[ad_1]

When the Dutch government reversed its decision to allow live public events to go ahead this summer, the industry response was swift and uncompromising. Music festival promoter ID&T immediately filed legal action to try to reverse the ban. Since then, more than 40 event organisers in the country have joined the lawsuit.

“For us it was basically a slap in the face,” says Rosanne Janmaat, head of operations at ID&T, speaking after the cancellation of its flagship Mysteryland dance music festival that had sold out of its more than 125,000 tickets — the sixth event the company has been forced to ditch this summer.

“Electronic music is closely linked with Dutch culture, so it feels like something worth fighting for,” says the ID&T executive, adding that the country’s wider events sector — including trade fairs — generates €7.2bn in annual revenues and supports 100,000 jobs. “This is a fight for the future of the industry.”

The event organisers — including those behind the country’s Formula One Grand Prix in September — are challenging the Dutch government’s order to reimpose restrictions on restaurants, bars, cafés, nightclubs and public events. The move followed a more than tenfold increase in the country’s coronavirus cases to about 7,000 a day, which it said had mostly “occurred in nightlife settings and parties with high numbers of people”.

The Dutch U-turn on lifting Covid restrictions and the ensuing legal battle underlines how Europe’s improving economic outlook risks being held back by the spread of the highly infectious coronavirus Delta variant, which started in India and is on track to account for 90 per cent of all of Europe’s new Covid-19 infections by next month.

The recent resurgence of the virus is one of several factors that economists are grappling with as they try to gauge the strength of the eurozone’s expected recovery. Other risks include supply chain bottlenecks snarling up production lines at carmakers and other manufacturers, as well as the danger that Europe’s governments could cut fiscal support too soon and kill off the recovery, just as they did during the bloc’s 2012 debt crisis.

“The post-pandemic boom will subside next year once everyone has done their pent-up spending but by then governments will reduce their fiscal spending,” says Christian Odendahl, the Berlin-based chief economist at the Centre for European Reform think-tank. “This reminds me of 2010 and 2011 when Germany and others switched to austerity too soon.”

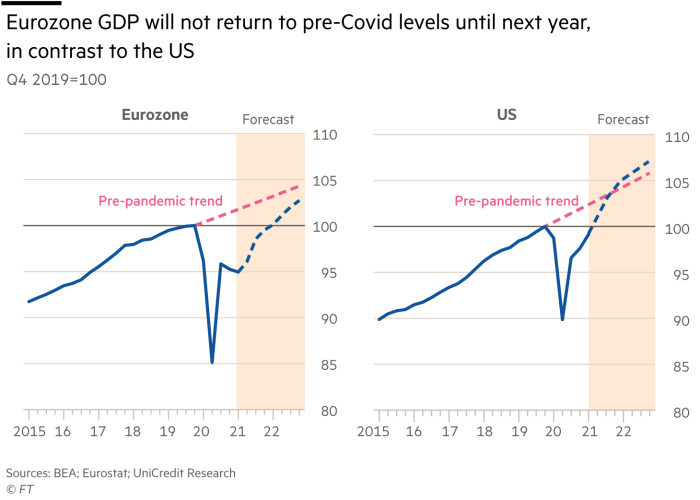

The continent’s growth is already lagging behind the US, which has rebounded to its pre-pandemic level of output almost a year earlier than the eurozone is likely to achieve, fuelled by US president Joe Biden’s multitrillion-dollar stimulus programmes, which economists worry are set to widen the transatlantic gap.

Despite these concerns, most economists remain upbeat about the prospects for the eurozone, which is expected to rebound from its double-dip recession over the winter with solid growth between 1.5 and 2 per cent in the three months to June, when official figures are released on Friday.

The solid growth figures will be read as the latest signal that Europe is firmly on the road to recovery. Boosted by the lifting of lockdowns in April and May, business and consumer confidence has been surging across the continent, while retail sales have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels and the region’s stock markets have climbed to record highs.

Eurozone gross domestic product is widely expected to grow at between 4 and 5 per cent both this year and next, its fastest rate since the single currency was created over two decades ago, as it recovers from a record contraction of 6.6 per cent in 2020.

Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, said last week that the economy of the 19-country bloc “is on track for strong growth in the third quarter”.

But when asked about the rapid spread of the Delta variant, Lagarde said: “We are in the hands of those who are going to take all the necessary precautions to make sure that contagion is not producing the negative economic effects that we have seen in the past.”

Optimism abounds

Coronavirus infections across Europe hit 151 per 100,000 people in the week to July 18, up from just below 90 a week earlier, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. It forecast that the rate could more than double to 373 by August.

In response, governments tightened travel restrictions on arrivals from high-infection countries such as Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands for those people who are not fully vaccinated. Big public events have been cancelled. Nightclubs and bars on the party islands of Ibiza and Mykonos have been shut or told to close early.

The French parliament this week approved a law making Covid-19 vaccination compulsory for healthcare workers, while both Italy and France plan to require people to show a “health pass” to enter public places such as cinemas, restaurants and gymnasiums.

Despite the reintroduction of some restrictions, most economists remain confident that Europe will avoid another round of economically crippling lockdowns, similar to those that dragged the region into two recessions during the past 18 months.

This optimism stems from data showing that hospitalisations in Europe have not increased in line with Covid-19 infection numbers, as many of those catching the virus now are aged in their twenties or thirties and therefore less likely to suffer the most serious symptoms of the virus.

Analysts also take comfort from the recent dip in infection numbers in many countries hit by the Delta variant, particularly the UK, which lifted almost all legal containment measures on July 19.

“The data continue to suggest that vaccinations have weakened the link between infections and medical complications significantly,” says Holger Schmieding, chief economist at German investment bank Berenberg. “No large-scale restrictions will be imposed in Europe.”

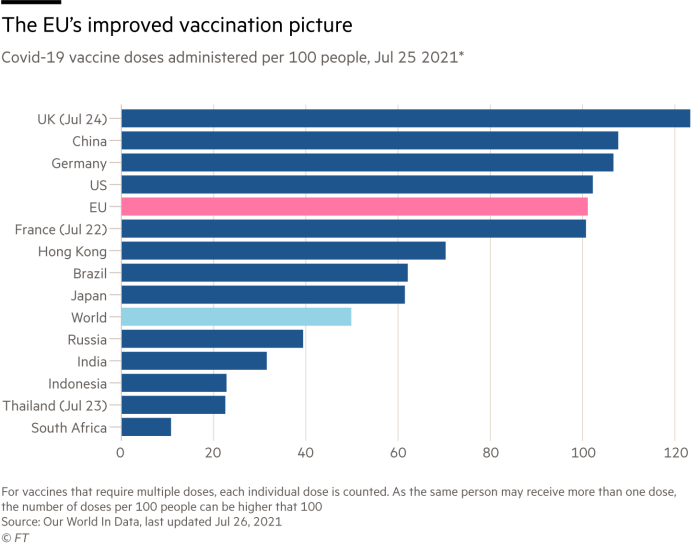

Europe’s vaccination campaign has accelerated after a slow start to provide almost 70 per cent of EU adults with at least one shot, while more than half are now fully vaccinated. Among more vulnerable people aged over 80, more than 83 per cent are fully vaccinated.

“I really don’t think we are going to have shutdowns any more,” says Maria Demertzis, deputy director of Bruegel, the Brussels-based think-tank. “The feeling across Europe is very strong against lockdowns and people’s patience has been exhausted. You might have some localised containment measures or slight restrictions on nightlife, but that’s it.”

The pandemic has left massive pent-up demand among consumers to go back to travelling, eating out and socialising. Businesses are equally desperate for economies to reopen. And unable to spend money on many of their usual activities, eurozone households have built up excess savings beyond what they would normally squirrel away, ranging from about 5 per cent of GDP in Germany to 8.5 per cent in Italy, according to the OECD.

Although economists struggle to estimate how much of this money will be spent or how quickly.

For now, the rapid spread of the Delta variant seems most likely to hit tourism, travel and hospitality, which is bad news for the economies of southern Europe that rely heavily on these sectors. Spain only expects foreign tourist revenues to reach half their pre-pandemic levels this summer, up from a fifth last year. That is a heavy blow for a sector that in 2019 generated 12 per cent of Spanish GDP and 13 per cent of jobs.

This year’s rebound in global trade should have boosted Europe’s export-focused economy with its high current account surplus. But despite this tailwind, eurozone industrial output has undershot expectations and was still languishing below pre-pandemic levels in May.

German manufacturers — in particular the big carmakers — have been struggling to keep up with that rising global demand due to shortages of many materials, including semiconductors, metals, plastics and wood, as well as bottlenecks in container shipping.

“There are two risks — one is the Delta resurgence and the other is the supply constraints,” says Clemens Fuest, president of the Ifo Institute, an economic research group in Munich. He adds that about half of German companies are reporting supply problems, by far the highest level in the 20 years Ifo has been doing its monthly survey of businesses. “Our baseline is that these supply constraints will go away, but we don’t really know.”

‘Europe has learned from its mistakes’

One of the biggest worries after the pandemic sent Europe’s economy into a tailspin last year was that a wave of bankruptcies and job losses would hit the region’s banking system and trigger a repeat of the debt crisis that brought the eurozone to its knees a decade ago.

This has not materialised. Instead, bankruptcy filings in the eurozone fell by a fifth in 2020 and remain below pre-pandemic levels this year. Unemployment in the bloc rose from a low of 7.1 per cent to 8.5 per cent last year, but it has since fallen back below 8 per cent.

The impact of the crisis has been cushioned by strong support from both the ECB, which kept interest rates close to record lows, and governments, which paid the wages of millions of people on furlough schemes, guaranteed loans worth hundreds of billions of euros, suspended insolvency laws and granted moratoriums on debt repayments.

The ECB in July changed its strategy to raise the bar on the level of inflation needed before it will raise interest rates, giving governments more time to keep borrowing on ultra-cheap terms to support the recovery.

“We have to be mindful of not withdrawing business support and waivers on bankruptcies prematurely,” says Olli Rehn, head of Finland’s central bank and an ECB governing council member. “Once we have a strong recovery going, then we should apply Keynesian countercyclical policy and reduce the fiscal stimulus.”

The surge in government spending increased the eurozone’s overall budget deficit to 7.2 per cent of GDP last year and almost 8 per cent this year, according to the IMF — although this is dwarfed by US deficits of almost 15 per cent last year and over 13 per cent in 2021.

Additional firepower to support Europe’s economy is due to start flowing once distribution of the EU’s €800bn Recovery and Resilience Fund begins after the summer, providing grants and cheap loans over five years to support investments in areas such as green energy and digitisation in return for commitments on structural reform.

“Europe has learned from its mistakes,” says Katharina Utermöhl, senior economist at German insurer Allianz. “European fiscal policy has surprised on the upside so far this year and even though we are not talking about the same super-stimulus we have seen in the US, we are now looking at the labour market as a glass half full rather than half empty.”

Some economists warn, however, that Europe could still repeat its 2012 error of killing off the recovery by switching too early to fiscal consolidation.

“The US has already passed [its] pre-pandemic level of GDP,” says Erik Nielsen, chief economist at the Italian bank UniCredit. “By the end of this year they will pass the previous growth path and then they will overshoot it to make up for the shortfall. But in Europe, at best we get back to the earlier trend line by 2024.”

A decisive factor will be what happens to the EU’s fiscal rules limiting the size of budget deficits and debt levels — known as the stability and growth pact. These rules have been suspended since last year and are due to snap back in 2023. That will force most countries to slash their deficits below 3 per cent of GDP and to start bringing their total debt levels down towards 60 per cent of GDP. But the rules are widely seen as unworkable given the scale of borrowing since the pandemic hit, which pushed many countries’ public debts well above 100 per cent of GDP and Italy’s close to 160 per cent.

The European Commission is set to propose a reform of the rules later this year, which seems certain to end in a clash between frugal northern European countries and more heavily indebted Mediterranean states.

“The Germans and the Dutch will try to push the rules as hard as they can, but they have to be eased,” says Vítor Constâncio, former vice-president of the ECB. “The crucial countries to push for reform are France and Italy, given their debt situation after Covid.”

The tone for this debate will be set by elections in Germany in September that will determine both Angela Merkel’s replacement as chancellor and which parties form the next government.

Germany’s own constitutional debt break, which puts strict limits on government borrowing, has also been suspended since last year. Most large parties have committed to reinstating the rules without changes, except for the Greens, which want the debt break changed to allow €500bn to be spent on the transition to a low-carbon economy over the next decade.

The Greens are running in second place in the polls with about 20 per cent support and are widely expected to be part of Germany’s next ruling coalition, fuelling hopes among economists that fiscal policy restrictions could be loosened both in Berlin and across the EU.

“What Germany decides for its own fiscal rules it cannot deny the rest of Europe,” says Odendahl at the CER. “The Greens could open up the debt break for climate spending, which could be a blueprint for what could be achieved at a European level.”

[ad_2]

Source link