[ad_1]

Can a sepia-tone photograph capture hues of identity, longing, nostalgia and home?

Consider this. It is the spring of 1982. Twenty-five-year-old Tahzeeb has just landed in Riyadh after taking her maiden flight from Pakistan to reunite with her husband Nasir who works at the US embassy in Saudi Arabia.

Shortly after she arrives, Nasir has a novel idea, to take a portrait shot of the two of them.

As he sets up the tripod, his eyes trace her silhouette sitting on the ground, mind lost in thought. He wonders if she is thinking about her journey, the family she left behind – a distant identity – to join him in the strangeness of this new place. Home, which was in the streets of East Pakistan, had moved across city, country, and continent, just like that, for them. He kneels to ask her to look at the camera – and that was when the device’s timer went off and captured the duo looking at each other. Pensive, quiet, powerful.

Nearly three decades later, their daughter Israa, 33, a Pakistani-Canadian, looks at this half-faded photograph and wonders about her Baba and Mama’s journey from Pakistan to the Middle East. What did identity, belonging, and home mean for them? She poses this thought to the world – as a postscript to this picture – through the Instagram account Brown History, a veritable ode to artefacts like this photograph.

“A lot of people say that the past doesn’t matter – and perhaps, it doesn’t in many ways,” Israa reflects on what inspired her to share this moment and musing.

“But learning the small details of the lives of your parents or grandparents humanises them … It forces you to look at them like peers almost, people with hopes and dreams, people who struggled, people who loved. It allows you to see your family in a different way … that creates a closeness and empathy that wasn’t there before.”

‘History rewritten by the vanquished’

A compilation of this familiarity and human expression finds home on Brown History, a crowdsourced collective that started in March 2019. Founder Ahsun Zafar, a Canadian national, wanted to humanise history – half-remembered anecdotes, fading family albums, treasured tales – whatever shape or form it bore. More than a thousand submissions and almost two years later, the platform now has a community of more than 488,000 people, all tasked with telling and re-telling lesser-known stories and lives.

“There is a common saying that history is written by the victors. If that is the case, then Brown History is history rewritten by the vanquished,” Ahsun says, echoing the bio of the page.

He is not alone in this mission. Platforms like Daak Vaak and Museum of Material Memory, along with a host of other region and culture-specific social circles, are engaging in a digital tryst with time and memory. They become unwavering lenses into the past, of people and places.

Together, they capitalise on modern storytelling techniques to transform oral history into crowdsourced archives, straddling the translucent line between personal and shared history. Individual stories inherited across generations take the form of reflective narratives and crystallised visuals. Notably, the immersion happens both ways: readers jump through lands and centuries, tracing intricate epochal shifts.

“The idea behind Daak Vaak was to expand our cultural vocabulary to integrate local ideas and references,” founders Prachi Jha and Onaiza Drabu told Al Jazeera. Prachi, 34, hails from New Delhi, India and runs a science education NGO in Geneva; Onaiza, 31, is a digital consultant based out of Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir. They formed an alliance in 2017 to create the newsletter-turned-social-media-platform Daak Vaak (Hindi for Post and Talk) in hopes of preserving and reviving literature and art from the South Asian subcontinent.

“We felt like our education and upbringing had left a huge gap in our understanding of the ideas, people and movements that have shaped the culture of South Asia.” It now has a subscriber list of more than 100,000 people.

Keen to extract impressions from the subcontinent is the Museum of Material Memory, started by school friends Aanchal Malhotra and Navdha Malhotra (they are not related). Both are from New Delhi, and their families are partition survivors who moved to independent India from Pakistan after 1947.

The project is an extension of Aanchal’s book, Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory, which outlines the stories behind intimate objects carried by refugees of the partition. The idea mutated into a digital platform as a response to the overwhelming interest, prompting her to collaborate with Navdha and craft a space dedicated to matter and meaning.

“People from across the subcontinent – and from the diaspora across the border – could submit stories about the objects that have existed in their families for generations, and we can all celebrate our historical materiality, no matter how mundane it might be,” they say. The result is a repository of emotionally and historically charged artefacts dated until the 1970s.

A bridge to the past

When Anviti Suri, based in Nagpur, India, first came across the Museum of Material Memory, she felt a powerful urge to contribute something. Her quest unfolded as follows: she asked around in her family about old objects with interesting historical connections; her grandmother quenched this curiosity by telling her about a beautiful golden necklace she inherited from her mother.

“There’s something about the process of talking about an object that brings up details that wouldn’t come up otherwise. All the events and stories associated with the object come up, and not just one singular event,” she muses reflectively, referring to the history the necklace had borne witness to. Anviti’s grandmother received it at the age of 12 when she was getting married. This was a time when India and Pakistan were still one, and both of Anviti’s grandparents can trace their families to areas that are now on the Pakistani side of the border. “I grew up on stories of the Partition,” Anviti says. She went on to contribute another story for the page, one about a pistol manufactured in 1903 that her grandfather bought from a police officer.

Her desire to contribute to the platform was simple: It gave her a sense of pride. “We did not have any documentation of what the family had been through, where they came from. So writing this piece gave me an opportunity to start building a family archive of sorts.”

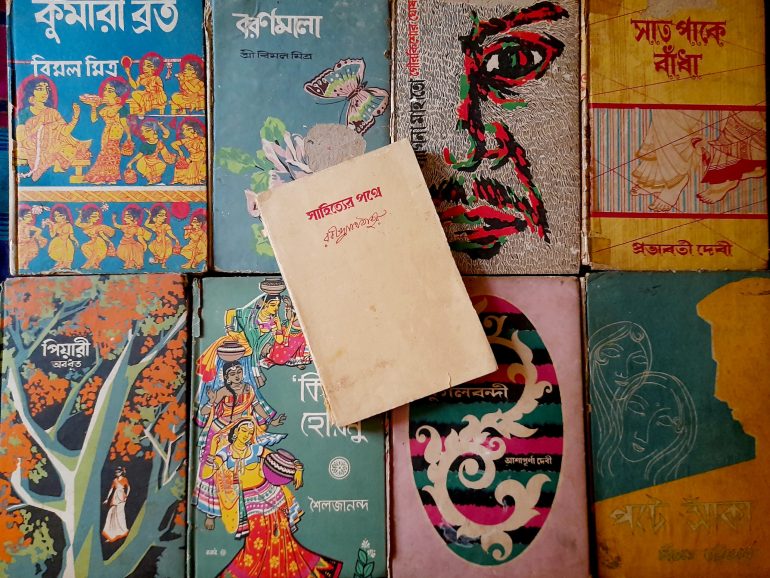

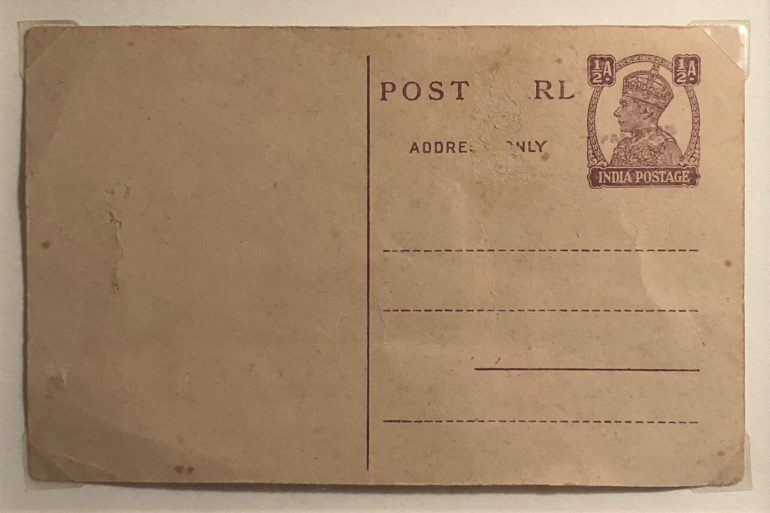

Other objects that found a home on the platform include a postcard from 1947 with a stamp of a newly-carved Pakistan, frayed books with notes in the margin, brass crockery passed on as heirlooms, souvenirs from World War I trenches in the shape of wooden boxes. All resound with human emotion and social condition.

“Material memory in itself works in mysterious ways,” Aanchal and Navdha explain. “We surround ourselves with things and put parts of ourselves in them. It hides in the folds of clothes, among old records, inside boxes of inherited jewellery, between the yellowing pages of old books, in the cracks of furniture and the stitches of frayed, embroidered handkerchiefs. It merges into our surroundings, it seeps into our years, it remains quiet, accumulating the past like layers of dust, and manifests itself in the most unlikely scenarios, generations later.”

“The Museum focuses not on capital H histories, but small h histories – oral histories, quiet histories. Those that require interviewing family and loved ones, or introspection of an intimate nature.”

How memory trickles through generations is a reminder of what has been lost, but also what remains. When Hiam Amani, an American with Bangladeshi ancestry, found an old photo of her aunt, a freedom fighter during Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971, she thought it would make a good addition to Brown History’s page. She had heard the stories before: her aunt was a student at Dhaka University, had become a political leader, spent a lifetime advocating for the preservation of Bangladeshi culture, and witnessed the birth of Bangladesh. Some 40 years later, Hiam called her aunt to hear more about the picture before submitting it to Brown History.

“This conversation was the first time as an adult that I truly got to hear the details and understand this history that is so significant to the birth of Bangladesh … She spoke on the injustices and inequality and the struggle of feeling like an outsider in your own country at the time.” Hearing these stories more than a learning exercise, it was a front-row seat to watching people live their stories and taking note of how legacies shape up. Hiam saw in the picture a reflection of her aunt, her nation’s history, and herself. Nothing could feel that powerful.

For Hiam, this was a chance to reconnect with her aunt, as well as the culture and heritage she had only heard about. A couple of weeks after her conversation, Hiam’s aunt passed away. “Her death was completely sudden and unexpected and I am forever grateful to Brown History for not only highlighting my family’s history, but preserving it.”

An exploration of the present

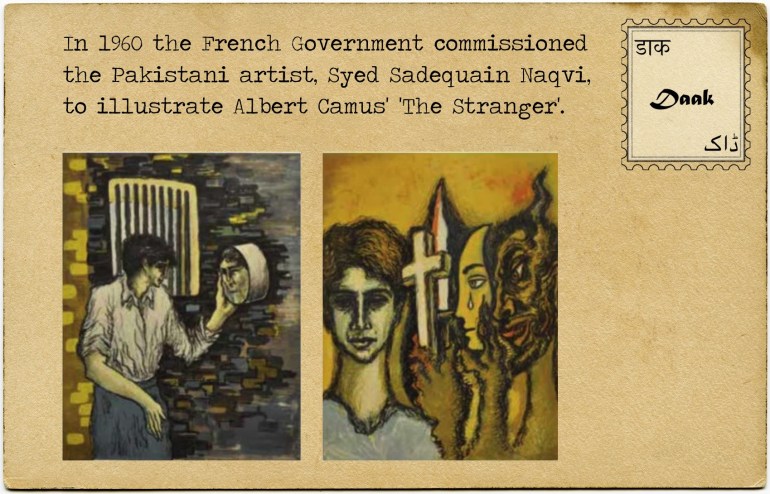

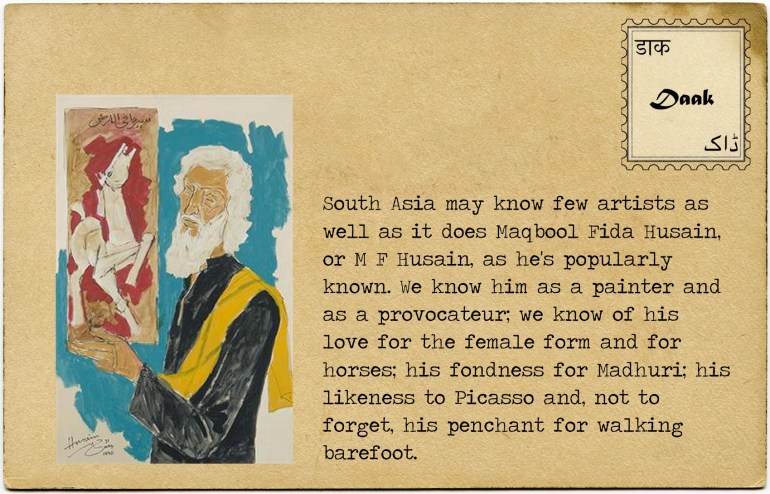

A similar exercise in exploration is arduously materialising at Daak Vaak, where relatively unknown or forgotten pieces of literature, artwork and ideas are shared every Sunday in the form of digital postcards. The imagery is faithful to that of a real postcard: a characteristic ochre palate descending on a crinkled landscape sheet, bearing a stamp on the top right corner ready to land in mailboxes.

While Daak Vaak started as a newsletter and not an archive, Prachi and Onaiza recall, almost four years of weekly posts have transformed it into one carrying obscure literature and art sourced from the subcontinent.

In July 2020, Ravleen, a regular visitor to the page, found storied Indian novelist and poet Amrita Pritam’s poem, Mera Pata. The poem left her with a curious feeling: how accessible is Punjabi literature (of which Pritam is a stalwart)?

The next Daak (post) brought a portrait linked to Assamese poetry. “It made me think about the representation of Indigenous and Indian writers in the mainstream.” Daak Vaak for her became a treasure trove of lost literature.

“It’s surprising and sad that I had never explored them enough,” she says. The vacuum sparked something in her, prompting her to translate Punjabi literature to English and submit it to platforms like Daak Vaak itself.

“It felt like something that needed to be done. These poems are beautiful and need to be read by more people.”

Other fragments of cultural wisdom in Daak Vaak’s repository look something like this: intimate portrayals of Indian self-taught cartoonist Mario Miranda, making of literary doyen Rabindranath Tagore’s oeuvre, capturing the friendship and animosity between literary stalwarts Ismat Chughtai and Manto through lost essays. It is textured life that slipped through the cracks of time and mortality, now revived with rigorous research. Prachi and Onaiza hope that people see this as “an archive or repository of South Asian culture and a testament and homage to our shared cultural heritage.”

A community-in-making

Images and posts on these platforms often prompt conversations about identity and roots. Last year, Australia-based Jessica Grover was scrolling through Instagram when she came across a picture of an “Om” tattoo on a gentleman her grandfather’s age; the tattoo struck her because she had grown up looking at it on her grandfather’s wrist too. Serendipitously, the last name of the person who posted the image was the same as hers: it turns out, the person was her distant cousin, the two shared a great-great-grandparent.

“His granddad and mine were from the same part of Punjab which now resides in Pakistan. The family lost touch after the separation of India and Pakistan,” she says. Jessica recalls the excitement in her grandfather’s voice when she told him about this discovery; this was his cousin he played with as a child, with whom he had had no contact for nearly 65 years.

“It’s almost like a window into a different time and seeing how things were. Especially if the particular story speaks to you personally or is a part of your own history, the experience of finding something like it is unparalleled.”

Founder Ahsun nods in agreement and says this is not a rare occurrence. He recalls a photo shared some time ago about a young man’s grandfather surviving Partition. Another woman, recognising the last name of the contributor and the name of the village, realised that he was her grandfather’s cousin with whom he had lost contact because of Partition.

“Brown History is more of a community. It is a bustling place full of energy and wonder,” Ahsun says.

At other times, communities do what is intrinsic to their nature: support and uplift. The founders of Daak Vaak note how users often engage with prompts posted on the platform or send each other poetry. The readers also valiantly take on trolls. “Trolls in comments, luckily enough, we don’t have to deal with, because our readers get there first,” they say jokingly.

Anything viewed from the prism of memory, they all note, will be multidimensional and manifold in representations. When Israa submitted the photograph of her parents, she wasn’t seeking a tangible return. But there was an awareness that deep within her story, and that of others, live spaces where man-made borders dissolve.

“Every family has a story, and that’s the thread that binds us. We all carry similar stories within us, and especially when it’s traumatic, we think we’re alone in that,” she explains.

Israa knows of the Museum of Material Memory and finds this idea well resonated in their digital archive.

“When stories about domestic violence or immigration, or Partition-related traumas, or love, are shared – people see themselves in them. That’s the power of community, of feeling like you’re part of a larger narrative.”

A modern way of storytelling

Platforms like these are increasingly occupying the internet, symbolising the very purpose of their creation: that history, personal and shared, is multidimensional. It is an unspoken but concerted movement to democratise history and share narratives ageing on the sidelines.

Their appeal was organic: through word of mouth, social media sharing, random bouts of scrolling. Ahsun recalls how Brown History once got a shoutout from actor Riz Ahmed. The culture of remembering then flew wide open; reeling in volleys of identities, formats, substance.

But these platforms are more than their subscribers, comments, likes, or any metrics. Social media, as the powerhouse of this movement, does plenty to revolutionise cultural legacy. The advantages are apparent: it is accessible, inclusive, engaging and immediate in its appeal.

It not only offers uninhibited access to diverse stories, Navdha Malhotra explains, but also tacitly extends ownership to the contributor in telling their personal story, and thereby carving a place for themselves in history.

“The immediate shareability also augments our borderless approach, wherein an object in a home in Pakistan can be read about and viewed in homes in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, or even the diaspora. This almost always leads to more stories being unearthed. For our writers, there is also a sense of ownership when the story is published.”

Brown History’s Ahsun concurs. “Thanks to social media, regular people can tell their history from their perspective and their stories and cultures are no longer bound by gatekeepers.” Brick and mortar museums exist as analogue platforms, controlled by a small group of people, giving them a lot of control to decide what is on display and to present the exhibits in their own way. Social media, on the other hand, is free of these constrictions.

With this thought, the moral ambiguity of who gets to tell their stories withers away, leaving behind an unequivocal answer: the people themselves. This also allows platforms to bring about the nuances and complexity of communities, ethnicities, and nationalities instead of compressing them into reductive packages.

“The notion that there are people who are ‘voiceless’ is wrong,” Ravleen notes. “Everyone has a voice, and I hope this platform can help amplify it,” she says of Daak Vaak.

As faithful a friend the internet has been to them, the pitfalls of a booming internet presence are fairly conspicuous.

If history is layered, can anyone fully, faithfully communicate the complexity within each story? “History is so complex and layered, especially in South Asia,” Ahsun notes. “I think my biggest challenge is that my path to knowledge requires me to make mistakes and to be able to grow from them. However, the internet isn’t always the most forgiving place and with more eyes on my posts comes a greater fear of making mistakes.”

Even a well-rounded story has a defined radius that leaves behind tricky terrain. All of these converge into instances of social media backlash, questioning versions and interpretations of the past, and calling the veracity of memory into question.

Other concerns about privilege and luxury do not go unnoticed – intricately tied with these are metrics of authenticity and representation. “We realise that accessing a digital museum definitely comes with its own socioeconomic challenges,” the founders say. “Having access to objects, the time and luxury to document the personal history and accessing digital platforms itself is very much a privilege in Indian society.”

While these considerations have the potential to leave them fazed, each experience shapes a better response.

“I often try to evaluate how people of different castes, religions, politics, class and genders would view the topic at hand and how I can relay the information as correctly as possible. It’s definitely not always well received, but there will always be controversial topics and I have to learn to be comfortable with that,” Ahsun says.

Another way is to be accepting of this fallacy and capitalise on the growing community of readers to help them straddle this grey area. Prachi and Onaiza often resort to this, relying on readers to point out oversights of privilege or simplistic treatment. They often put out calls to readers to suggest literature in languages they may not be familiar with. They do not want to succumb to the “bias of finding and curating that which is familiar”.

“We don’t claim to be experts in South Asian history or culture and we’re as much consumers of this content as we’re producers. We’re learning as we go and make mistakes as well,” they submit while pondering the excesses of the very platform that gives them power.

Stories that move and teach

There are obvious questions in this exercise of history collection. What qualifies as an archive? What should be included?

For the founders at Daak Vaak, the formula seems to be to select stories that echo universal human experiences such as nostalgia for childhood or unrequited love, and some that are unique and come bearing fresh perspective. The submissions so far, Prachi and Onaiza say, would make for an interesting read by any cultural analyst.

Brown History’s Ahsun also ventures an answer, and notes: “The stories that make it through typically either move people or teach people.”

The reliance on memory undergirds the very nature of oral history, Navdha and Aanchal note. “We try our best to support our stories with fact and archival research, but there are some things that remain truths only because of the way in which people remember them, and we celebrate that.”

Author Manu S Pillai believes memory projects cannot replace the work of a historian or other official ways of record-keeping – these posts cannot be subjected to scholarly analysis as one would like. “Research and analysis is still heavy business,” he tells Danish Raza of the Hindustan Times, “but social media helps generate an appetite for history beyond scholarly circles, and any such mass interest is, in the long run, a positive development.”

Pillai’s argument brings up an interesting distinction between history and memory. Katja Müller, a German researcher, argues that real memory is alive and pliable. “Memory is by nature multiple and yet specific; collective, plural, and yet individual. History, on the other hand, belongs to everyone and to no one,” she writes in her paper, Between Lived and Archived Memory: How Digital Archives Can Tell History. Memory takes root through objects and images, while history is an organised and constructed past.

Digital archives that shape memory, she says, can change the way we engage with history.

Reframing identity and expression for the future

Combined, the number of followers on all three platforms easily crosses a million people – which is a million people who can attest to the positive impact digital memory initiatives have.

“Brown people and their voices are extremely underrepresented, we have very few outlets to have our stories be shown and heard,” Hiam says. “Platforms like this are key to preserving social and cultural memory in a raw and unfiltered way.”

“The internet is forever, and these images will live on this page forever.”

The question of sustaining these platforms is hard to overlook. The ingenuity and agility at their core force them to constantly adapt, but do they wonder if obsolescence is on the horizon?

“We don’t worry about it but we definitely plan for it,” Prachi and Onaiza say. “We don’t think it’s wise to completely rely on any one digital platform. So, while we enjoy the engagement and reach of social media, we are diligent in curating and archiving our weekly newsletters.” They refer to the digital postcards that land in mailboxes every Sunday – also hinting at the success the newsletter format has enjoyed during the pandemic.

In the early days, one of their preoccupations was with content saturation, if the knowledge well might drip dry. But time, experience, and social interaction have taught them otherwise. “We’ve learned in the last three years that there is so much to uncover and we’ve barely scratched the surface.”

Submissions to the Museum echo this observation: the archive they are building reveals not just a history of objects and the people they belong to but, in parallel, unfolds generational narratives about traditions, culture, customs, habits, language, society, geography and history of the vast Indian subcontinent.

The founders hope to add to archival histories, augment knowledge and add diversity from the very grassroots. They plan to build a team of curators as they expand, holding exhibitions, and even monetarily compensate contributors.

“Our true hope in encouraging people – in the subcontinent and across the diaspora – to search for items in their homes and archiving the stories of objects as mundane as utensils and books, to as monetarily valuable as jewellery and wedding costumes,” they say. In doing so, they are creating an organic, accessible, digital archive of material culture that showcases the diversity and vibrancy of a vast landscape.

Ahsun also hopes that it proves to be an enlightening experience for anyone who looks at it. Particularly for South Asian people, he hopes that it plays a role in making sense of their identity. “If it’s a person of South Asian descent, then I hope they look at it as a kind of mirror,” he says.

Could history single out platforms like his as windows onto human expression and a prism of social and cultural change? Perhaps, as they carry stories that are at once powerful and fragile, simple and intricate, pensive yet uplifting. There are dualities that make up these communities and platforms – and it is in this that thousands find a home.

Such was Israa’s experience too.

“It’s amazing to think that I am 33 years old but have no idea how or why my grandparents ended up in East Pakistan (current day Bangladesh). What were the circumstances? Why did they decide that? And that is the impact of these platforms – it reflects the questions of identity, history, and belonging back onto the reader.”

[ad_2]

Source link