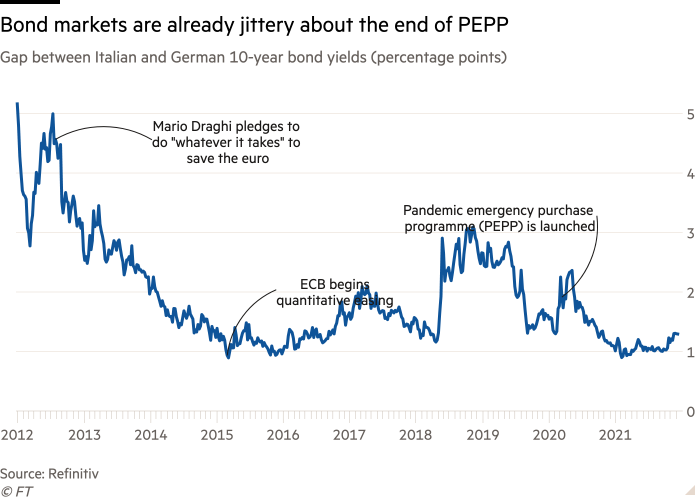

When the pandemic first hit last year, Lagarde got off to a stuttering start. Asked what the central bank could do to support governments as their economies shut down in March 2020, she said it was not the ECB’s job to “close spreads” — referring to the extra interest that weaker eurozone members have to pay relative to Germany when they sell new debt.

Her comment sent euro area bond markets into a tailspin. Investors suddenly doubted the ECB’s commitment to holding the eurozone together at a moment of crisis. Italy, by far the most indebted of the bloc’s big economies, bore the brunt of the bond sell-off.

The episode prompted a swift rethink. Lagarde quickly rowed back from the remarks and later that month the ECB unveiled the much larger PEPP. The rearguard action calmed the markets after a few weeks of volatility, and Italy’s bond yields sank for the rest of the year.

“Governments had to do massive fiscal stimulus,” says Salman Ahmed, head of strategic asset allocation at Fidelity International. “The role of the ECB was to make sure they could borrow at a rate that makes it affordable.”

But this role for asset purchases, even if it was never made explicit by the ECB, raises awkward questions as the central bank plots an exit from its pandemic-era stimulus, which has led the ECB to buy more than the total net debt issued by eurozone governments for the past two years.

Bond markets are already showing nerves over the prospect of life after PEPP. In recent days, the spread on Italy’s 10-year debt over that of Germany has reached its widest point in more than a year at 1.3 percentage points.

Despite investors’ positive perception of the Italian government — led by former ECB president Mario Draghi — Italy’s €2.3tn bond market remains the favoured playground for investors looking to speculate on renewed fragilities in the eurozone.

The biggest worry for some ECB-watchers is that Italy could be plunged back into political instability if Draghi steps up early next year to become president of Italy, which could trigger new elections that Eurosceptic rightwing parties, including Matteo Salvini’s League and the far-right Brothers of Italy, are favourites to win.

“There is the possibility of a Salvini government in coalition with the Brothers of Italy next year and that could be a big problem,” warned Constâncio, who was Draghi’s deputy at the ECB for seven years until 2018. “A mild increase in government bond yields is in general acceptable,” he said. “But if peripheral spreads move a lot higher the threat of financial fragmentation will require national and European policymakers to respond.”

The sheer size of Rome’s borrowing — amounting to more than 155 per cent of GDP — means a move above 2 percentage points on Italian spreads would reawaken concerns about debt sustainability, according to Ahmed. “It’s a huge credit risk without the backing of the ECB,” he says.

The other problem for Lagarde is that extra bond-buying is increasingly difficult to justify with inflation running well above target. Any sign that the more conservative “hawks” are gaining the upper hand could see investors once again question the ECB president’s commitment to controlling sovereign spreads.

“The market’s got into its head that it’s going to see additional purchases to replace PEPP,” says Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at BlueBay Asset Management. “If they don’t deliver that there’s a chance the spread in Italy will blow out again.”

Some investors worry Lagarde lacks the determination of Draghi, who in 2011 memorably promised to do “whatever it takes” to protect the euro. “You still have that comment [by Lagarde] from March last year ringing in the back of your mind,” says Dowding. “Market participants have a long memory and still don’t trust Lagarde in the way they trusted Draghi.”

The recent surge in inflation to levels not seen for more than 20 years has also fuelled rising criticism of the ECB, particularly in richer countries like Germany where its ultra-loose monetary policy has been subject to several legal challenges and suspicions it is supporting profligate southern governments at the expense of prudent northern savers.

Christian Lindner, the new German finance minister, said last week the government was “sensitive to avoid a situation of fiscal dominance in the future”, referring to the fear that the ECB could be unwilling to withdraw its stimulus due to a fear of pushing up borrowing costs for heavily indebted governments. “The central bank must also be able to respond to monetary developments with its instruments,” he added.

“Germans are getting increasingly nervous about rising prices,” says Klaus Adam, an economics professor at the University of Mannheim. “If inflation rates won’t ease in the next few months, as expected, the critics of ECB policy will get more vocal.”

Bild Zeitung, the top-selling German tabloid newspaper, warned recently that “prices are skyrocketing, our purchasing power is melting away”, and put the blame squarely on “Madame Inflation” — a reference to Lagarde.

Sentiment at the ECB also seems to be shifting against further large-scale bond buying, with Isabel Schnabel, the German board member responsible for market operations, last week arguing that it has pumped up the price of many assets, including residential housing, to dangerous levels and encouraged “excessive risk taking”.

But some investors think the central bank can still keep bond yields in check without having to commit upfront to buy hundreds of billions more in assets. Christian Kopf, head of fixed income at German asset manager Union Investment, says the ECB should announce a new programme that will intervene in markets only if there is a “dislocation”.

If investors think the central bank is lurking in the background they will be inclined to keep buying Italian and other lower-rated eurozone debt, doing the ECB’s heavy lifting for it. “The blanket QE approach is dying, and I think that’s a good thing,” says Kopf. “The ECB doesn’t need a permanent presence in markets, but the threat of a presence.”

“We hold a couple of billion of Italian bonds, and we are long-term holders,” he said. “If I have to factor in the risk of a self-reinforcing spiral I will be less comfortable holding that debt. But if I know there’s a circuit breaker I will be a lot more comfortable.”

Europe’s response to the pandemic has so far been more unified and potent than in previous crises, but the true test will be how it manages the recovery. On Thursday, the ECB will take the first tentative steps towards that objective and Lagarde will be hoping to bring investors along for the ride.

[ad_2]

Source link