[ad_1]

For small business owners in Glenside in the northern suburbs of Philadelphia, rising prices have become a common gripe.

“It’s really affecting my bottom line,” says Alisa Kleckner, who sells masks and costumes, primarily using leather, for theatre productions. “The cost of raw goods has gone up, the cost of transportation has gone up, and also the entertainment industry is suffering,” she says.

Joe Sparacio, who runs the Crate and Press Juice Bar, is worried about the possible hit to come. “The cost of all our produce went up,” he says, “strawberries, blackberries, almond milk. Chicken went up threefold. For now it’s not a problem because the customers are paying more, but if that stops then it’ll be a big problem.”

The inflationary spike running through the country has injected a lot of uncertainty into the local economy, admits Napoleon Nelson, a Democratic state representative in what is one of America’s most politically contested battleground regions. “It’s more than the usual gas prices,” he says. “We’re not sure how long this will last. It’s a struggle.”

America’s bounceback from the depths of the pandemic has been remarkably vigorous this year, after President Joe Biden approved $1,400 in direct payments to low and middle-income households and vaccinations spurred a quick lifting of restrictions on activity and a burst of spending. US economic growth in the first half of the year averaged 6.4 per cent on an annualised basis, potentially setting the stage for its strongest performance since 1984 — while employment has jumped by 3m since the start of the year.

It is the sort of economic picture that should provide a boost to the party in power and leave the opposition Republicans struggling for political oxygen.

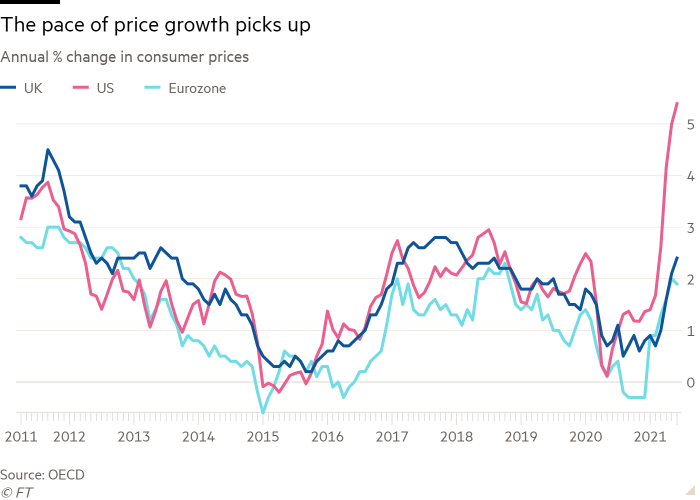

However, the one blot on an otherwise encouraging picture is higher than expected inflation, which has put private sector forecasters, Federal Reserve officials and Biden administration economists on edge.

June data showed the labour department’s consumer price index rising by 5.4 per cent compared with a year earlier, while an alternative measure, the commerce department’s personal consumption expenditure index, increased by 4 per cent over the same period. Core prices, stripping out volatile food and energy, have been somewhat tamer, but are still elevated at 4.5 per cent for the CPI and 3.5 per cent for the PCE. The Fed’s inflation target is 2 per cent, on average.

Many US economists and policymakers believe that over the coming months, as supply chain bottlenecks such as semiconductor shortages ease up and the reopening effect on prices of some goods and services subsides, price pressures will fade away and inflation will fall back. While some prices have soared this year, they are in many instances simply recovering the ground they lost during the pandemic, and may not move much higher.

Even so, the current rise in prices is already emerging as a source of political vulnerability for Democrats and the White House as they try to keep the American public onside and supportive of their sweeping economic agenda ahead of the midterm elections in 2022.

Beyond the $1.9tn stimulus package enacted in March, the US president has backed a $1tn bipartisan infrastructure plan, as well as further spending worth up to $3.5tn to bolster the US social safety net that he is looking to pass solely with Democratic votes.

Republicans sense inflation provides an opening — a chance to label the Biden administration as reckless big spenders and the recovery a short-term sugar-high. Party strategists say the Republicans intend to make the jump in living costs a central message to bludgeon both the White House and congressional Democrats.

“What you have is a president who is looking at bringing an economy back up to speed, which Americans are ready for, and they’re primed for,” says Amy Walter, editor-in-chief of the Cook Political Report, a non-partisan newsletter, in Washington. “But what happens if our current inflationary troubles?.?.?.?turn out to be not so transitory?

“Then it becomes a big challenge for his party in the midterm elections,” she adds, “to defend votes on big spending, big-ticket items.”

Spending plan

When Biden entered the White House in January with his party controlling both chambers of Congress, Democrats wanted to demonstrate to Americans that government spending could help households in very tangible ways, particularly in times of need such as the pandemic.

Many in the party, as well as left-leaning economists, believe that fiscal policy was excessively austere under Barack Obama after the 2008 financial crisis, leading to a sluggish recovery that failed to help the middle class. To avoid repeating the same mistake in 2021, they wanted to achieve a booming, high-pressure economy that would lift wages and help the country return to full employment as rapidly as possible.

Biden’s stimulus plan — which included direct payments as well as expanded unemployment benefits, a subsidy for children, and aid to state and local governments — has stoked a solid rebound and reduced poverty. Yet Republican lawmakers are betting that it will backfire, both economically and politically.

Some Republicans have even harked back to the 1970s stagflation years to paint an alarming picture of the economic environment that will unfold under Biden. Republicans have already started airing ads targeting vulnerable Democrats in swing states and districts on inflation and one party aide tells the FT that high prices are becoming a “continuous message” in their political communications.

“As the product of a single-parent household, I know just how hard this inflation is hurting families trying to make it work on shoestring budgets,” says Rick Scott, the Florida Republican senator who is leading his party’s efforts to win control of the Senate next year.

Although the midterm elections are still 15 months away and could be decided by a wide array of factors, the political battle over Biden’s economic plans — including high inflation — is expected to be fought most intensely in swing districts like those in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Glenside and its surrounding areas helped the Democrats win control of the House of Representatives in 2018 and Biden prevail in the 2020 election against Donald Trump, and Republicans are looking for arguments to gain them back.

“Americans are rightfully concerned about the rising cost of everyday goods. Voters will hold Democrats accountable for their harmful economic policies that are making everything more expensive,” says Matt Berg, a spokesman for the National Republican Campaign Committee, which is charged with winning control of the House from the Democrats next year.

But it is far from clear that the Republican messages will stick. Biden does not appear to be suffering from a backlash on the scale of the Tea Party revolts against Barack Obama’s healthcare reform that dominated his first summer in office in 2009.

According to the Realclearpolitics.com polling average, Biden’s approval ratings have dipped slightly, from 55.5 per cent in late January after inauguration, to 51.3 per cent this year, but remain in a relatively healthy state given the deep divisions and polarisation in the US electorate.

Inflation worries have in recent weeks taken a back seat to the resurgence of the Delta variant of coronavirus in large swaths of the country, which could potentially chill economic activity and cool prices down in the coming weeks and months.

Despite that, Biden has still felt the need to vow vigilance on inflation and acknowledge the struggles of ordinary Americans suddenly facing higher prices for food, petrol, housing and other key expenses.

“My administration understands that if we were to ever experience unchecked inflation over the long term, that would pose real challenges to our economy,” Biden said on July 19. “So while we’re confident that isn’t what we are seeing today, we’re going to remain vigilant about any response that is needed.”

Adjusting wages

High prices do not only provide a target for Republicans, but could weaken Democratic enthusiasm for the White House’s economic agenda. One big worry within the party’s base is that inflation might make housing costs too onerous for low and middle-income families.

They also want to ensure that wages are increasing at least as fast as inflation, to avoid a big loss of purchasing power for households that would undercut the benefits of their stimulus measures and planned expansion of the social safety net.

“Large and unexpected surprise inflation?.?.?.?can reduce real wages — especially if employers do not build cost-of-living adjustments into their wage increases,” warned Jason Furman and Wilson Powell of Harvard University in a paper released on Friday by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Price growth has been more rapid than compensation growth, and so real compensation has been falling.”

Democrats also fret that in this environment the Fed, which has the most powerful weapon to curb inflation — interest rates — might be tempted to tighten policy more quickly than expected in order to stave off higher prices, thereby choking off the recovery before it reaches full employment. Although the Fed is debating a reduction to its $120bn per month asset purchase programme, it has indicated that any increase in interest rates is far in the future, but there is still nervousness among Democrats that the central bank’s patience in keeping policy loose may run thin.

“My concern is that a misplaced diagnosis playing out with inflation could cause the Federal Reserve to prematurely raise rates and constrain wage and employment gains that have been beneficial to millions of Americans,” Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the progressive New York congresswoman, told Jay Powell, the Fed chair, at a hearing of the House financial services committee last month.

The Biden administration has limited options to try to rein in prices on its own if needed. It has already moved to try to address some of the supply chain disruption, particularly in the semiconductor sector, that has driven up the cost of cars and other goods. It has also proposed to overhaul US antitrust policy to crack down much more aggressively on monopolistic behaviour by large corporations. And officials have argued that their additional spending plans on infrastructure, education and the social safety net would be disinflationary — making the economy run more smoothly and equitably.

“If your primary concern right now is inflation, you should be even more enthusiastic about this plan,” Biden said in July.

Research from Moody’s Analytics by Mark Zandi, a former economic adviser to the late Republican senator John McCain’s 2008 presidential race, supported Biden’s view, saying much of the “additional fiscal support being considered is designed to lift the economy’s longer-term growth potential and ease inflation pressures” — including steps to boost housing supply and reduce the cost of prescription drugs.

Joel Benenson, Obama’s pollster and adviser during his 2012 re-election campaign, says the White House and Democrats have some key advantages in the argument over inflation. One is that middle-class Americans are more likely to believe Biden is “working for them every day” compared to “obstructionist” Republican congressional leaders; another is that “traditional, conventional thinking” that higher prices will be a political liability may not apply during a time of great economic and social upheaval due to the pandemic.

But he says Biden may still want to be cautious as he presses ahead with the rest of his economic agenda. “People in the Democratic party will always want to make packages bigger and bigger. Politically, it is smart to know how much the public can tolerate and at the same time be able to accomplish what you need,” says Benenson. “You really don’t want to jeopardise a lot of Democrats in swing districts in the midterms by overshooting the runway.”

Adrienne Elrod, a Democratic strategist and former Biden campaign official, dismisses the notion that the administration’s message was being muddied or derailed by rising inflation. “We’re in a very, very good place economically and those numbers can be improved even more by passing the infrastructure package and the overall Build Back Better agenda,” she says. “I think Republicans are just looking for whatever they can find right now to criticise, because there’s not a whole lot out there to criticise.”

According to a Monmouth University poll released last week, just 5 per cent of American voters listed inflation as their top concern, but a greater share — 11 per cent — was worried about being able to pay their bills.

In Glenside, Philadelphia, local residents — despite their worries about inflation — are generally giving Biden the benefit of the doubt, at least for now. Shannon Dougherty, the owner of a café in the town, says she has been tearing her hair out this year over staff shortages while bemoaning the cost of the chicken wings she serves. But she believes the disruptions will be resolved. “I believe that as the country recovers we will see prices drop and staffing improve,” she adds.

Politically, the battle lines around Biden’s economic agenda are clearly forming over the issue of high prices. Although high inflation has not reared its head for decades in America and has not been a factor politically since the 1970s, it dogged both incumbent presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter during that era, in a worrying precedent for Biden that Republicans will try to replicate.

“Republicans are going to argue that Joe Biden came into office saying he was a moderate. Instead, they just keep spending money we don’t have, it’s driving up inflation, it’s driving up our debt, it’s hurting our grandkids,” says Walter, the political analyst. “You can expect that regardless of what the inflation number actually is”.

[ad_2]

Source link