[ad_1]

Two months ago, the world’s largest container ship “Ever Ace” arrived at the port of Felixstowe on the east coast of England on its maiden voyage. The ship carrying 23,992 containers took two months to climb from Qingdao in eastern China to Suffolk Port. It transports goods, including computers, games, clothes and food-and then picks up a large number of empty containers and transports it back to China.

These huge new ships require very large infrastructure, as the sister ship Ever Ace anchored in the Suez Canal earlier this year demonstrated. This may require expanding the docks where ships are anchored, dredging channels to provide access, as well as improving roads, heightening bridges and wider canals.

In Felixstowe, some berths have been expanded, and the local Harwich Haven Authority has begun to deepen the waterway at a cost of 120 million pounds by 2023.

However, if there is a clear need to adapt ports to new large ships before Covid-19, the supply chain congestion caused by the pandemic brings new urgency to the need for port modernization and automation.

“The pandemic shows us how fragile the supply chain is and how we fall behind [behind] Christian Roeloffs, CEO of Container xChange, said the company provides an online platform for the industry to buy, sell and lease containers.

Covid-19 border restrictions, social distancing requirements, and factory closures have all caused severe damage to the traditional supply chain, leading to soaring freight rates on major routes between China, the United States and Europe.

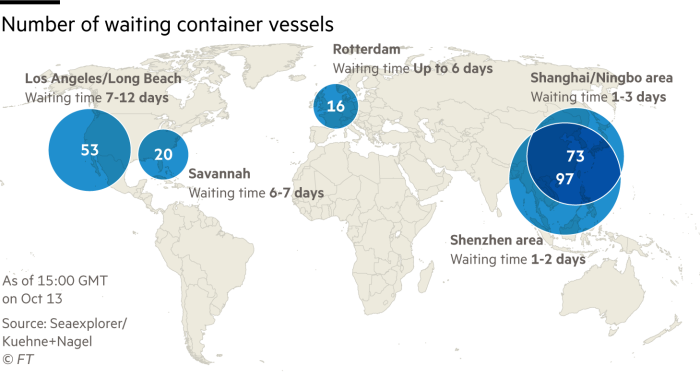

Since then, ships outside the port have continued to be in trouble, with a shortage of truck drivers on land, leading to shortages of inventory and delays in deliveries-as the online shopping boom caused by the pandemic has increased the demand for next-day deliveries, prices have increased and Make consumers feel frustrated.

Analysis shows that productivity gains from automation are inconsistent-sometimes negative

According to John Manners-Bell, the chief executive of the consulting firm Transport Intelligence, in many cases, the lack of automation and outdated labor practices in ports compound the problem. This is especially true in the Los Angeles-Long Beach port complex on the west coast of the United States. In September, 76 ships had to stay at sea waiting to unload, a record. In China, many ports operate around the clock. In contrast, many people in the United States only work 112 hours a week and have rest days.

But analysts say that automation can improve the efficiency and safety of port services, reduce labor costs by 40% to 70%, and reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

The automation of the container terminal began in Rotterdam, the Netherlands in the early 1990s, where they used unmanned portal cranes and automated guided vehicles. According to Roeloffs, there are now nearly 40 partially or fully automated container terminals in operation worldwide.

One of the largest terminal development projects is the Shanghai Yangshan Deepwater Port in eastern China, which opened three years ago and can handle more than 40 million containers each year. It replaces a large group of workers with bridge cranes, automated guided vehicles and rail-mounted gantry cranes-all of which can be driven from a long distance from the control room.

Other Asian countries have followed suit. In Singapore, the Tuas Super Port, which is planned to be opened in phases, will become one of the largest and most automated ports in the world. Its technological innovations include unmanned vehicles, drones, data analysis and unmanned trucks for port transportation. Digital platforms will also be used to reduce port congestion and bureaucracy.

However, although the pandemic highlights the necessity of modernization, it also highlights its limitations.

Manners-Bell said that although China has some of the world’s largest and most modern ports, Beijing’s hardline approach to Covid in terms of labor means that port operations are often closed.

Due to the accumulation of containers waiting to be loaded, ships anchored at anchorages outside major ports such as Ningbo and Yantian, which caused serious land congestion.

In addition, the new technologies that must be acquired in order to save labor costs are still expensive.

A 2019 report by rating agency Moody’s questioned the high capital investment costs required, warning of political risks from uncertain productivity growth, operational disruptions and potential conflicts with unions.

“Many analysis of productivity indicators between automation and traditional terminals shows that the productivity indicators brought by automation are inconsistent, and in many cases, automation has brought negative productivity gains,” Moody’s said.

There is also the question of who should pay for infrastructure improvements, especially if the port is privately owned. For example, in the UK, most ports are owned by private equity, sovereign wealth and offshore fund consortia.

Environmental issues have intensified this debate. This month, the major British port group, the trade association of Britain’s largest port operator, called on the government to set up a special “green port fund” to invest in green infrastructure together with the industry.

Such infrastructure may include charging points for ships in the port and a new generation of electricity and hydrogen-powered equipment that can help the port achieve the British government’s net zero emissions goal.

[ad_2]

Source link